A White, Suburban City

“While the detached suburban home was seen as quintessentially Australian, the urban flat or apartment was European—French, German or more likely middle European, which like cosmopolitan was a derogatory term in this period and a euphemism for Jewish.”[1]S. O’Hanlon 2008, ‘Dwelling together, apart: The Jewish presence in Melbourne’s first apartment boom’, Australian Jewish Historical Society Journal 19(2), p.237-247, p.239.

During the post-war era, a radical change swept across the urban landscape of the city of Melbourne, marking a turning point in its built form. A city comprised overwhelmingly of detached suburban houses began to see the large-scale emergence of a new, very foreign living typology seeking to challenge this hegemony—the flat.

Flats, also known as units, were the clustered forms of accommodation located within a single building that began cropping up en masse on allotments in the beachside neighborhoods of St. Kilda, Middle Park and Elwood. This growth started slowly at first, but caught speed in the mid-1960s, and flats were soon sprouting in suburbia at an alarming rate, an alien incursion entirely distinct from the existing dwelling and streetscape patterns. Often built in the style that became colloquially known as “six-packs,” referring to the number of flats inside, these modern multi-story buildings generally contained between 6–18 dwellings across the floorplan, thereby multiplying rents and occupants of land tenfold. Where flats appeared, private gardens and greenery withered, and what little area the building didn’t occupy was paved over for car parking and driveways to service the multiple occupants where there was previously only one. From the years 1954 until 1977, the number of occupied dwellings located within a flat complex quintupled from around 26,000 (accommodating less than 3% of Melbourne’s total population) to over 125,000.[2]S. O’Hanlon 2014, ‘A Little Bit of Europe in Australia: Jews, Immigrants, Flats and Urban and Cultural Change in Melbourne, c.1935—1975’, History Australia, 11(3), p.116-133, p.120.

Vast swathes of streets and neighborhoods came to be dominated by these overbearing buildings, and construction of detached houses on the other hand practically disappeared during the apex of the flat boom in some suburbs. In the two years from 1962 to 1964 in the suburb of Prahran, 33 houses were built to 1,337 buildings containing flats, and in the same period in St Kilda, no houses were constructed compared to more than 1600 flats.[3]R. Rivett, ‘Flats are Taking Over’, The Canberra Times, 14 September 1965, p.2 These beachside suburbs were the worst hit and the trend swept further eastwards into places like Caulfield and Hawthorn. In others suburbs, flats were kept at bay along major arterial roads, their intrusion into the depths of suburbia vehemently resisted by local councils and residents. The success of the flat typology in Melbourne and elsewhere in Australia soon encouraged developers to build higher, and Australians watched in dismay at the encroachment into their neighborhoods and their city of a high-density living style once so foreign to them, craning their heads up towards new high-rise apartment towers.

Early Flats

Prior to this boom in flats and the subsequent entry of apartments[4]A note on usage: In modern Australian parlance, a flat or unit generally refers to a dwelling in a smaller building, mostly the older two-story walk-up types. Once the building becomes large and tall enough for an elevator, the reference to the dwelling and the building usually changes to an apartment and apartment tower, the word apartment being a later neologism in Australia. and high-rise living onto the scene, Melbourne’s urban form overwhelmingly reflected the mores of its culturally and racially homogeneous white population. With plenty of land to spare, housing throughout the city was typified by detached dwellings on quarter-acre suburban blocks or double-story Victorian terraced houses within the oldest inner-city suburbs. Containing healthy backyards with space for gardening and backyard sports, these single-family dwellings were representative of the predominant desire for an overall green, low-density, private, and individualistic living style. By contrast, flats pre-World War II were a rarity all but avoided by the middle and working-class majority in nuclear family arrangements, and were confined far from the growth of suburbia.

The earliest of multi-family buildings in Australia would seem to modern observers as more akin to a hotel than a home, where instead of self-contained kitchens, they possessed a central kitchen and a staff of servants to attend to the residents in common dining rooms. These early buildings, many renovated from defunct mansions due to shortages of domestic staff (the servant problem as it was known), gave way to the first true self-contained flats during the inter-war period. Limited to the affluent suburbs, flats functioned primarily as investment vehicles and haunts for the wealthy that were never intended to displace the detached house as the main residence. They were often a convenient secondary or tertiary home for country dwellers visiting the city, rented out to the elderly and the widowed, or supplied to bachelor offspring. These flats were heavily restricted by planning codes at the time and came in the era before liberalising inventions such as strata title s and off-the-plan sales contracts. Lacking support from traditional financial institutions, which largely avoided funding them, flats were also expensive to develop. They were primarily rented out, which limited investment returns to rental returns, and where flats were sold, this had to be financed and arranged under complex Company Title laws, whereby ownership of a dwelling in a building was allocated by shareholding in a company, rather than by being subdivided into individual ownership titles. These shares could not be mortgaged and any sale or transfer of ownership had to be approved by the board of the company. Melbourne’s predominate flat architects and developers prior to World War II, the likes of Howard Lawson, and Walter Butler, operated for this small and uniformly affluent clientele in the streets of South Yarra and along St Kilda Boulevard, and the tallest residential building at the time, the 8-story Alcaston House on Collins Street, was built only a stone’s throw away from Victoria’s seat of power, Parliament House, expectedly housing the wealthy and the elite.

The Australian Dream

Subversive to established lifestyle norms and the Australian Dream, and fuelling the rise of cosmopolitanism and multiculturalism, this mass proliferation of flats and apartments in the post-war era aroused widespread and consistent angst and opposition from Australians, who were concerned about the social and cultural effect of the uptake of this new living typology on their cities. To understand the source of popular opposition to flats, as well as how radical these changes truly were, one must delve into the Australian psyche at the turn of the twentieth century, a time when a detached house was intimately linked with the emergent Australian Dream, whereas flats and apartments were linked with squalor and moral impropriety, as well as a subversive and foreign living style considered unnecessary and unsuited to the Australian way of life.

The Australian Dream, a derivation of the similar but not identical American term, grew out of the egalitarian ideals of the late 1800s and held broadly to a vision of a universally propertied nation, with the old class divides between the property haves and have-nots abolished in the New Britannia, signifying greater opportunities for social mobility and freedom. As well as its egalitarian thrust, it was believed that ownership of one’s own block of land and home, the essence of the Australian Dream, would lead to prosperity and political stability, as well as produce a healthy population living in clean air away from industrial pollution, political radicalism, and other immoral influences. At this point, the ideas of Ebeneezer Howard and the Garden City/City Beautiful movements were reaching their crescendo, and most tracts of land were subdivided in mind of a detached dwelling with plenty of space for a garden. As early as the 1930s, Australia likely held the crown for the most suburban country of all nations, as well as possessing an extraordinarily high homeownership rate, an achievement almost unmatched by other countries in the West. In the face of this distinctly Australian achievement, living in a flat represented almost a complete negation of the Australian Dream as a cultural aspiration and was in fact seen as a danger to the Australian way of life.

Butler-Bowden & Pickett argue that the prospect of mass flat living oscillated between two unwelcome extremes in the Australian mind, evoking images of Continental European hedonism and radicalism, as well as of tenement blocks and slum living.[5]See Chapter 1 ‘Slums of the Future?: A century of controversy’ in C. Butler-Bowden & C. Pickett, 2007, Homes in the Sky: Apartment Living in Australia, Miegunyah Press, NSW, Australia. Seen as crowded, unhealthy, and fostering undesirable social outcomes, the latter was in many ways a leftover of imagery from the worst days of the industrial revolution, where the influx of people into cities was followed by overcrowding, pollution and disease, and other social and political ills abounded. Socialist agitation in Europe drew much of its strength from these crowded urban masses, and the fear of falling birth rates from flat living were two political liabilities that Australia’s liberal elite were always keen to avoid. Despite this apparent contradiction in rhetoric between flats as the domain for the bohemian upper-class as well as for impoverished criminals, what was constant to all these elements was the danger to family life and the physical health of the nation, as well as an overall lack of patriotism. Whether it was the malnourished child growing up in the crime-ridden squalor of the slum flat, the bachelor-radical eschewing the bourgeois ideas of family life whilst living in the Bauhaus living-unit, or the un-married, childless heiress living in luxury in the The Astor, the threat to Australia’s future demographic vitality remained the same. Historians the likes of Charles Bean exemplified the patriotic opposition to flat living in Australia as a national danger, fearing that if flats replaced the classic Australian cottage, the ANZAC national spirit would disappear.[6]Ibid., p.2.

(See Chapter 1 ‘Slums of the Future?: A century of controversy’ in C. Butler-Bowden & C. Pickett, 2007, Homes in the Sky: Apartment Living in Australia, Miegunyah Press, NSW, Australia.)

Consequently, the first emergence of flats after World War I was a worrying portent for politicians, residents, and moral arbiters of the time, keen to see the trend limited if not outright restricted, and a variety of laws were passed throughout the states of Australia to ban them or otherwise contain them in suburbs for the wealthy, who were considered less susceptible to the detrimental impacts of flat living. The aggravated tone of the debate on flats during the interwar period is highlighted by Anne Longmire in The Show Must Go On, her history of the City of St Kilda (where the flat boom in Melbourne would soon become most apparent), quoting the vice-president of the Elwood Progress Association—an organization formed to combat flats in their neighborhood:

Flats were destructive of the best citizenship, and home builders should have the protection of the council against the intrusion of them into streets of family residences.” Supporting his case, the St. Kilda Press of 25 May 1935 argued that the city was becoming “pock-pitted” by undesirable buildings, and the one-family home would cease to exist unless zoning was introduced so that St. Kilda would not be “blighted” any further. A year later Cr. Robinson said at the annual meeting of the Progress Association that although the increase of flats had increased rate revenue, “they were attracting a type of people that were not desirable in the best interests of St. Kilda.[7]A. Longmire 1989, St Kilda – The Show Goes On: The History of St Kilda Vol. III, 1930 to July 1983, Hudson Publishing, Australia, p.65.

Attitudes such as these continued to hold among the native post-war population. However, by the late 1950s the defences began to buckle as rates of migration from Europe gathered speed. Demand also came from the new generation of young adults, the nascent baby boomers, who saw flats as a “launching pad for freedom.”[8]R. Thompson 1986, Sydney’s flats: a social and political history, Macquarie University, p.171, retrieved from: http://hdl.handle.net/1959.14/90117 Renting a flat or “flatting” became synonymous with unmarried youth seeking to lead transient sex lives away from the prying eyes of parents and close neighbours,[9]S. O’Hanlon 2012, ‘The reign of the six-pack: Flats and flat-life in Australia in the 1960s.’, In S. Robinson, & J. Ustinoff (Eds.), The 1960s in Australia: People, Power and Politics, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, p.42. and flats were a cheap housing choice for young women attempting to remove themselves from the social expectations of family life. A popular example of the association of flats with sexual liberation was the subversive television soap opera Number 96, which first broadcast many of the ideas of the sexual revolution to mainstream Australian audiences. Set in the eponymous fictional flat building in the Sydney suburb of Paddington, Number 96 ran from 1972 to 1977 and featured the first homosexual and transgender characters on Australian television. Politically, flats also found currency with the forces of the New Left, whose writings rejected Australian suburban housing as a cultural malaise and who recognized the liberal and assimilationist function of the suburb as a structural and ideological barrier to their desired political changes.

The assault on Australia’s social and housing norms and traditional urban structure that began in earnest after World War II was no mean feat, coming up against deep and entrenched political and cultural opposition to these changes. The force of argument from the New Left, a handful of modernist architects, and the few extant flat developers would never be enough to convince a majority of Australians to support or even take up high-density living themselves. Instead, the task of reshaping the urban form of Australia’s cities and driving the rise of flats and high-rise living, taking advantage of the legal changes to property titles and the migrant influx, was ultimately carried out by an unyielding and determined ethnic group who were at the vanguard of these changes in almost every state in Australia. Fought primarily in the two largest cities, Sydney and Melbourne, this battle was not simply over Australia’s urban form, but over what Australia’s very future identity was to be, a fight that became a defining feature of Australia’s changing culture and demographic makeup from the 1960s onwards.

Re-shaping Melbourne

Upon investigating further, one discovers that this small, statistically insignificant group of people, primarily recently arrived migrants from Europe, made up the most prominent involvement in the post-war proliferation of flats and high-density living into what was once a solidly detached-suburban landscape. As developers, financiers, and architects, but also as residents going against the grain of the Australian Dream and the prevailing suburban living norm, it is Jews that emerge as playing the leading role in breaking through the existing stigma and cultural opposition to bring the flat and high-rise typology en masse to the city of Melbourne.

The first sign of a major break in urban form would come in 1950 with the construction of the 9-story Stanhill flats along Queens Road. Taking the title of the tallest residential building from Alcaston House, Stanhill was something altogether new for the city and challenged not only Melbourne’s height limits but its conservative architectural style. When compared to earlier flats, Stanhill, notes Sawyer:

has no suburban counterparts. Its modernity, height, high site coverage and integration of shops within the block (as opposed to flats over shops) set it apart from any other suburban [flat] block. … [It] anticipates the changing nature of inner-city suburban development, and shares design philosophies with that of luxury flat towers now being erected in St. Kilda Road, some thirty years after Stanhill’s completion.[10]T. Sawyer 1982, ‘Residential flats in Melbourne: the development of a building type to 1950, Honours Thesis, Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning, The University of Melbourne. p.46.

Funded and developed by Jewish brothers Stanley and Hilel Korman from Poland and designed by German architect Frederik Romberg, Stanhill’s glassy, steel-frame design exemplified a major broach of the modernist revolution in Melbourne. Romberg learnt from the Bauhaus master himself, briefly studying directly under Gropius at the ETH in Zurich; he was appalled by the architectural styles he saw upon arrival in Australia as a refugee from Europe.[11]O’Hanlon and others list Friedrich Romberg among the names of Jewish architects. Whilst also a migrant from Europe, Romberg appears not to be Jewish, rather descended from a Prussian family. The oversight potentially due to his presence in a Jewish milieu with a German surname and refugee past. Romberg fled Germany due to his left-wing views and a desire to avoid conscription into the German Wehrmacht. He was committed to the social radicalism of modernist architecture, a goal ultimately facilitated by the Korman brothers, but Stanhill would end up being his largest and most famous work. A number of smaller flat buildings designed by Romberg are dotted throughout Melbourne and a 13-story bachelor flat complex in the city centre was unrealised.

If Stanhill was the early warning sign, then the rest of the army was soon to arrive. When the post-war influx of Ostjuden from Central and Eastern Europe began moving into the traditional Anglo-Jewish precinct of St Kilda and spreading into the surrounding neighbourhoods, flat developments soon followed in their wake. As O’Hanlon notes, “it is no accident that the distribution of the flats built in Melbourne in those years correlates strongly to the residential patterns of this growing Jewish community.”[12]O’Hanlon 2014, op. cit., p.120.

Aided by legal reforms to property titles (the Transfer of Land [Stratum Estates] Act 1960) and supported by the more laissez-faire local governments who saw the viability of flats as a quick solution to deal with the large migrant influx, Jewish developers led the flat development trend throughout the boom years, most prominently in the worst hit municipality—the City of St Kilda. A sample of records reveals that all five applications to build flats lodged in the month of September of 1964 in the City of St Kilda were by Jewish developers; in September of 1966 five of seven applications and in September 1968, all but one of eleven new applications for new flats that month were by Jewish developers,[13]O’Hanlon 2014, op. cit., p.126. O’Hanlon sources this from the Building and Construction and Cazaly’s Contract Reporter, July-September 1964, 1966 and 1968, noting the preponderance of Jewish names. with these figures likely replicated in other nearby councils.

Rather than operating through dedicated property development companies as is the norm today, these flats were primarily built through a collaborative approach between a mixture of builders, accountants, lawyers, architects, and real-estate agents who formed project teams (often creating a corporation solely for the building), organized investor syndicates for funds and pooled resources within the Jewish community over procuring loans from banks, which at the time were hesitant to fund flats. This hodgepodge of funding is reflected in the cheap and unintuitive designs of many of these flats, being little more than rectangular blocks with a skin of bricks. They were in stark contrast to the intricately designed Victorian terraces or Federation-era houses that sat on adjacent lots, there being neither financial means nor desire for architectural effort to assimilate the building into the local character. Dedicated Jewish developer/builders such as Martin Sachs, Adam Martin Adams of Martin Adams Developments, Jack Szwarcbord, Schlomo Itzan and Issac Hatz of Henley Constructions, and Leon Chandler left their mark on the city with countless flat developments to their name. In addition, Jewish real-estate firms Talbot & Co. and Birner Morley supplemented real-estate dealings with their own development ventures, and Jewish law firm Arnold Bloch Leibler (ABL, the law firm of Jewish activist Mark Leibler) found much of its early success in brokering for these property developments. To this day ABL continues to act as a legal advisor for Asian property developers and their apartment towers. Many flats of the era are attributable only to amateur consortiums of Jews, often family-based, who developed flats as investment projects parallel to other businesses and did not specialise in the property industry. These were primarily of the walk-up style so evident in St. Kilda, but a larger example is found in “Orrong Towers,” completed in the early stages of the boom in 1961 at 723 Orrong Road, Toorak. Designed by Herbert Tischer, the 8-story tower was built by the Tischer family-owned business Stuard Industries, which specialised in importing pianos and other musical instruments from Europe.

The Beller Boom

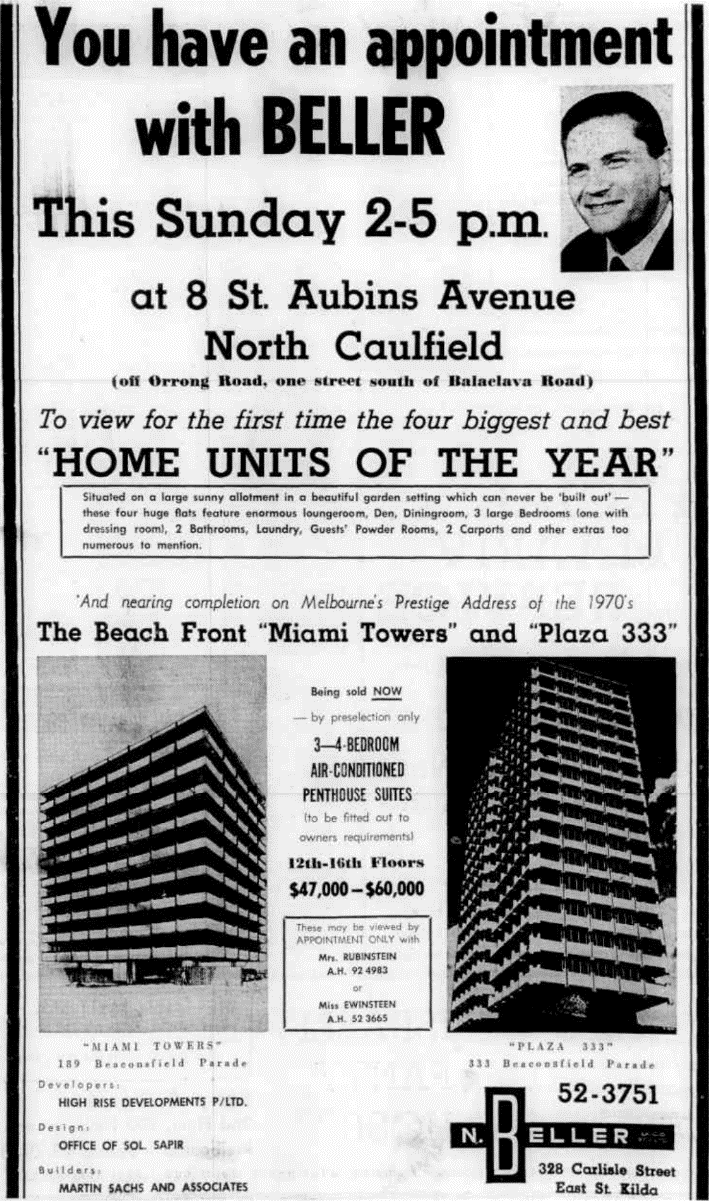

“I see nothing wrong with a high-rise block in a shady suburb street, provided it is designed in good taste.”—Nathan Beller[14]Nathan Beller quoted in The Age; ‘New Style of Life in Towers’, The Age, 19 June 1970, p.21.

As the 1960s drew to a close, the trend did not end with 2-3-story walk-up flats. Further strata title reform came with the Stata Titles Act 1967—based upon the NSW strata law and intended to fix the deficiencies of the earlier 1960 law—which allowed the creation of a Body Corporate to control and manage common property within the building, removing responsibility for the more cumbersome upkeep of a high-rise building from individual owners. This reform opened the way for the intensification of high-rise apartment development, a market soon dominated by an enterprising Jewish developer by the name of Nathan Beller, president of the Victorian Jewish Board of Deputies from 1966–1969. The portfolio of Nathan Beller demonstrates that, emboldened by financial success and strata reform, walk-up flats gave way to taller buildings that began to tower over Melbourne’s low-density landscape. Beller, a real-estate agent by trade turned property developer, fled Austria in 1938 and was responsible for countless flats throughout the inner south and east suburbs, but he arose immediately after the strata reform of 1967 as Melbourne’s main high-rise living exponent, in a partnership with builder Martin Sachs and the architect Sol Sapir.

With Beller’s development company High Rise Developments Pty Ltd (alongside his real-estate agency to sell the flats), multiple examples of their work along the waterfront streets of St Kilda and Elwood are still the tallest structures in the area, towering over the surrounding houses. The Jewish trio collaborated on around a dozen large apartment blocks throughout the inner south-east in the short period between 1967 and 1973, and Sapir claims to have worked on the design of over 100 blocks of flats himself by the year 1971, with many more following afterwards.[15]Built Heritage Pty Ltd, Dictionary of Unsung Architects SOL SAPIR, Retrieved from https://builtheritage.com.au/dua_sapir.html Beller’s advertisements for high-rise flats in local newspapers promoted the cosmopolitan and progressive image of high-rise living, while denigrating those that settled into a “suburban brick-veneer rut,” the detached dwelling belittled as a “rambling workhouse that gobbled up leisure time.”[16]Advertisement, The Age, 3 October 1970, p.5

Data assembled by this writer of the approximately 60 apartment buildings over 8 stories built in Melbourne between the years 1950 and 1985, indicates that more than 70 percent of these developments involved some combination of a Jewish architect or a Jewish builder/development consortium. Of this, Beller’s team was Melbourne’s undisputed leader of the high-rise trend, building more apartments towers than any other developer until the mid-1970s economic downturn hit.

Émigré Architects

In the years before the flat boom, the scanty examples of flats in Melbourne rarely exceeded 2–3 stories in height and architects would make a conscious effort to blend the built form into the low-rise streetscape, often massed to appear from the street as an English mansion or a single-family dwelling—an architectural genuflection to the desired detached-suburban form. The typical English concern for privacy was incorporated, rejecting common entrances in favour of multiple access points that led to only portions of the building or to a single dwelling. Such outcomes soon became forgotten, because even in the architectural composition of flats built during the post-war boom, the preponderance of new forms of urban thinking hostile to mainstream sentiment is evident, mostly imported from abroad by “émigré architects,” a popular euphemism for Jewish architects found in literature on the topic. The few Australian architecture firms who designed flats and high-rise buildings in Melbourne during this period (notably Moore & Hammond, who designed two larger towers along Toorak Road for suspected Jewish clients) are outnumbered by the likes of Mordechai Benshemesh, Sol Sapir (Sapirshtein), Herbet Tischer (Tichauer), Michael Feldhagen, Bernard Slawik, Theodore Berman, Anthony Hayden (Hershman), Ernest Fooks (Fuchs), Anatol Kagan and Kurt Popper, who feature among the roster of Jewish architects whose portfolios overflow with flats and towers in Melbourne. Often applying modernist styles learned in universities in Europe[17]See entries at: Built Heritage Pty Ltd, Dictionary of Unsung Architects, Retrieved from https://www.builtheritage.com.au/dictionary.html. The relative dearth of flats mentioned in the portfolios of non-Jewish architects is notable, their portfolios instead predominantly highlighting detached dwellings and commercial buildings, and flats are otherwise absent from the portfolios of Melbourne’s most prominent firms of the day such as Bates Smart and McCutcheon or Oakley & Parkes., this group of Jews has only recently seen recognition in architectural history journals, despite their overrepresentation in the trend. Earlier publications preferred to highlight the well-formed design of Robin Boyd’s sole tower output, “Domain Park” (developed by Lend Lease), rather than a dozen cheap and less palatable designs by Sol Sapir. Born in Melbourne to Jewish parents who migrated from Poland, Sapir was the most prolific flat and high-rise architect in Melbourne of this group; at least 15 high-rise blocks built during the early high-rise era, most of them developed by Beller, are attributable to him.

Of the other productive architects of this group, we find in Kurt Popper the quintessential story of a Jewish émigré architect subverting the Australian Dream. Arriving from Vienna, Popper was responsible for over 80 blocks throughout Melbourne,[18]O’Hanlon 2014, op. cit., p.122. and later became a lecturer on high-rise apartments in the School of Architecture at the University of Melbourne based off of his expertise in flat and high-rise design. These included four of the earliest apartment buildings in the central business district—city-living pioneers when Melbourne’s centre was practically deserted after business hours and was comprised almost entirely of office and retail buildings well into the 1990s. These were: Crossley House at 51 Little Bourke Street (completed in 1966 by Jewish builders Notkin Constructions), Park Tower at 199–207 Spring Street (completed in 1969, also by Notkin Constructions), 13–15 Collins Street (completed in 1970 by a Jewish development consortium), and Lonsdale Heights at 131 Lonsdale Street respectively. The at-the-time towering Collins and Spring Street buildings (22 and 20 stories each) struggled to attract local purchasers still adverse to apartment living. The Collins Street tower was partially converted into office and retail spaces and only 25 percent of units were sold in the Spring Street tower two years after completion.[19]D. Atyeo, ‘Few takers for O-Y-O Flats in the City’, The Age, 17 February 1971, p.3. The 20-story Lonsdale Heights tower was developed by Hotelier Les Erdi, a Jewish-Hungarian refugee, and included 135 flats alongside the Chateau Commodore Hotel. The hotel dining room became a regular venue for Zionist and other Jewish organisation meetings and Popper was a popular choice for the design of Jewish community buildings throughout Melbourne, with several synagogues, schools, and kindergartens on his resume.

Mordechai Benshemesh, who arrived in Australia in 1939 from what was then still Palestine, also dabbled in property development with his own company Lakeview Investments, alongside his flat design output. He is notable for designing the 13-story Edgewater Towers on the waterfront in Elwood for developer Bruce Small. Edgewater was Melbourne’s first residential building to exceed the 10-story mark and was arguably the first true “residential skyscraper,” taking the title of the tallest residential building from Stanhill. In 1961, his reputation as a leader in the high-rise trend became evident when he was invited to participate in a forum in Sydney alongside fellow Jewish architects, Harry Seidler and Neville Gruzman to speak on the topic of apartment buildings.[20]Built Heritage Pty Ltd, Dictionary of Unsung Architects MORDECHAI BENSHEMESH, https://www.builtheritage.com.au/dua_benshemesh.html

Finally, Ernest Leslie Fooks’ influence is apparent not simply in his architectural output but also as an early town planner, allegedly the first lecturer on the subject at Melbourne’s Royal Institute of Technology. As a student in Vienna, Fooks was employed at the architectural firm Theiss & Jaksch and worked on the “Hochhaus Herrengasse” (built in 1930), at the time Vienna’s tallest residential building and the first non-religious building to protrude above the rooftops of the historic Viennese Old City. Proud of his involvement in the project, Fooks took his photos of the building with him when he fled Austria in 1938.[21]RMIT Design Archives 2019, Special Edition – Vienna Abroad, Volume 9, p.41. In 1946, whilst working as a planner at the Victorian Housing Commission, Fooks published X-Ray the City!: The Density Diagram, a novel work in Australia with an introduction by H.C. Coombs, the then federal director of Australia’s post-war reconstruction department. In it, Fooks advocated for density as a planning solution to Australia’s growing cities and the inequality of social and cultural infrastructure, and critiqued the popular sentiments that equated density with social delinquency—arguments that may have seeded some of the initiative within the state Housing Commission to build the now-hated housing commission towers. Fooks also put his ideas into practice in his private architectural output, being responsible for the design of another 40 blocks of flats in the boom suburbs during the era,[22]O’Hanlon 2014, op. cit., p.122. as well as a number of Jewish community buildings and schools, notably Mount Scopus College.

A New Generation

The financial crisis of the mid-1970s followed the suburban backlash, and, as the boom in construction ultimately dried up, the flow of new flats dwindled to a trickle. The flat boom peaked in the years of 1967–1968 where around 13,600 dwellings were added, crashing to 2,400 by 1979–1980.[23]M. Lewis 1999, Suburban Backlash—The Battle for the World’s Most Liveable City, Bloomings Books, Australia, p.91 That the high-water mark for flat development exactly coincided with the year of the arrival of the cultural and sexual revolution reflects the connection between the two phenomena. While not as fierce as in Sydney, Melbourne-based Green Bans stifled their fair share of developments, local councils tightened up planning laws, and resident actions groups began forming throughout the suburbs in response to Housing Commission towers and the flat and apartment boom. The encroachment of Jewish-built high-rise towers, in particular Nathan Beller’s, into the WASP heartlands of eastern Toorak and Hawthorn enraged locals, leading to the establishment of local anti-high-rise groups. An 8-story proposal by Beller at 480 Glenferrie Road opposite the elite Scotch College saw objectors come out in droves, his 9-story block at 3–5 Rockley Road, South Yarra (designed by Sol Sapir) was the final insult to residents on a street overdeveloped with flats, but a tower proposed in the depths of Toorak at 546 Toorak Road (built in 1971 and also designed by Sol Sapir), named Barridene after the mansion that previously occupied the site, garnered the most attention. Local residents submitted over 800 objections to the proposal and the building was eventually cut down from 19 to 13-stories, the outcry becoming the impetus for a blanket ban on more towers in the area. To this day Barridene still looms over surrounding mansions of Toorak and the Presbyterian Church across the road, the church steeple no longer being the tallest structure in the area – an apt example, in urban and built form terms, of Jewish disregard for Christian cultural mores.

After the flat boom ended, a calm set on the Melbourne housing market, as detached dwellings re-asserted themselves, migration slowed, and the Baby Boomers, now with children to raise, shifted to traditional detached housing. This calm would not last long however, as apartment developments re-appeared in the mid-1990s, following initiatives to revitalise the central business district and bring city-living to the heart of Melbourne. Jewish property developers came to the fore once again, former Melbourne Lord Mayor Irving Rockman’s Northrock Investments leading the way with a 58-story apartment tower proposal at 368 St Kilda Road (later reduced to 40 stories) and a 33-story tower at 265 Exhibition Street. Central Equity followed suit in the newly zoned suburb of Southbank with apartment towers at 28 Southgate Avenue and 83 Queensbridge Street, the first in the precinct; Max Beck’s Becton attempted to outdo Nathan Beller with a 38-story tower at the Espy Hotel at St. Kilda beach and Mirvac made steadily erected early towers in the re-zoned Docklands and Southbank precincts. Central Equity, co-founded and now chaired by Eddie Kutner, has become Melbourne’s most consistent high-rise property developer. Largely taking its inspiration from Meriton in Sydney, it has been churning out low-cost apartment towers in the city on average once every year since the early 2000s. The suburb of Southbank, now the tallest in Australia, is almost synonymous with the Central Equity brand—nearly 30 apartment towers south of the river now bear Central Equity’s name. A Zionist like most of his Jewish property developer kin, Kutner’s credentials have seen him involved in the Australia-Israel Chamber of Commerce, Jewish schooling and Keren Hayesod-UIA.

By the twenty-first century, other European migrant communities were also taking the limelight in roles that the Jewish community had paved the way for in the post-war era. Smaller conglomerations of flats had also sprouted in the neighborhoods of Footscray and Northcote, areas popular with Italian and Greek migrants. Italian families such as the Grollo’s, Schiavello’s and Giuliano’s grew their small construction firms into high-rise tower developers in Melbourne from the 1980s onwards, following in the wake of the Jewish community and also seeing the opportunities in flat and high-rise property development as a means of financial success. The development team of the 90-story Eureka Tower (built in 2006), up until recently the tallest building in the city and star of the rise of apartment towers in central Melbourne, symbolised the new state of affairs in property development. It was constructed by Italians (Daniel Grollo of Grocon), designed by a Greek architect (Nonda Katsalidis) and funded by Jews (Tab Fried and his brother-in-law Benni Aroni).

Although overshadowed in scale by the latest generations of property developers—now from China, Singapore and Malaysia—Jewish developers in Melbourne continue to find financial success in providing apartments for the influx of immigrants and profiting off the displacement of the Australian way of life. After 20 years, Central Equity is still going strong, and Jewish developers Meydan Group, Lustig and Moar, R. Corporation, H&F Property, Vicinity, Dealcorp, Debuilt Property, Pan Urban, and LK Property fill the spaces amongst the Asian megatowers. In an interview with a local property website, David Kobriz, the founder of Dealcorp, neatly encapsulated the hostile feeling to earlier Australian society that is now endemic throughout the industry:

Melbourne today is such a cosmopolitan place and you have to look back to the ’50s and ’60s to see where that’s come from… the third and fourth-generation migrants have made the city what it is today. Dynamic, full of variety and catering for a wide range of people.[24]L. Sweeney, ‘Building our city: Dealcorp’s David Kobritz on the need for higher density living in Melbourne, Domain, 30 September 2019, retrieved from https://www.domain.com.au/news/building-our-city-dea...86251/

Kings of High Rise

Due to geographic constraints and restrictive rent controls, Sydney was never quite as suburban and low-density as Melbourne prior to World War II. Early flats were built for the working poor near industrial points of the harbor and luxury towers were constructed along Macquarie Street in the city centre, the first apartment precinct in Australia. The uptake of flats (and the associated stigma) grew during the inter-war years and blocks up to 10-stories high rose in the wealthy and cosmopolitan inner-east suburbs of Elizabeth Bay and surrounds, with no significant Jewish involvement in these events. This growth was in-part spurred by the rent controls of the Fair Rents Act 1915, the law heavily restricting rental returns on land, thus making flats more profitable ventures for wealthy landlords in these built-up areas than a single detached house. The tallest and most exclusive of Sydney’s early flat buildings was The Astor on Macquarie Street, built in 1923, which still possesses uninterrupted views over the Opera House and the harbor. At 13 stories, it was the tallest residential building in Australia for nearly 40 years until overtaken by Blues Point Tower in 1961. Famous occupants included the Jewish feminist Ruby Rich and heiress Dame Eadith Walker, and many of the flats were sold to wealthy pastoralists from rural New South Wales (NSW), who used them as a pied-à-terre.

Tolerated for the rich and used as a last resort to house the poor, these housing outcomes were never considered acceptable solutions for the growing middle-class Sydney population, neither from local residents, local councils, slum reformers or the New South Wales (NSW) state government of both the Liberal and Labor persuasion, all of whom preferred to promote the home ownership ideals of the Australian Dream while doing their best to mitigate flat uptake.[B1]For a detailed account of the New South Wales’s government efforts against flats pre-1939, see Thompson 1986, op. cit., p.25-67. Anti-flat advocates focused their ire on the growth of flats around Kings Cross, which they argued contributed to the area becoming a morally disreputable centre, full of transient residents and rapacious landlords. The suburbs of Elizabeth Bay and Potts Point accounted for 92 percent of all flats in Sydney by the year 1928[B2]Ibid., p.45.

(For a detailed account of the New South Wales’s government efforts against flats pre-1939, see Thompson 1986, op. cit., p.25-67.), the same year that the state government passed the Local Government (Amendment) Bill 1928, which allowed councils to prohibit residential flats. Popular opposition failed to make an impact in the post-war era when immigration increased the pressure for development, and the property industry secured the passing of the landmark Conveyancing (Strata Titles) Act in 1961. The law ended the era of flat developments being primarily a rental venture for investors and fully legalized owner-occupier arrangements, allowing flats and towers to flourish, as developers no longer needed to front the full capital costs of the building and could expect only rental returns for their efforts. The intent of strata titles, at least for the governing NSW Labor Party, was to correct a decline in affordability and rental stock that occurred during the 1950s, which landlords argued came as a result of the failure to remove rent control laws. The scale of development that followed over the next two decades was beyond even the wildest expectations of those who drafted the Act.

After strata titles were introduced, the number of occupied flats and apartments skyrocketed, from just under 60,000 in 1954, to 252,000 by the end of the boom in 1981.[B3]Ibid., p.285.

(For a detailed account of the New South Wales’s government efforts against flats pre-1939, see Thompson 1986, op. cit., p.25-67.) In Melbourne, fewer than 60 apartment blocks over 8 stories appeared between 1960 and 1980; in Sydney the figure was over 450, concentrated on the eastern waterfront suburbs of Port Jackson.[B4]Ibid., p.180.

(For a detailed account of the New South Wales’s government efforts against flats pre-1939, see Thompson 1986, op. cit., p.25-67.) As in Melbourne, these developments were hostile to the cultural aspirations of Australians and aroused fierce opposition in the form of local anti-development groups and the powerful union-based “Green Bans” movement. Attempts by local governments to stem the tide of towers, responding to the howls of protest from ratepayers, achieved little. The boom ran out of steam with the economic downturn of the mid-1970s, when property prices fell and developers offloaded the last of their new flats, finally allowing breathing space for councils to reassess their planning codes and put in place blanket-bans on new towers.

More than any other ethnic group, Jewish property developers and architects would play a leading role in this change in the post-war period and into the twenty-first century, enormously overrepresented in re-shaping Sydney into a sprawling apartment metropolis with the densest population of any city in Australia. Modern property development powerhouses founded in this era—Meriton, Stockland and Mirvac—all have Jewish roots, as do prominent developers of the past such as Paul Strasser and Frank Theeman. Other Jewish property developers not covered in detail in this essay also consistently crop up in the annals of Sydney property history. Sidney Londish of Comrealty and Regional Land Holdings (also notable as an early exponent of shopping centers) and Frank Lowy and Robert Saunders (originally Jeno Schwarcz), founders of the Westfield shopping center empire, also had interests in apartment development. The strong spatial patterns of flat and apartment development in the eastern suburbs of Sydney during this period once again strongly correlate to the traditional Jewish suburbs of Bondi, Woollahra and Paddington (the equivalents of St Kilda in Melbourne), and the growth of the Jewish community from post-war migration into the areas around Kings Cross and Edgecliff. The same over-representative Jewish presence noted in the high-rise trend in Melbourne is evident in Sydney on an even larger scale. Between strata reform in 1961 and the year 1980, more than 50 percent of high-rise apartment developments above 15 stories involved some combination of a Jewish developer or architect.

As the following review will reveal, these Jewish developers varied in the quality of their output and in their moral scruples, but were all consistent in their character as early movers, innovators, and popularizers of the high-density alternatives to the Australian Dream. Gentile developers are counted among the minor players in the burgeoning flat and high-rise industry after 1961;[B5]Mainline and Home Units of Australia, neither of which survived the 1970s downturn; and HUA was far from a local, founded by itinerant Englishman Syd King. nevertheless to discuss the history of flat and high-rise property development in Sydney without reference to these Jews, would be to ignore the most important as well as enduring protagonists of this post-war revolution in Sydney’s urban form.

Parkes Developments

Starting off the review of the key Jewish players in the post-war era is a migrant from Hungary who fled from communist rule in 1948—Paul (Paulus) Strasser. Born to a wealthy Budapest family, Strasser emerged from small financial beginnings in Australia to build Parkes Developments—and its sprawling network of associated and subsidiary companies—into a flat-building empire throughout suburban Sydney, believed to be the largest landholder in Sydney at the time.[B6]C. Butler-Bowden & C. Pickett 2012, ‘Strasser, Sir Paul (1911—1989)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, retrieved from https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/strasser-sir-paul-15741. Co-founded with fellow Hungarian émigré Robert Ryko in 1956, Parkes’ development style piled building upon building, squeezing as many flats as possible onto the land, overwhelming the low-density landscape of the areas they chose to develop. The most egregious example of this may be found in the Sydney suburb of Eastlakes, where in 1961 Parkes Developments built an army of over fifty 3-story flat buildings on land that was once a disused racecourse now surrounding the Eastlakes Shopping Centre. The NSW housing commission rounded out the development with twin 9-story blocks overlooking the nearby single-story houses—designed by Harry Seidler. Other overbearing Parkes flat developments that aroused aggressive local opposition in Sydney include the waterfront redevelopments of the industrial foreshore around Leichhardt Street and Bortfield Drive in Chiswick, the Grace Campbell Crescent flat complex in Hillsdale. Parkes Developments also made many forays into 10-story plus blocks along the waterfront of eastern Sydney and in Kings Cross.

Strasser’s involvement with the closely associated banking and property company Development Underwriting Ltd (with Charles J. Berg and Robert Strauss) also produced a number of flat and retail developments throughout Australia, and his business empire spanned an estimated 70 companies, with interests as diverse as cattle breeding and oil and mining ventures. By the 1970s, an exact account of the ownership structure of Parkes and its intertwined companies became difficult to ascertain (structured primarily to avoid paying high tax rates on privately owned companies[B7]M, Wilson, ‘How Parkes eased a burden’, Sydney Morning Herald, 19 March 1977, p.49.) and allegations of corrupt dealings with NSW Premier Robert Askin, who knighted Strasser in 1973 for “services to building industry and charity,” dogged Strasser’s career. Parkes Development ultimately collapsed in 1977, tens of millions of dollars in debt and Strasser spent his latter years on the managing committee of Mirvac before his death in 1989. A benefactor of Jewish causes, Strasser led the creation of, and was President of Shalom College from 1972–1976, a college for Jewish students at the University of New South Wales.

Stockland

In 1952, Ervin Graf, an architect who arrived in Australia from Hungary in 1950, borrowed £3000 from Albert Scheinberg. From this loan, Graf built the retail and property behemoth Stockland, originally called Stocks & Holdings. Now for all intents and purposes a gentile-run company, Stockland is Australia’s largest property group, with diverse developments of apartments, offices, and shopping center complexes around Australia. Early principal directors Albert and John Scheinberg departed to form their own flat development company in 1974, taking up the suitably “goyisch” name McDonald Industries, but Graf remained at the head of Stockland until his retirement in 2000, the function attended by Prime Minister John Howard.[B8]C. Cummins, ‘Architect whose faith in property’s potential paid off’, Sydney Morning Herald, 29 July 2002, retrieved from https://www.smh.com.au/national/architect-whose-fait....html. An advocate for high migrant intake and a pioneer in bringing high-rise living to Sydney, Graf was among the first to take full advantage of the changes to strata titles in 1961. Stockland began its venture in high-rise apartments in 1952 with a 20-story block at 8–14 Fullerton Street, Woollahra, adjacent to a Jewish hospital. Stockland’s crowning achievement in high-rise living came in 1964 when Graf completed the Park Regis Tower at 27 Park Street in the center of the city. Dwarfing the surrounding buildings, at 45 stories it was the tallest residential tower in Australia upon completion. Designed by in-house architect Frank Hoffer (also from Hungary), the tower soon became a popular residence for Sydney’s cosmopolitan elite and an icon for the changing cultural mores in Australia during the period.[B9]D. Jellie, ‘A 60’s Icon Turns 40’, Sydney Morning Herald, 22 November 2007, retrieved from https://www.smh.com.au/lifestyle/a-60s-icon-turns-40...p.html Park Regis was unmatched in scale for an apartment tower in Australia for more than 15 years, retaining the title of tallest residential building in Sydney until as late as 1996 when it was eclipsed by Meriton towers. Another benefactor and President of Shalom College (from 1990–1993), the yearly Ervin Graf Memorial Oration was named in his honour and has hosted speeches by Jewish luminaries such as Deborah Lipstadt and Amos Oz; Graf donated to Jewish educational and other causes throughout his life.

Progress and Properties

Founded in 1955 by Tibor Balog and Michael Hershon (Hirschhorn), who both arrived from Hungary after World War II, Progress and Properties was, along with Graf’s Stocks and Holdings, among the earliest property development companies to enter the Sydney high-rise apartment scene. Going public in 1965 after earlier ventures in smaller scale flat development, Progress and Properties was responsible for a cluster of apartment towers in Darling Point, primarily along Thornton Street, ranging from 18–30 stories. The historic Retford Hall mansion was demolished to make way for these towers, and their 30-story Ranelagh Flat at 3 Darling Point Road (built in 1969) became Australia’s second tallest residential building upon completion. In North Sydney, their 23-story block at 50 Whaling Road still projects into the sky with little regard for the single-story houses adjacent, and numerous other flats and sizeable apartment blocks attributable to Progress and Properties are dotted throughout the eastern and inner western suburbs of Sydney. By the mid-1970s Progress and Properties had morphed into Dainford Holdings, which also found success on the Gold Coast, with 15 apartment towers throughout the 1980s. The tallest, the 47-story BreakFree Peninsula at 3 Clifford Street, took the title of the tallest apartment tower in Australia from Stockland’s Park Regis.

Like Strasser and Frank Theeman, Hershon and his partners were among the seedier players of the Sydney property development industry. An investigation by the Sydney Tribune uncovered a number of associations between Progress and Properties and Jewish crime boss Abe Saffron,[B10]Sydney Tribune, “A Tribune Investigation,” 28 March 1984, p.16 and Dainford Holdings collapsed in 1991, shortly after Balog was charged with corruption relating to property dealings with the Waverly Council.[B11]R. Harley, ‘DEVELOPER, PLANNER SENT FOR CORRUPTION TRIAL’, Australian Financial Review, 29 August 1992, retrieved from https://www.afr.com/property/developer-planner-sent-...-k52a5 Further scandal surrounded Hershon, also notable as the head of a lingerie manufacturer, and he was a board member of a number of Zionist organizations and Jewish schools throughout his life.

Meriton

“I looked around and I saw cottages everywhere… I thought it was time they lived in apartments.”- Harry Triguboff[B12]Sydney Morning Herald, ‘Triguboff and the new Great Australian Dream’, 24 November 2010, retrieved from https://www.smh.com.au/business/triguboff-and-the-ne...h.html

Still privately owned by Harry Triguboff, the success of Meriton embodies the revolution that Australian urban form has undergone. The company has grown to become the largest apartment developer in Australia, a builder of copious quantities of low-cost units and towers in New South Wales and Queensland. The company estimates it has provided more than 75,000 apartments in Australia since its inception.[B13]‘About Meriton’, Meriton, retrieved from https://www.meriton.com.au/about-us/ A mainstay of rich lists, at one point the wealthiest person in Australia, in 2020 Triguboff was the third richest person in Australia with an estimated wealth of $15.5 billion, behind only mining magnate Gina Reinhart and Jewish recycling king Anthony Pratt.[B14]Rich List 2020, Australian Financial Review. Retrieved from https://www.afr.com/rich-list His Russian-Jewish family arrived in Australia via China after the war, and Triguboff founded Meriton in the late 1960s after dabbling in construction work for new flats. As rates of migration surged, Triguboff set about expanding Sydney upwards and early flats gave way to soaring apartment towers when the company hit its stride in the 1990s. By the twenty-first century, Meriton’s towers held the titles for the tallest residential buildings in Sydney and Brisbane.

The first large developer to expand high-rise towers westwards beyond Sydney’s harborside suburbs, Meriton’s commanding presence in the Sydney property market has not endeared it to critics who see Meriton’s “low-cost, high density” formula for apartments as a blight on Sydney’s urban landscape. Meriton’s tower developments were responsible for much of the tightening of Sydney’s planning laws during the Carr state government. The resulting SEPP 65 law, passed in 2002, introduced mandatory design standards for apartment developments, and allowed only registered architects to design towers.

Over the years, Triguboff has allocated vast sums of his personal fortune to Jewish causes in Israel, where his parents relocated to. From funding schools to promote Bedouin assimilation, to the Shorashim project, a Rabbinical initiative dedicated to assisting Jews in proving their Jewish heritage when migrating to Israel, Triguboff’s Zionist credentials are impeccable. In 2012, the Harry Triguboff Gardens at the Rabin Centre, a library and research center in Tel Aviv, was dedicated to him for his long-term support for the Jewish National Fund,[B15]‘Triguboff Gardens Dedicated at Yitzhak Rabin Center in Tel Aviv’, KKL-JNF, 9 September 2012, retrieved from https://www.kkl-jnf.org/about-kkl-jnf/green-israel-n...boff/. an organization founded to settle and irrigate former Palestinian land. Not limited to Israeli causes, Triguboff is also a major donor to the Chabad education movement in Australia, worrying that Jewry might disappear without Jewish schooling. Triguboff’s comments on the future of the Jewish people to the newspaper The Jerusalem Post in 2013, highlight his concerns about the demographic future of the diaspora:

Diaspora Jewry would disappear, that’s why I was always very much involved with school. I wanted Jewish children to go to Jewish schools. I realized that we have to do everything we can to preserve the Jewish race. I’m very proud of it and I think it’s wonderful.[B16]I. Evyatar, ‘Spotlight: Building Jewish Identities’, Jerusalem Post, 4 July 2013, retrieved from https://www.jpost.com/features/front-lines/spotlight...318797

Triguboff’s feelings on the people and composition of Australia are arguably less devoted. Commenting on a government proposal in 2006 for a values and language test for new migrants to Australia, Triguboff put it bluntly: “What’s more important for me—a guy who can fix my tap or a guy who can speak English?”[B17]A. Cennell, ‘Triguboff: Let’s Trade Trees for Homes’, Sydney Morning Herald, 11 October 2006, retrieved from https://www.smh.com.au/national/triguboff-lets-trade...v.html

Not surprisingly given the large migrant source of new apartment purchasers, Triguboff is a staunch supporter of “Big Australia,” having the ear of many NSW governments, and he hopes that not only are current population targets well exceeded, but that Australia’s population will quadruple to reach 100 million[B18]‘Population to hit 50 Million by 2050: Triguboff’, Sydney Morning Herald, 25 January 2020, retrieved from https://www.smh.com.au/national/population-to-hit-55...5.html—a proposal that, given the current source of most migrants to Australia and declining White birth rates, would lead to the effective eradication of Australia as a predominantly White country. What Triguboff, the preservationist of the Jewish race, would think of a proposal by a gentile property developer to quadruple the population of Israel, primarily through mass immigration of non-Jews and purely for his own economic gain, need not even be asked.

Mirvac

Formed later than Meriton and Stockland, Mirvac emerged from the economic crash of the 1970’s and remains one of the largest property developers in Australia. Publicly listed since 1987, Mirvac’s apartment tower projects are prominent in all major cities of the country. Founded by Jewish architect and developer Henry Pollack (born Polak), Pollack remained chairman and a major shareholder of the company until his retirement in 1996 and continued his architectural practice with Mirvac’s in-house architectural team. Born in 1922 in Lodz to Russian-Jewish parents, Pollack fled to Lithuania ahead of the advance of the German Army into Poland. Arriving in Sydney in December 1941 via China, Pollack married a local Jewish girl and jumped from career to career, holding jobs as a watchmaker, farmer, and owner of a women’s fashion store. Pollack finally found his calling in architecture after a visit to the Brussels World Exhibition in 1958; he became attracted to modernism and was bristling with a desire to break with the past:

Seeing the Brussels Exhibition … made me realise that I could join a revolutionary movement and build the future, disregarding the phlegmatic, plodding past which started with Greek columns in the sixth century BC and was still using them in twentieth AD.[B19]H. Pollack 2001, The Accidental Developer, The Fascinating Rise to the Top of Mirvac Founder Henry Pollack, ABC Books, Sydney, p.193.

Predictably, the reasons invoked for this rejection of traditional western architecture are to be laid at the foot of Hitler and the Holocaust:

Watching the light and airy structures of the Brussels Exhibition, totally different from the buildings I knew, I wondered whether it was a coincidence that Hitler banished the Bauhaus and proscribed modern architecture and art. Could his murderous decisions be taken in full daylight behind clear glass walls? Modern architecture had cut all ties with the past, made the previous architectural styles irrelevant and seldom referred to them. I felt the same way; I wanted to start afresh and not be associated with continuity. I did not want a profession that had grown out of the unbearable past.[B20]Ibid., p.195.

(H. Pollack 2001, The Accidental Developer, The Fascinating Rise to the Top of Mirvac Founder Henry Pollack, ABC Books, Sydney, p.193.)

Pollak began his career in the office of architect Henry Kurzer and opened his own practice in 1964. Early commissions for houses ensued, but Pollack, now in his 40s and worried about the viability of his late-chosen profession, began to seek out his own development sites to become self-reliant. His first projects as an architect/developer—blocks of flats in Lakemba in Western Sydney and Roscoe Street, Bondi—sold well and Pollack soon had numerous flat projects throughout Sydney. Among the larger projects of Pollack’s pre-Mirvac days was a 14-story block of flats, High Tor at 20–24 Rangers Road, Neutral Bay and a sprawling lot of low-rise flats at 102 St Georges Cres, Drummoyne, projects by now financed through venture partnerships, often with other Jews.[B21]Ibid., p.241.

(H. Pollack 2001, The Accidental Developer, The Fascinating Rise to the Top of Mirvac Founder Henry Pollack, ABC Books, Sydney, p.193.)

Pollack’s success attracted the attention of others, and an offer of financial partnership came from the Australian Guarantee Corporation, a finance group owned by the Westpac Bank. The partnership was christened with the company name “Mirvac” in 1972. Mirvac transitioned from flat renovations during the economic downturn to high-rise towers—a 21-story tower at 80 Berry Street, North Sydney an early project—and other high-rise apartment towers in the then emerging Bondi Junction, Chatswood and North Sydney precincts soon followed. Driven by a more holistic development style than competitors like Meriton, from its inception Mirvac has distinguished itself with an up-market focus to its apartments, a luxury tower at 5 York Street in central Sydney (built in 1981) being an early example. Seemingly a focal point of Sydney’s Jewish property developers, Pollack also took part in the development of Shalom College, appointed by primary donor Frank Theeman as the architect of the complex,[B22]According to Pollack, Theeman abandoned his involvement in the project upon being told it would not earn him a knighthood, Ibid., p. 234.

(H. Pollack 2001, The Accidental Developer, The Fascinating Rise to the Top of Mirvac Founder Henry Pollack, ABC Books, Sydney, p.193.) and Jews have remained at the helm of Mirvac into the present, with current CEO and managing director Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz being appointed in 2012. In 2020, she was ranked number 2 in the Australian Financial Reviews property power players, ahead of Darren Steinberg, the CEO of investment property trust Dexus.[B23]N. Lenaghan, ‘New kids on the block join 2020’s property power players’, Australian Financial Review, 1 October 2020, retrieved from https://www.afr.com/property/commercial/new-kids-on-...55n6f.

Frank Theeman and the Green Bans

Born Franz Thiemann in Vienna in 1913, Theeman left Austria with his wife and arrived in Sydney in 1939 where he started a successful hosiery business, Osti Pty Ltd.[B24]G. N. Hawker 2012, ‘Theeman, Frank William (1913—1989)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Retrieved from https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/theeman-frank-william–15666 Theeman saw the opportunities in property under the development-friendly Askin government and began purchasing vast swathes of terraced houses along Victoria Street near Kings Cross. The properties on Victoria Street formed part of the Woolloomooloo Redevelopment Central Plan (1969), intended by the NSW state government as a new high-density precinct to replace a working-class suburb. Other Jewish developers also followed suit; Frank Lowy’s Westfield Towers on William Street was an early start, and Parkes Developments had plans for a tower over King Cross Station, while Sid Londish snatched up 9.5 acres of property in Woolloomooloo, with plans for towers to be erected over the next 30 years.[B25]Shirley Fitzgerald 2008, ‘Woolloomooloo’, Dictionary of Sydney, retrieved from https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/woolloomooloo Theeman’s project at 55–115 Victoria Street, comprising three 45-story residential behemoths and a 15-story office tower, would have razed the historic streetscape to the ground and have dwarfed the surrounding buildings. His project instantly aroused local and much more powerful opposition, sparking one of the most controversial incidents in Australian property and criminal history.

The “Green Bans” as they came to be known, were union strike actions imposed on developments by the Builders Laborers Federation (BLF), led by Jack Mundey. Mundey, a Communist Party member, allied his union base with the middle class in a campaign to save historic Sydney sites of architectural and environmental value from redevelopment. Responding to calls from local residents aggrieved by development plans in their nneighborhood, the BLF placed Green Bans over projects, barring any union worker from participating and effectively halting construction work. The 42 Green Bans imposed in Sydney by the mid-1970s ranged from parks to expressways and high-rise towers,[B26]See Green Bans 1971-1974, retrieved from https://www.greenbans.net.au/green-bans-1971-74 and in July 1973 a Green Ban was placed over Theeman’s sites on Victoria Street after local opposition, including from Victoria Street resident Juanita Nielsen, who prominently railed against Theeman’s development in the pages of her local newspaper. As a newcomer to the property development industry, the Green Ban over his project cost Theeman substantially, since he was paying an estimated $16,800 a week on interest payments for the loan by 1975.[B27]G. N. Hawker, op. cit. The stalemate drew on, and residents of Victoria Street opposing the development found themselves confronted by Sydney’s criminal underbelly. Inhabitants and squatters of the now Theeman-owned houses were intimidated by thugs alleged to have been in the pay of Theeman and violently evicted, and the head of the local anti-development group was kidnapped and terrorised into abandoning the protest. The fate of Theeman’s leading opponent, Juanita Nielsen, was the least pleasant:

On the morning of July 4, 1975, Nielsen opened the door of the Carousel Club in Kings Cross—owned by Abraham Gilbert Saffron, a man often referred to by Sydney’s racy afternoon papers as “Mr Sin.” She was supposed to be meeting a man at the club to discuss placing some ads in her paper but was never seen again.[B28]

An inquest and successive attempts to uncover the story behind Nielsen’s disappearance and presumed murder have come up empty. The case is now infamous in Sydney crime history; newspaper articles and books speculating on her disappearance continue to be published to this day. Abe Saffron is alleged to have loaned money to Theeman to fund his project, but Theeman denied having any role in Nielsen’s disappearance and little more than allegations were ever laid at his feet during his later life. Eventually the Green Ban was lifted and a smaller 15-story development was completed instead, one that left the Victoria Street streetscape largely intact, punctuated now only by minor apartment blocks like 145 Victoria, designed by Jewish architects Henry Kurzer and Henry Haber. The efforts of the BLF saved the Woolloomooloo precinct and countless other areas throughout Sydney from high-rise redevelopment, and it has persisted as a low-density historic suburb of Sydney to this day.

The Reign of Seidler

The contribution of Jewish architects to the new era of flats and apartments in Sydney bring forth the names of Hugo Stossel of H. Stossel and Associates from Hungary, another leading designer of flats and towers, the firm Lipson and Kaad, and other names, such as Stephen Javor, Alexander Kann, Hans Peter Oser, Ervin Mahrer, Aaron Bolot and Henry Epstein—all again overshadowing gentiles in the growing flat and high-rise industry. Highlights from Aaron Bolot from Russia include the Wylde Street Cooperative Apartments built in Potts Point in 1950, a striking early modernist design that has attained a similar place in architectural annals to Stanhill in Melbourne, and the 12-story Quarterdeck Apartments in Carabella Street, Kirribilli, another early tower by Lend Lease (built in 1960) which demolished the historic home of Australia’s first prime minister Edmund Barton. With these Jewish architects, the earlier Art Deco and Spanish Mission Style used for the design of inter-war flats was driven out in favor of Modernism and the International Style. None of these names however come close in fame and recognition awarded to Australia’s most famous Modernist architect, if not the most famous Australian architect since 1945, Harry Seidler, a major proponent of high-density living whose concrete towers would come to define the skyline of Australian cities.

Born to a Jewish family in Vienna in 1923, Seidler spent time as an enemy alien in a British internment camp, leaving Austria in 1938. Seidler studied under Marcel Breuer and Walter Gropius in New York at the Harvard Design School and, after forays in New York and South America, he was persuaded by his parents to design their new Sydney home, whereupon he decided to stay. Finding early work designing controversial modernist houses, more often than not for migrant Jewish clients, Seidler designed countless blocks of flats, iconic examples including Ithaca Gardens and Vaucluse Waters, and transitioned into larger and larger projects, utilising new prefabricated concrete techniques. Seidler was conscious of the existing prejudice against flats, which he attributed to the low-quality architectural styles of existing flats built by developers like Parkes, and he set out with a desire to shift Sydney away from suburbia to high-rise “Wohnmaschinen”[B29]“Living-machines.” consistent with his Bauhaus training.

Seidler teamed up with Meriton and other developers later in life, but he is most notable for his partnership with Lend Lease founder, Gerardus “Dick” Dusseldorp, with whom he collaborated on Sydney’s soaring new towers, designed true to the Modernist ideal: concrete boxes to work in and glass and concrete boxes to live in. A gentile migrant from the Netherlands, Dusseldorp’s background in many ways mirrors the story of the post-war Jewish migrants. Born in Utrecht in 1918, Dusseldorp was conscripted into forced labor by Germany during World War II, spending time in labor camps in occupied Poland, and arrived in Australia in 1951, directed by the Dutch building company he worked for to find new development opportunities away from war-torn Europe. Like Seidler and other Jewish developers and architects, his foreign upbringing similarly lent him an unfamiliarity with the cultural mores of Australia and a worldly mindset that manifested itself as a dislike of the parochial nature of 1950s Sydney. His construction company Civic and Civic, later growing into the multinational developer Lend Lease, would become yet another pioneer of high-rise residential and office towers in Sydney, and it was Dusseldorp and his company who drafted the bill and spearheaded the effort to introduce Strata Title reform in New South Wales, via the Conveyancing (Strata Titles) Act of 1961.[B30]Thompson 1986, op. cit., p.123-137.

The consistent lobbying effort of both Seidler and Dusseldorp was also successful in removing the old 12-story height limit in the central city,[B31]E. Farrelly 2021, Killing Sydney – The Fight for a City’s Soul, Pan Macmillan Australia, p.36. replacing it with a generous floor space ratio (FSR) that allowed much taller towers to proliferate, ultimately transforming the traditional form of Sydney’s central business district. Together they produced Sydney’s landmark modernist towers—Australia Square, MLC Centre, Capita Centre, and Blues Point Tower. Perhaps Australia’s ugliest apartment tower, Blues Point occupies prime Sydney real-estate, situated on the edge of a peninsula opposite the harbour bridge, a blight on the landscape for all to see. Blues Point was the only tower built in the failed McMahons Point redevelopment, which proposed 29 towers across the peninsula. Seidler defended his work in classic Seidler style, berating Blues Points critics as “illiterate, insensitive, and uneducated.”

Seidler’s disparaging views about the Australia he arrived in, the harsh rhetoric against his critics, and his battles with local councils over his outlandish modernist designs have become almost architectural folklore:

Each new project resulted in a fight with councils filled with people Seidler disparaged, variously, as ‘butchers and grocers’ who made ‘idiotic judgments’ on aesthetics and couldn’t read sophisticated plans.[B33]J. Power, ‘Harry Seidler, the ‘great disruptor’ of modern Australian architecture’, Sydney Morning Herald, 11 January 2021, retrieved from https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/harry-seidler-th...m.html

Once describing the Australian architectural scene as a “backwater, a provincial dump,”[B34]‘When Harry met Sydney’, Sydney Morning Herald, 10 March 2006, retrieved from https://www.smh.com.au/national/when-harry-met-sydne...9.html Seidler’s snobbery and disdain for anything traditionally Australian extended to believing that nothing ever built in Australia was worth a heritage listing.[B35]Farrelly, op. cit., p.220. To make way for the MLC centre, the century-and-a-half old Theatre Royal and the Australia Hotel were razed to the ground in one of Sydney’s worst heritage crimes, and Seidler once called for the demolition of Sydney’s iconic Queen Victoria Building, calling it “an architectural monstrosity, a wasteful, stupid building.”[B36]‘Tear down this City Horror’, The Daily Mirror, 26 September 1961, retrieved from https://fabsydneyflashbacks.blogspot.com/2021/09/196...n.html Siedler, like Graf and Pollack, was critical of walk-up flats, seeing the trend as a poor urban outcome and more often than not devoid of architectural quality. But this opposition ran counter to the direction of mainstream Australian sentiment, seeing the solution to the walk-up problem as promoting even higher densities, rather than restricting flats.

Conclusion

Parkes Developments and Progress and Properties may have disappeared, but Harry Triguboff’s Meriton still rules the roost in Sydney apartment developments, a role supplemented by a property development elite who leverage a large influence on the NSW political scene through lobbying groups such as the prominent Urban Taskforce or the Property Council of Australia. With a high proportion of Lebanese and Chinese, as well as Jewish players, this developer elite is marked by a meagre presence of individuals descended from Australia’s founding stock. Not much has changed in the reputation of property developers in Sydney since the years of the alleged collusion of Paul Strasser and the Askin government in the 1970s, as they continue to be plagued with regular occurrences of corruption and scandal. Land transactions are a common target for official investigation into corrupt dealings with local councils or the state government. Property developers have been banned from donating to NSW political parties since 2009 but have found plenty of other measures for the plundering of Australia’s cities and livelihood. Chief among these is the promotion of mass immigration, a policy consistently advocated for by the Urban Taskforce in the face of all evidence of its crippling effect on Australia’s GDP per capita, let alone on its culture and demographic makeup. The Taskforce continues to push for a “rapid return” of Australia’s extraordinarily high migrant intake program in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.[B37]‘Developer Lobby demands “rapid return” of mass immigration, Macrobusiness, 21 September 2021, retrieved from https://www.macrobusiness.com.au/2021/09/developers-...ation/ Comprising 10 members, Lebanese and Jewish members easily outnumber the White Australians on the Executive Committee of the Urban Taskforce[B38]See Urban Taskforce Executive Committee, retrieved from https://www.urbantaskforce.com.au/about-us/urban-tas...ittee/, leaving little wonder why this group, so unrepresentative of Australia’s demographics, is so hostile to the continuation of the Australian people as a cohesive entity.

The Un-Australian Dream

From South Coast to Miami Beach.

Further afield from Sydney and Melbourne where the majority of Jews reside, Jewish property developers are also notable on the Gold Coast, performing a now familiar role. It was here that property developers Stanley Korman (encountered previously in Melbourne) and Eddie Kornhauser made a name for themselves, not just as pioneers of high-rise living, but of the Gold Coast as a city itself. Once little more than a beachside town in an area called South Coast, these early investments laid the groundwork for the 1980s tourist boom, when the city became awash with Japanese money and holiday travelers, and the skyline grew ever taller with a sheer wall of apartment towers now settled along the beachfront. It was Stanley Korman, the “father of the Gold Coast,” who was among the first to see the potential of the area, developing the 10-story Kinkabool tower at 34 Hanlan Street in 1960, the first apartment tower on the Gold Coast, which at the time towered above mere beachside shacks. Korman, inspired by a holiday in the USA,[C1]P. Spearritt & J. Young 2007, ‘Korman, Stanley (1904-1988)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, retrieved from https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/korman-stanley-12755 began his pioneering beachside venture in the late 1950s with an American-style holiday resort (the Chevron Hotel) as well as the Chevron and Paradise Islands housing precincts, leading the way in establishing Surfers Paradise as a popular holiday destination:

He [Korman] was soon generating much of the impetus for the phenomenal development of the locality from ‘just another tourist resort’ to an internationally recognised location.[C2]K. Moore 2005, ‘Embracing the Make-believe—The Making of Surfers Paradise’, Australian Studies, 18(1), p.187-210, p.195.

Born in Poland, the Korman brothers Stanley and Paul arrived in Australia in 1932 and set up a hosiery business, migrating into property development after the war; they transferred their focus to the Gold Coast after developing Stanhill and other American-style hotels in Melbourne. Stanley Korman’s brash style and sprawling network of companies would ultimately attract the attention of the government, and he was charged and sentenced to six months prison for issuing a false shareholder prospectus, later leaving Australia for the USA in 1967.