◄►◄❌►▲ ▼▲▼ • BNext New CommentNext New ReplyRead More

“If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle.”

― Sun Tzu, The Art of War

“Supreme excellence consists in breaking the enemy’s resistance without fighting. ”

― Sun Tzu, The Art of War

“Diplomacy is the art of convincing others to do what you want them to do because the others realized that it is in their interest to do so. ”

― Chas Freeman

The U.S.–China conundrum has been ongoing for decades and is likely to continue for the foreseeable future. As China rises and the gap in strength between the two countries narrows, the U.S. has found it increasingly difficult to deal with a nation that is rapidly becoming its peer. The U.S. has identified China as a security threat, and successive administrations have implemented policies in response, such as Obama’s Pivot to Asia and Biden’s revival of the Quad, among others.

Beyond standard governmental policies, the U.S. has also used various agencies to create problems for China, citing issues such as human rights violations, oppression of Tibetans, and alleged genocide, the 2019 Hong Kong Color Revolution, and accusations of slave labor and genocide in Xinjiang. Unsurprisingly, none of these initiatives have achieved the results the U.S. had hoped for.

For example, the U.S. has accused China of committing genocide against Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang. But have these accusations led to any deterioration in China’s ties with Muslim-majority nations? It doesn’t appear so—I certainly couldn’t find any. Far from being a passive defendant, the Chinese government has taken the opportunity to invite delegations from various Muslim countries to visit Xinjiang and see the region for themselves, contrasting the on-the-ground reality with the narrative presented by the West. The result? Not a single Muslim country has endorsed the West’s accusations. Quite the contrary, China’s clout among the Muslim nations has only increased. The detente between Saudi Arabia and Iran, sponsored by China’s diplomatic effort, is a testimony to this fact.

What about the Uyghurs? Has this campaign turned the Uyghur population against the Chinese government? Not at all. Due to the slave labor allegations, it has become more difficult to sell Xinjiang cotton internationally, and many factories have become reluctant to hire Uyghur workers to avoid unnecessary scrutiny. Ironically, all this has accomplished is fostering resentment among Uyghurs, not toward the Chinese government, but toward the West, and rightly so.

What about the Han Chinese? Anyone paying attention to the Chinese netizens can see that many Han Chinese also resent the U.S. and are defensive of their government over this issue. They know the accusations are fabricated and are disgusted that Western organizations make up lies to smear their country. While the U.S. may claim that its criticisms are directed at the Chinese government rather than the Chinese people, no Chinese citizens make that distinction. From their perspective, an attack on their government, especially on something as serious as genocide, is an attack on the nation and its people as a whole. The Chinese reaction is not unlike the saying of an Arab proverb: I, against my brothers. My brothers and I are against my cousins. My brothers I and my cousins are against the world. Americans should recall that right after the 911 attack, George W. Bush’s approval rating shot up to over 90%, not because Bush suddenly became hugely popular, but because in the face of an external threat, the American people rallied behind their president. Chinese people are no different than their American counterparts in this respect.

In other words, the accusations have resulted in the exact opposite the U.S. had set out to achieve, creating resentment of the Chinese (both the Han and the Uyghur) against the U.S.

As for the 2019 Hong Kong Color Revolution—engineered by the U.S.[1]There is now a popular belief among younger generations that what happened in June 1989 was a CIA-engineered color revolution. It was not—at least not in the beginning. The way it unfolded was entirely indigenous and organic.

U.S. foreign policy toward a country can swing wildly like a pendulum, depending on the political expediency of the moment. Exhibit A: Iraq. When Saddam Hussein invaded Iran, the U.S. supported Iraq by providing satellite imagery of Iranian troop positions. A few years later, when the same Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, he suddenly became U.S. public enemy number one.

In 1989, the Cold War was still in full force, and the U.S. and China were in a period of détente. The Soviet Union would dissolve two years later, but no one could have predicted that at the time. In fact, the U.S. Seventh Fleet was patrolling the East and South China Seas with China’s blessing, as a counter to Soviet aggression. The CIA operated a radar station in Xinjiang to monitor Soviet activity in western China, and a U.S. defense contractor was helping China modernize the radar system on its J-8 fighter jet.

At that time, the U.S. was more worried about China being too weak than too strong. It had no reason to destabilize China.—the result has been equally grim. As many may know, a significant portion of Hong Kong’s population consists of first- or second-generation Chinese who fled the mainland after the Communist takeover in 1949. Politically, this demographic has generally held a favorable view of the U.S. and a deep-rooted resentment toward the Communist government in Beijing. The genius in Washington who came up with the idea of orchestrating a color revolution in Hong Kong likely believed this demographic could be exploited to create unrest and embarrass the Beijing government. They probably anticipated that the Hong Kong authorities would respond with violent suppression, thereby opening the door for U.S. intervention or at least a stronger international backlash against Beijing. But instead, the U.S. managed to alienate a group of people who had traditionally leaned pro-American. For those unfamiliar with the events, the U.S. supported young political activists who stirred up civil unrest. Think of them as the Antifa equivalent in the U.S.—except far more violent and unrestrained.

These activists engaged in disruptive and dangerous acts: occupying major roads to block traffic, vandalizing public property, digging up bricks to throw at police, stabbing random bystanders, and even setting people on fire. The protests paralyzed the city for months. Despite this, the Hong Kong government showed remarkable restraint and tolerance throughout the unrest. The violent government crackdown that U.S. strategists may have hoped for never materialized. Instead, the prolonged chaos gradually eroded public sympathy, even among Hong Kong citizens who were initially supportive of the protesters’ cause. They might not be fond of the CCP, but they certainly abhor the chaos and lawlessness caused by the unrest. Conspiracy-minded Hong Kong people may surmise that some of the rioters are Communist infiltrators engaged in abhorrent behavior to scuttle the movement, whether it is true or false is ultimately immaterial. Eventually, the Hong Kong government passed legislation to restore order and arrested many of the movement’s leaders. Ironically, Beijing today holds a far tighter grip on Hong Kong than it likely would have had the failed color revolution never occurred. Once again, the U.S. achieved the exact opposite of what it had intended, creating resentment of the Hong Kong people against the US and a Hong Kong where its citizens now learned to be far more circumspect in their speech and act because of the newly passed security law, thanks to the U.S.[2]In terms of freedom, the freest period in Hong Kong was the first decade and a half following the British handover to China. During that time, despite portrayals to the contrary in much of the Western media, Hong Kong enjoyed greater civil liberties than it had under British rule. Specifically, there were actions people could take post-handover that would not have been permitted under colonial governance. For example, after the handover, banners calling for the downfall of the Chinese Communist Party could be seen hanging in some of the busiest districts in downtown Hong Kong—something that certainly would not have been allowed during British rule.

Understandably, the British were sensitive to anti-colonial sentiment in Hong Kong, but they also suppressed anti-Chinese Communist Party activism. The colonial administration preferred Hong Kong society to remain apolitical. Moreover, British-ruled Hong Kong was not a democracy. Conversely, there was nothing people were allowed to do under British rule that they could not also do in the early years after the handover.

Following the handover, Hong Kong adopted a representative form of government, with elections contested by political parties that reflected a range of viewpoints—some leaning pro-Beijing, others leaning anti-Beijing. However, after the 2019 unrest, Hong Kong enacted a national security law that significantly restricted civil liberties and effectively marginalized or outlawed political parties and activists viewed by Beijing as troublesome.

American politicians may feel good about condemning China on human rights issues or accusing it of invading Tibet, deluding themselves into thinking they’re embarrassing Beijing. But their ignorance and self-righteousness aside, unbeknownst to them, they’ve only played directly into the hands of the Chinese Communist Party. I can say with absolute confidence that none of these accusations resonate with the Chinese public. If anything, they’ve only fueled resentment among ordinary Chinese citizens toward the United States.

What’s most frustrating is that the U.S. has strong and effective cards it could play, and the US does have substantial political capital it can spend on China. The problem is, they are completely oblivious to them. I will expound on those in the latter part of this article.

Let me return to the epigraph of this article. Sun Tzu’s admonition about the consequences of not knowing your rival could not be more apt here. The Americans do not understand China. They are, quite frankly, clueless—and this lack of understanding has led to policies that are tactless, ineffective, and often counterproductive.

Culturally, Americans are predisposed to be phobic of communism[3]China’s economy is no longer communist; it is arguably more capitalistic than that of the United States. However, in terms of geopolitical narrative, it remains, for all practical purposes, a Communist country.. The very idea of a powerful communist country standing as a peer to the United States is profoundly unsettling to many. If the U.S. could have its way, it would likely pursue regime change in China without hesitation. The only problem is—it doesn’t know how. The U.S. did attempt regime change in Hong Kong, but it’s evident that its level of sophistication is comparable to that of a kindergarten student.

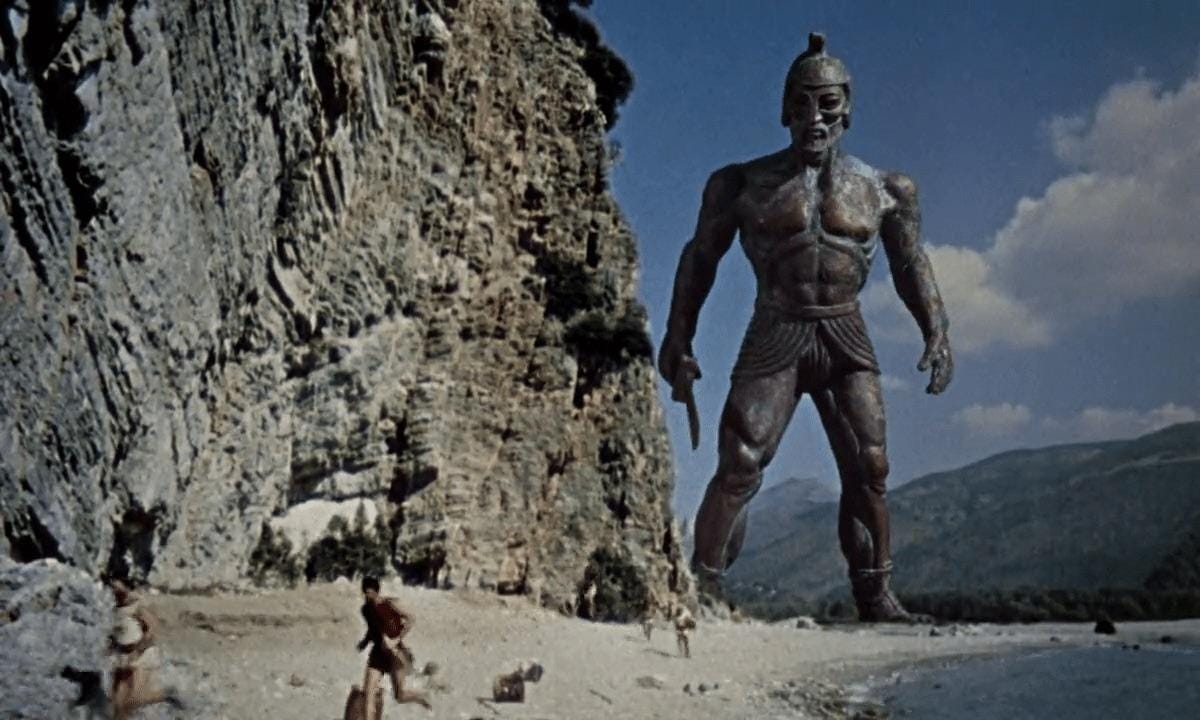

The U.S. has tried nearly every tool in its foreign policy toolbox, from engagement and trade deals to strategic containment, military posturing, and technological restrictions. None of them has produced the desired effect. But is China truly as invulnerable as it appears? Not at all. The People’s Republic of China has its vulnerabilities. I would liken China to Talos, the bronze giant of Greek mythology. To the Argonauts, Talos seemed undefeatable—until Jason discovered his weakness. With a single well-placed strike, Talos fell without a fight. Metaphorically, the PRC is like Talos: it appears unassailable, but only to those who don’t understand where to strike. Without that knowledge, all efforts are wasted; with it, even giants can fall.

In order to successfully induce regime change in China, Americans must first let go of many long-held convictions about the country—and commit to relearning both China and its people. To be direct and avoid any misinterpretation, I will simply list, in no particular order, a series of facts about China as they actually are. Only by developing a genuine appreciation for these realities—not fantasies or projections—and by grasping some of the nuances of the Chinese worldview, can one hope to implement a strategy that might actually be effective. Be warned: due to years of ideological conditioning, some readers may find the facts listed here uncomfortable, even offensive, or challenging to their most deeply held beliefs.

- Tibet is a part of China.

- Taiwan is a part of China.

- The Chinese people do not hate or harbor any ill will toward Americans.

- There is no religious oppression in China; Tibetans and Uyghurs are not oppressed[4]China and its Ethnic Policies, nor have they been subjected to genocide[5]Is the genocide figure of 1.2 million reliable?.

- Chinese people have no desire to rule the world or to see their country become a global hegemon.

In the Chinese worldview, there is no promised land—or rather, their country is the promised land. However, they view their nation’s history as cyclical, marked by alternating periods of unification and disintegration—alongside the enduring concept of “One China.”

One China

People familiar with the dynamics of U.S.–China relations may occasionally encounter the term “One China.” When President Nixon first visited China in 1972, the two countries issued a joint statement known as the Shanghai Communiqué[6]The Shanghai Communique. In it, each side articulated its position on matters of concern. The Chinese side prominently emphasized its stance on “One China,” underscoring how paramount the concept is to the Chinese Communist leadership.

Meanwhile, the U.S. side offered the following as its counterpart:

“The United States acknowledges that all Chinese on either side of the Taiwan Strait maintain there is but one China and that Taiwan is a part of China.”

This statement is now widely misinterpreted by those who overlook the nuance of the document, mistakenly believing that Nixon acknowledged Taiwan as a part of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). That interpretation is incorrect.

The Shanghai Communiqué was a carefully negotiated document, crafted by experts on both sides, with every word meticulously scrutinized. At the time, the United States had no diplomatic relations with the PRC. As far as the U.S. government was concerned, “China” referred to the polity of the Republic of China (ROC), whose central government was seated in Taipei. The implication, then, is that the U.S. statement could also be interpreted as asserting that the mainland is part of the Republic of China, rather than acknowledging Taiwan as part of the PRC.

In other words, by using the word “China” instead of the official names—“People’s Republic of China” or “Republic of China”—the United States created enough ambiguity for both sides to present their respective positions without directly contradicting one another.

Although the Chinese are not generally considered a religious people, the sentiment surrounding “One China” evokes an emotional intensity that, in some ways, mirrors how people in the West speak of God. This attachment is deeply rooted in how the Chinese view their dynastic history, which stretches back over two thousand years.

The classic novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms famously opens with the line:

“The empire, long divided, must unite; long united, must divide. Thus it has ever been.”

Indeed. Ever since the Qin Dynasty unified China in 221 BCE by conquering the six other warring states, it became a fundamental political and cultural principle that no legitimate Chinese ruler could tolerate the existence of another competing polity “under heaven.” Where European statecraft developed the concept of a balance of power, China has had “One China.”

While multiple kingdoms have coexisted during periods of fragmentation, it was always expected that they would eventually battle for supremacy until one emerged victorious, reunifying the land and winning the “great achievement” that would earn the praise of future historians. Even though the imperial dynastic era ended with the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911, the notion of a sole, legitimate governing entity for all of China continues to exert a powerful influence over Chinese politics. This is the root of China’s obsession with the “One China” principle. It is not merely rhetorical—it has substantive consequences for China’s foreign policy, a nuance often underappreciated by outsiders.

For example, Taiwan today maintains diplomatic relations with only a small number of countries. This is because China requires any country seeking formal diplomatic ties with it to first sever official relations with Taiwan. To recognize both the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Republic of China (ROC) simultaneously would imply the existence of “two Chinas”—a concept viewed in Beijing as intolerable.

As a result, Taiwan does not have formal diplomatic relations with the United States, despite the fact that its unofficial relationship with the U.S. is far more substantive than the term “unofficial” might suggest.

It’s worth noting that this diplomatic rigidity is largely unique to China’s situation. Other countries involved in unresolved civil conflicts do not impose such constraints. For instance, both North and South Korea maintain diplomatic relations with Malaysia. Similarly, both East and West Germany (prior to reunification) were members of the United Nations at the same time—as are North and South Korea today.

By contrast, the Republic of China (Taiwan), one of the five founding members of the United Nations, lost its seat in 1971 to the People’s Republic of China. This change occurred because allowing both the PRC and ROC to hold UN membership simultaneously would have violated the sanctity of the “One China” principle.

Here’s another example of how the concept of “One China” can manifest in counterintuitive ways.

Conventional wisdom might suggest that if people in Taiwan advocate for an independent Taiwan with its territory confined to the island itself, it would be less confrontational than asserting that the Republic of China includes both Taiwan and the mainland. After all, the former doesn’t claim land on the mainland. But to mainland Chinese, the former is far more provocative. Why?

Because the latter—even if it is seen as unrealistic—is rooted in the idea of eventual unification under a single China. The former, by contrast, implies the permanent coexistence of two separate polities. That is, it implies two Chinas.

Again, the reason for this visceral response lies in the deeply held belief in “One China.” The concept transcends politics; it touches on identity, history, and legitimacy.

It should also be noted that if the Chinese Civil War had ended with the two parties on opposite sides of the Taiwan Strait, but with the Nationalists holding the mainland and the Communists retreating to Taiwan, the reaction would likely have been the same. Whether ruled by Nationalists or Communists, the governing entity on the mainland would have still rejected the idea of “two Chinas.” The reason? The concept of “One China.”

The Current State of Affairs

The present geopolitical situation in the Sinosphere remains frozen in an unresolved civil war between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on the mainland and the Republic of China (ROC) on Taiwan—a division that has persisted since 1949. In the Chinese historical context, today’s China is seen as being in a “divided stage,” much like the opening lines of the novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms, and thus is expected to eventually reunify.

Although active hostilities ceased decades ago, a political resolution remains elusive. Taiwan has since evolved into a full-fledged democracy with multiple political parties, which has added complexity to internal discourse about how to engage with the mainland and define its own identity.

From the mainland Chinese perspective, the geopolitical situation is relatively straightforward: they believe they have won the civil war and thus possess the “Mandate of Heaven.” Therefore, in their view, the only acceptable future is for Taiwan to incorporate itself into the PRC—even though the PRC has never exercised sovereignty over the island.

By contrast, perspectives within Taiwan are far more diverse.

Those aligned with the Nationalist (Kuomintang) camp maintain that the Communists have not succeeded in usurping the legitimate polity of the Republic of China, and that the ROC remains the only lawful government of both mainland China and Taiwan. This position is in line with the ROC Constitution, which explicitly asserts that its territory encompasses both sides of the Taiwan Strait. This has remained the official position of successive ROC governments, regardless of party affiliation.

Governments led by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) may view this constitutional position as an impediment to their long-term goal of independence. However, they have been careful not to challenge it openly, recognizing that the existing constitutional framework has served as the bedrock of peace and stability across the strait for more than seven decades.

On the other hand, those in Taiwan who advocate for independence want nothing to do with the mainland. While their ancestry may trace back to the mainland, they feel no emotional attachment to it. For them, Taiwan is a distinct political and cultural entity, and the idea of reunification holds no appeal.

Meanwhile, public opinion in Taiwan remains centered on maintaining the status quo. According to polls, the majority of Taiwanese do not support immediate moves toward either formal independence or unification. Instead, they prefer to preserve the current ambiguous state of de facto independence without declaring it outright, in order to avoid provoking conflict while preserving autonomy.

Resolving the Differences

The U.S. and China clearly have irreconcilable differences. China couldn’t care less about the U.S. political system; the only things it wants to export are goods, not ideology. However, it views the U.S. as a roadblock to its reunification efforts and is deeply anxious that Washington may encourage Taiwan’s independence. Chinese people do not hate Americans, but U.S. behavior regarding the mainland–Taiwan issue is a major source of resentment. Officially, the U.S. maintains strategic ambiguity on the Taiwan issue, but its actions consistently suggest an intent to thwart reunification.

On the other side of the Pacific, the American people have no inherent hostility toward the Chinese people or their culture. But they harbor deep suspicion and discomfort toward the Chinese Communist Party—and growing anxiety over China’s rise as a global power. There is no realistic scenario in which the Chinese people would accept Taiwan’s independence. And there is no realistic scenario in which the American public would feel truly at ease with a powerful, Communist-led country that may soon rival or surpass the U.S. in global influence.

This difference is indeed irreconcilable—but it is not necessarily fundamental. It stems from the presence of communism in the equation. If that ideological factor were removed, a new landscape of possibilities might emerge—one in which the core concerns of both sides could be addressed. In that sense, the conflict becomes solvable. It becomes possible to hit two birds with one stone.

It should be emphasized that communism is not only foreign to Chinese civilization—it is fundamentally antithetical to it. The Chinese people never asked for it; it was imposed on them when the Communist Party took over the mainland in 1949. During the war against Japan, Communist forces expanded significantly while the Kuomintang (KMT) bore the brunt of the fighting. By the time Japan was defeated, the Communist forces were strong enough to overwhelm a greatly weakened Nationalist army.

The key question, then, is how to remove communism from the equation—not through brute force, but through creative statecraft that builds trust and minimizes destabilization.

The PRC’s Dubious Past

The origins of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) can be traced back to a puppet regime called the “Chinese Soviet Republic,” established in 1931 in Jiangxi Province. This proto-state was funded and directed by the Soviet Union’s Comintern. Its explicit objective was to overthrow the Republic of China and establish a government loyal to Soviet interests.

During the Second Sino-Japanese War, the Communists focused less on fighting the Japanese than on expanding their power base. They often avoided major confrontations with Japanese forces and instead capitalized on the chaos to absorb territory and recruit members. By the time World War II ended, they had significantly strengthened their position.

After seizing power in 1949, the new Communist regime proclaimed that it would not recognize the so-called “unequal treaties” imposed on China by Western imperial powers—with the notable exception of those signed with Tsarist Russia. In practice, the PRC voluntarily ceded vast tracts of Chinese territory to the Soviet Union in the name of fraternal socialism.

In 1951, the PRC also acquiesced to India’s de facto annexation of South Tibet. By the mid-1950s, Beijing even offered to formally cede the region to New Delhi. India never accepted the offer, and the failure to resolve the issue has left a lingering territorial dispute between the two countries to this day.

American Political Capital

The Opium War (1839–1842), fought between China and Britain, decisively exposed the Qing dynasty’s weakness in the face of a newly industrialized Western power. As a result, Hong Kong was ceded to Great Britain as a war bounty. The war marked the beginning of what Communist China later termed the “Century of Humiliation.”

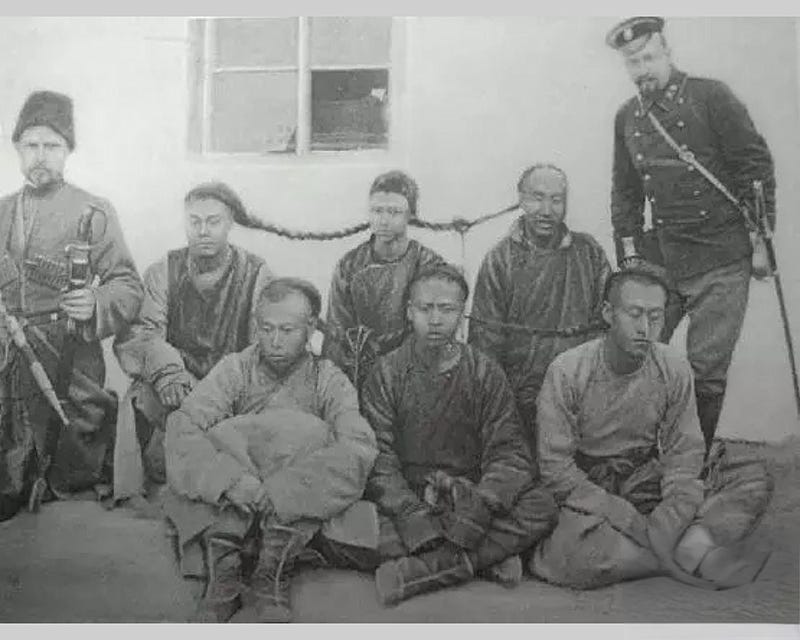

During this period, various Western powers gained extensive privileges in China: Britain and France secured extraterritorial rights and trade concessions in major cities; Germany obtained a lease in Shandong and established a major naval base in Qingdao; and Russia, through the Treaty of Aigun (1858) and the Treaty of Peking (1860), acquired vast territories in the northeast, including access to the Pacific—land that now forms the area around modern-day Vladivostok. Russia also committed massacres in China (for e.g. the Blagoveshchensk Massacre[7]The Russian Massacre of 1900 and the Sixty-Four Villages East of the River Massacre)—yet these acts are rarely acknowledged in broader historical discourse.

In the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), Japan seized Taiwan. The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) brought a full-scale invasion, along with atrocities such as the Nanjing Massacre and the biological warfare experiments conducted by Unit 731 in northeastern China.

So where did the United States stand in all of this?

Although it was part of the Western world, the U.S. played a minor role in the imperialist enterprise. A distinction must be drawn between the United States and what some have called “Old Europe.” The U.S. generally maintained a friendly posture toward China. Its “Open Door Policy” (1899, 1900) explicitly called for respect for China’s territorial and administrative integrity, opposing the division of China into colonial spheres of influence.

On multiple occasions, the U.S. acted to defend Chinese interests and even mediated with other Western powers on China’s behalf. After the Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901), the United States negotiated with other nations to reduce the amount of indemnity demanded from China. Unlike the European powers, the U.S. never threatened territorial annexation, imposed unequal treaties, or extracted trade concessions through gunboat diplomacy.

In fact, the U.S. was the only nation to forgo its share of the Boxer Indemnity. Instead, it used the funds to sponsor Chinese students to study in the United States.

Beyond that, American missionaries and philanthropists built hospitals, founded universities, and operated charitable institutions across China, leaving a positive and long-lasting legacy.[8]American generosity was not confined to China. The United States was equally charitable in the Middle East during that era. As in China, the U.S. showed no territorial ambitions in the region. Instead, its efforts were largely missionary in nature—focused on building hospitals and universities. The American University of Beirut, for example, was founded by Americans with the goal of advancing education in the region. Unfortunately, the United States has since squandered much of the goodwill it accumulated during the colonial era.[9]Peking Union Medical College Hospital – Wikipedia[10]History of the Tsinghua University

Even before World War II formally began, American pilots—the Flying Tigers—were already operating in southwest China. They engaged Japanese aircraft in combat and worked to keep the Burma Road open so that essential supplies could continue flowing into China.

Despite these efforts, Communist China has often labeled the United States an imperialist power, largely for domestic political purposes. Curiously, few Western pundits push back against this characterization—perhaps out of ignorance or indifference—thereby allowing Communist China to get away with what amounts to historical defamation.

These are reserves of political capital the United States has never truly tapped into. Today, after more than seventy years of media monopoly by the Chinese Communist Party and the shaping of an official historical narrative, most Chinese citizens—especially younger generations—are unaware of the goodwill once shown by the U.S. Instead, they lump America in with other colonial-era powers as just another agent of China’s historical subjugation.

U.S. Initiative

The President of the United States should speak directly to the Chinese people and leverage their collective sentiment to encourage a political transformation within China. The following is a proposed letter:

Letter from the President of the United States

Addressed to the Chinese People

Dear Chinese People,

I would like to take this opportunity to speak directly to you, for the benefit of both our nations.

Given the different paths our countries have taken through history, it is natural that our national concerns diverge. For you, national unification remains a deeply held aspiration. For us, it is the challenge of a rising power governed by a Communist Party—an ideology we view with grave concern based on our own historical experiences.

We understand your desire for national unification, and we have, in the past, not stood in opposition. In fact, we clearly articulated our position on this matter in the Shanghai Communiqué, issued during President Nixon’s historic visit to your country in 1972: There is one China, and Taiwan is a part of China.

However, as you can understand, unification on the current terms—specifically, the incorporation of the polity on Taiwan into the People’s Republic of China—would entail the dissolution of the Republic of China. This is something we cannot support, for it would constitute an abandonment of historical truth and a betrayal of our shared past.

You are surely aware that during World War II, the Republic of China and the United States fought side by side against Imperial Japan. Of the more than 430,000 Japanese soldiers who died in the China theater, over 429,000 were killed by Nationalist forces. The Republic of China’s military also worked with our Flying Tigers, resisting the Japanese Air Force and keeping the Burma Road open, which allowed vital supplies to reach Chinese soil. It was the Nationalist army that bore the brunt of the defense of China—not the Communist forces[11]According to statistics from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare in 1963 regarding the number of Japanese soldiers killed on the Chinese battlefield, between July 7, 1937, and August 14, 1945, a total of 431,100 Japanese soldiers died—26,500 in Northeast China and 404,600 in other parts of China. Of these, only 851 were reported to have died at the hands of the Chinese Communist forces. At the Yasukuni Shrine in Japan, a plaque commemorates each fallen Japanese soldier with their name, place of origin, and date of birth and death. Among them, the records detail the 851 soldiers who died in battle against the Chinese Communist Army.. The friendship between our two peoples transcends politics even when the politics are at odds. When the Soviet Union attempted to use nuclear blackmail against the People’s Republic of China in 1969, it was President Nixon who raised the U.S. nuclear alert level to warn the Soviets to back off.

Therefore, in accordance with both the letter and spirit of the Shanghai Communiqué, we now announce our decision to return to the diplomatic status quo as of December 31, 1978 (one day before the U.S. formally recognized the PRC). Specifically, we are re-recognizing the Republic of China as the sole legal government of China, with sovereignty over the territory defined in its constitution.

While we had hoped to preserve our relationship with the governing authority on the mainland, we respect the Chinese people’s commitment to the ‘One China’ principle. As such, we are compelled to make the difficult decision to sever diplomatic ties with the mainland government.

To further honor historical truth and Chinese territorial integrity, we also support the return of South Tibet—separated from China in 1951—to Chinese sovereignty[12]How South Tibet became Arunachal Pradesh. We also urge the leadership on the mainland to consider a transition away from the Communist Party toward a political framework that meaningfully addresses our enduring concerns about communism. In the course of this potential realignment, we remain committed to fostering a constructive and mutually respectful unofficial relationship with the government on the mainland.

A well-placed strike to Talos

China wants reunification—well, the U.S. can facilitate that. Trump must read this letter at the United Nations to underscore his commitment and to maximize its exposure. This letter essentially flips the script and turns the issue of unification into a real-world example of the idiom: “Be careful what you wish for.” It is the equivalent of a well-placed strike to Talos. It would be so ground-shaking that, within 24 hours of his address, the vast majority of Chinese citizens would have heard about it, creating a buzz among the people and throwing the Communist leadership into a state of shock, at a loss for how to properly react.

The Chinese Communist Party would immediately find itself on the defensive. Its mastery of stoking nationalism, honed over decades, would backfire in this instance. The letter sidesteps confrontation and instead positions the United States as finally “getting it”—aligning with Chinese nationalism, not against it. Here’s a shocking revelation about the Communist leadership—or perhaps any leadership: they don’t truly care about communism. What they care about is staying in power—or, at the very least, avoiding the fate of Romania’s Nicolae Ceaușescu in 1989. The grand bargain not only doesn’t harm China’s national interest—it actually promotes it. This is an offer that common Chinese citizens would find hard to refuse.

The letter also subtly reignites the topic of who truly fought Japan in WWII. Chinese citizens would not take kindly to the implication that the Communist Party played almost no role—or even a spoiler role—in that war. It would also signal to the Chinese people that the United States looked out for China’s interests when the Soviet Union attempted to blackmail China with nuclear threats. The aim is to foster a sense of affinity toward America among the Chinese population.

The letter also highlights that a piece of territory, South Tibet, was carved out from China under the Communist Party’s watch, and that the Communist Party has kept the public in the dark about it for decades. That the U.S. supports its return to China.

A Grand Bargain

If handled with finesse, President Xi could achieve the ultimate prize: the unification of China. He could seize the moment, disband the Communist Party, and establish a new political party free from the baggage of foreign ideological origins. Politicians in democracies form new parties all the time—why not Xi?

After all, the Chinese economy is no longer Communist in practice. It is arguably more capitalist than that of the U.S. Retaining the term “Communist” in the party’s name is a relic of history. Rebranding it to reflect reality is only appropriate.

Alternatively, Xi could resist—insisting that the Communist Party will not yield—and risk facing the wrath of the people.

The beauty of this initiative is that it is politically palatable to both sides. Xi can claim the historic achievement of unifying China, while Trump can rightfully boast of having defeated communism without firing a single shot. It would also revive the original geopolitical spirit of the Shanghai Communiqué—which has long outlived its relevance—ushering in a new era of U.S.–China cooperation, once again aimed at countering Russia.

References

[1] There is now a popular belief among younger generations that what happened in June 1989 was a CIA-engineered color revolution. It was not—at least not in the beginning. The way it unfolded was entirely indigenous and organic.

U.S. foreign policy toward a country can swing wildly like a pendulum, depending on the political expediency of the moment. Exhibit A: Iraq. When Saddam Hussein invaded Iran, the U.S. supported Iraq by providing satellite imagery of Iranian troop positions. A few years later, when the same Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, he suddenly became U.S. public enemy number one.

In 1989, the Cold War was still in full force, and the U.S. and China were in a period of détente. The Soviet Union would dissolve two years later, but no one could have predicted that at the time. In fact, the U.S. Seventh Fleet was patrolling the East and South China Seas with China’s blessing, as a counter to Soviet aggression. The CIA operated a radar station in Xinjiang to monitor Soviet activity in western China, and a U.S. defense contractor was helping China modernize the radar system on its J-8 fighter jet.

At that time, the U.S. was more worried about China being too weak than too strong. It had no reason to destabilize China.

[2] In terms of freedom, the freest period in Hong Kong was the first decade and a half following the British handover to China. During that time, despite portrayals to the contrary in much of the Western media, Hong Kong enjoyed greater civil liberties than it had under British rule. Specifically, there were actions people could take post-handover that would not have been permitted under colonial governance. For example, after the handover, banners calling for the downfall of the Chinese Communist Party could be seen hanging in some of the busiest districts in downtown Hong Kong—something that certainly would not have been allowed during British rule.

Understandably, the British were sensitive to anti-colonial sentiment in Hong Kong, but they also suppressed anti-Chinese Communist Party activism. The colonial administration preferred Hong Kong society to remain apolitical. Moreover, British-ruled Hong Kong was not a democracy. Conversely, there was nothing people were allowed to do under British rule that they could not also do in the early years after the handover.

Following the handover, Hong Kong adopted a representative form of government, with elections contested by political parties that reflected a range of viewpoints—some leaning pro-Beijing, others leaning anti-Beijing. However, after the 2019 unrest, Hong Kong enacted a national security law that significantly restricted civil liberties and effectively marginalized or outlawed political parties and activists viewed by Beijing as troublesome.

[3] China’s economy is no longer communist; it is arguably more capitalistic than that of the United States. However, in terms of geopolitical narrative, it remains, for all practical purposes, a Communist country.

[4] China and its Ethnic Policies

[5] Is the genocide figure of 1.2 million reliable?

[7] The Russian Massacre of 1900

[8] American generosity was not confined to China. The United States was equally charitable in the Middle East during that era. As in China, the U.S. showed no territorial ambitions in the region. Instead, its efforts were largely missionary in nature—focused on building hospitals and universities. The American University of Beirut, for example, was founded by Americans with the goal of advancing education in the region. Unfortunately, the United States has since squandered much of the goodwill it accumulated during the colonial era.

[9] Peking Union Medical College Hospital – Wikipedia

[10] History of the Tsinghua University

[11] According to statistics from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare in 1963 regarding the number of Japanese soldiers killed on the Chinese battlefield, between July 7, 1937, and August 14, 1945, a total of 431,100 Japanese soldiers died—26,500 in Northeast China and 404,600 in other parts of China. Of these, only 851 were reported to have died at the hands of the Chinese Communist forces. At the Yasukuni Shrine in Japan, a plaque commemorates each fallen Japanese soldier with their name, place of origin, and date of birth and death. Among them, the records detail the 851 soldiers who died in battle against the Chinese Communist Army.

RSS

RSS