In this essay I examine the effects of Jewish immigration on the native English in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, focusing mainly on the East End of London and drawing entirely on the work of Jewish historians.

Areas of concentration

While wealthier Jews typically lived in the West End or in country houses, poorer Jewish immigrants before 1881 had tended to converge on the East End. Those who came from 1881 onwards joined them and, as their numbers grew, they took over whole streets, then larger areas. Susan Tananbaum cites estimates of the Jewish population of London that range from 150,000 to 180,000, of whom about 100,000 lived in the East End.[1]Jewish Immigrants in London, 1880-1939, Susan Tananbaum, 2014, p26 Lloyd Gartner cites higher estimates. In 1901, in the Borough of Stepney alone, he says there were nearly 120,000 Jewish residents, about 40% of its population, making it the borough of most intense immigrant concentration.[2]The Jewish Immigrant in England, 1870-1914, Lloyd Gartner, 1973, p171-2 As Geoffrey Alderman describes,

“Stepney included the areas of Whitechapel, St George’s-in-the-East, and Mile End, in which Jews had traditionally lived adjacent to the City of London, and into which the immigrants now poured just as their more prosperous English-born or Anglicized co-religionists were migrating northwards. According to the census of 1881, over three-quarters of the Russians and Poles (most of whom can be assumed to have been Jews, of course) who lived in London were located in these areas; by 1901 the proportion was just under 80 per cent. By 1901 the alien population of Whitechapel had reached almost 32 per cent; in Mile End Old Town it was nearly 29 per cent.”[3]Modern British Jewry, Geoffrey Alderman, 1992, p118-9. ‘Alien’ referred to those who had immigrated, not been born in Britain.

In 1899, a map of “Jewish East London” was included in The Jew in London, a study “published under the auspices of Toynbee Hall”; the map showed that “some streets north and south of the Commercial and Whitechapel Roads were almost entirely Jewish by residence”. The study stated that

“The area covered by the Jewish quarter is extending its limits every year. Overflowing the boundaries of Whitechapel, they are spreading northward and eastward into Bethnal Green and Mile End, and southward into St. George’s-in-the-East; while further away in Hackney and Shoreditch to the north, and Stepney, Limehouse and Bow to the east, a rather more prosperous and less foreign element has established itself. . . . Dirt, overcrowding, industry and sobriety may be set down as the most conspicuous features of these foreign settlements. In many cases they have completely transformed the character of the neighbourhood.”[4]Modern British Jewry, Alderman, p118-9. Toynbee Hall was a settlement house on Commercial Road that inspired similar ventures in the USA; it continues to operate today amid a primarily Bangladeshi population.

As Gartner describes,

“There were two spines to eastward Jewish expansion in the East End. One was Whitechapel Road (Aldgate High Street and Mile End Road at its eastern and western ends), a street of Roman origin moving east and slightly north, and the second was Commercial Road, which was hacked through courts and alleys in the mid-nineteenth century to connect the City with the docks and stretching south-east. Both slowly filled with Jewish businesses and residences. The streets branching off them were slowly infiltrated in their turn, and presently the little side turnings were also annexed into the Jewish quarter. By about 1910 the Jewish area reached its furthest extent, with the fringe of the City symbolized by Aldgate Pump as western limit, and with Cable Street to the south, the Great Eastern tracks on the northern edge, and a flexible eastern limit around Jubilee Street, Jamaica Street, and Stepney Green as its informal boundaries.

These two square miles enclosed some of the most densely populated acres in England. This was caused not only by normal overcrowding of large families and the presence of many lodgers, but was aggravated by the razing of thousands of dwellings to make room for railway facilities, street improvements, business premises, and schools. Little or no provision was made for the displaced inhabitants, who usually remained in the vicinity where they earned their livelihoods and jammed the remaining houses still further. Although wholesale demolitions for commercial purposes subsided after 1880, they continued at quite a rapid pace for such public improvements as schools and slum clearance. In other words, Jewish immigration intensified the East End’s deep-rooted problem of house accommodation by preventing the population from declining as its houses were pulled down.”[5]Gartner, p146-7

My last essay mentioned the reception of new immigrant Jews among those longer-established in England. It became “an anxiously desired goal of native Jewish efforts among immigrants … to lure them out of the East End and to disperse them among the smaller cities in the provinces.”[6]Gartner, p148 Yet,

“Up north in Grimsby, Joel Elijah Rabinowitz retorted that the Jewish immigrant would continue to choose the London slum in spite of every inducement, because employment and fellow-Jews were to be found there. The Russo-Jewish Committee, which tried earnestly to persuade immigrants to settle away from the East End, realistically explained why the immigrants persistently ignored these blandishments:

(1) Indisposition on the part of the individual refugee to migrate to quarters where he would be mainly among strangers.

(2) Local prejudices against foreigners, and especially against refugee Jews, who are regarded as interlopers.

(3) The persistent objection of some of the refugees to obtaining a knowledge of English.

(4) The objection to the schooling of the children outside Jewish influences.”[7]Gartner, p149

As in most times and places, immigrants congregated for the sake of familiarity, security and mutual support. They were from all over Eastern Europe, but Judaism and the Jewish identity bound them to one another and separated them from the English, other than geographically. Their growth in the East End was rapid and contiguous, and they became dominant over ever more territory until the numbers arriving subsided. The immigrants also intensified demand for housing and, as also seems perennial, they benefited landlords at the expense of renters, as Alderman describes:

“Inevitably, the housing shortage resulted in the raising of rents; in London as a whole rents rose between 10 and 12 per cent in the period 1880-1900, but in the East London boroughs the rise was of the order of 25 per cent. Prospective tenants might also find themselves asked to pay ‘key money’ (often dubbed ‘blood money’) to the landlord or the outgoing tenant, merely for the privilege of moving in.”[8]Modern British Jewry, Alderman, p126

He continues:

“That Jewish landlords were more likely than native landlords to raise rents was a fact of life; that the rents they raised were usually those of their brethren from eastern Europe was merely a plea in mitigation. The Jewish influx caused rents to rise; had it not been for the Jews, rents would either not have risen or would not have risen so much. It is also true that the clearance of slums, and their replacement by model dwellings, ensured housing for Jews at the expense of non-Jews.”[9]Modern British Jewry, Alderman, p129-30. He adds that “Perhaps for this reason Samuel Montagu insisted, in making a gift of £10,000 to the LCC in 1902, that the special housing complex for Whitechapel residents which the money was used to build on the Council’s White Hart Lane estate, Tottenham, should be available ‘without distinction of race or creed’.” Montagu was of the older, wealthy Jewish ‘Cousinhood’ and worked for Jews to integrate into British society without losing their religion. Members of the Cohen, Rothschild and Henriques families took a similar view.]

Gartner’s more critical description pierces the blandness of aggregated and averaged statistics. He says that Jews seemed willing to pay higher rents which accelerated “the displacement of English tenants”.

“By a process of mutual cause and effect, the high rents paid by Jews invited overcrowding, which in turn further stimulated rack-renting. Nothing hindered a landlord from raising rents as he pleased or from expelling any tenant to make way for anyone whom he pleased. Matters did not improve when, as sometimes happened, the landlord was himself a Jewish immigrant. (Real estate in Jewish districts was a favoured investment for immigrants who prospered.) … [R]ents probably rose fifty per cent or sixty per cent when a street turned Jewish, with the entire difference pocketed by speculating or rack-renting landlords and partially made back by tenants who took in lodgers.”

Taking in lodgers could only exacerbate the crowding. The growth of the Jewish dominion was inexorable. Gartner continues:

“The Jews’ alien status and the higher rents which accompanied them incited severe hostility when they settled in a new street as the Jewish quarter gradually spread out. Sensing that they would soon be submerged, some of the English and Irish inhabitants moved out at once. Others remained behind to give vent to cold or hot hostility, whether by calculated snubbing or, at times, by stones thrown or windows broken. But they too presently evacuated.”[10]Gartner, p157-8

The standard of life was diminished in other ways. According to Gartner,

“To an East End which was water-starved sometimes, unsatisfactorily inspected by public authorities, and overcrowded in decrepit or poorly built houses, the Jews brought not only an extra measure of overcrowding but a seeming ignorance and indifference to sanitary requirements. Accumulated and uncollected refuse lay in rotting piles inside and outside houses, while the interiors were often dank and malodorous from foul water closets, leaking ceilings, untrapped sinks, and cracked, moist walls.”[11]Gartner, p152

A writer in the Jewish Chronicle remarked in 1880 that “[o]f the Jewish poor in the Metropolis it is probable that ninety per cent are Russians. They have the Russian habit of living in dirt, and of not being offended at unsavoury smells and a general appearance of squalor.”[12]Jewish Chronicle, 1st October 1880, in Tananbaum, p23-4 The Lancet stated that

“the presence in our midst of this numerous colony of foreign Jews gives rise to a sanitary problem of a most complicated nature. Their uncleanly habits and ignorance of English ways of living render it difficult to maintain in a wholesome condition even those more modern dwellings where the system of drainage is well organised.”[13]Tananbaum, p34

According to Tananbaum, the socialist activist Beatrice Potter (later Beatrice Webb), who investigated the conditions of life in the East End, found that

“the Jewish ‘race’ could withstand ‘an indefinitely low standard of life’. Their working lives were characterized by ‘long and irregular hours, periods of strain, and periods of idleness, scanty nourishment, dirt and overcrowding, casual charity — all conditions which ruin the Anglo-Saxon and Irish inhabitant of the East End [yet] seem to leave unhurt the moral and physical fibre of the Jew’.”[14]Tananbaum, p30. She continues: “Many descriptions of East End Jews emphasized racially unique characteristics, and connected it to Jews’ clannishness, commercial skills and disturbing competitive nature.”

Nathaniel Rothschild, the first Baron Rothschild, acknowledged in 1904 that “it is unfortunately true that a large number of them [Jewish immigrants] live in the Borough of Stepney… [and] that the rooms are insanitary, that more people live in a room than ought to be’.”[15]Tananbaum, p30

Even the cleanest of people could not have entirely surmounted the challenges of the excessive density of people. As Tananbaum describes,

“Rose Henriques, of the Oxford and St George’s Jewish (later Bernhard Baron) Settlement, described the housing as ‘dreadful … [with] staircases that stank’. ‘The tragedy was that the smells didn’t necessarily mean that the tenants were dirty people, although often they were’. Even with ‘incessant cleaning’, buildings ‘stank of generations of overcrowded bodies and of outer clothing that become odorous from long use’.”

Stepney only gained a reliable water supply in 1902, and “[a]s late as 1939, 90 per cent of Stepney’s homes lacked baths.”[16]Tananbaum, p34 Gartner remarks of Jewish migrants in general that their movement from towns and villages into metropolitan centres had the “immediately visible result” of “a rather foul slum zone and a knotty problem of health and housing. … The physical problems of the Jewish quarters did not vanish until the areas were torn down (or, as in London, bombed out) or the Jews abandoned them.”[17]Gartner, p180-1

Working from home

Insanitary conditions were typically accompanied by noise from home life and home-based work. Immigrants were more inclined to adapt the environment to themselves than the reverse. According to Gartner, “England was a factory country, and very few immigrants had ever worked in a factory. They had worked in little workshops back in Russia and Poland, and that is where they continued to work in England.”[18]Gartner, p57 In Stepney in 1901,

“Many living quarters doubled as workshops, with hundreds of contractors working out of their homes. By day, food, garments and refuse collected in the kitchen. At night, members of the household used the room to sleep. Lily Montagu, the famed warden of the West Central Settlement, contended that overcrowded homes ‘limited the outward realisation of the joys of family life. In tenement dwellings … every corner of the home is utilised for some domestic or industrial purpose … Excepting during the hours of sleeping and feeding, most scenes of family life are enacted in the streets’.”[19]Tananbaum, p31

According to a London County Councillor speaking to the Royal Commission on Alien Immigration, a Jew in the East End “will use his yard for something. He will store rags there, perhaps—mountains of smelling rags, until the neighbours all round get into a most terrible state over it, or perhaps he will start a little factory in the yard, and carry on a hammering noise all night, and then he will throw out a lot of waste stuff, offal, or anything like that—it is all pitched out, and in the evening the women and girls sit out on the pavement and make a joyful noise . . . on the Sunday the place is very different to what the English are accustomed to.”[20]Gartner, p157-8 In Todd Endelman’s words, “the aliens worked on Sundays, slept outside on hot summer nights, ate herring and black bread, and read Yiddish newspapers.”[21]The Jews of Britain, 1656 to 2000, Todd Endelman, 2002, p158 Jews working and trading on Sundays became a point of particularly fierce contention.

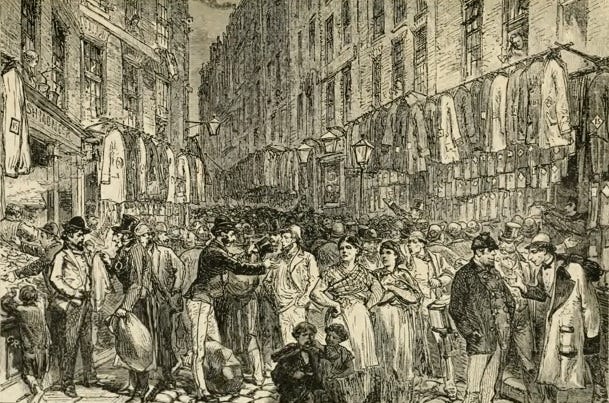

Immigration alienated the native people. Areas that became Jewish-dominated acquired an “aura of exotic strangeness” which “provoked indignation and unease”.[22]Gartner, p180-1 and Endelman, p158. Gartner: “Street life in the East End and the other Jewish quarters, a sort of common denominator, displayed a vividness which fascinated many outsiders although it offended the more staid native Jewish and Gentile residents. Store signs, theatrical placards, bookshops, bearded types from the old country, immigrant women wrapped in vast kerchiefs, all conferred an aura of exotic strangeness upon the Jewish area.” Gartner says that “[i]mmigrant Jewry formed a society apart, with standards derived from other sources than England.” Naturally this was so, as “immigrant life was an attempt to preserve with more or less adjustment the social standards and habits of home and communal life in Eastern Europe.”[23]Gartner, p166. He continues: “To a greater extent than other migrants from rural or small town environments to the big city, the Jews maintained much of the outward appearance and even the flavour of their former way of life.” This is still true of Hasidic Jews, as in Stamford Hill. As Todd Endelman describes,

“Residents of the East End and middle class visitors alike viewed immigration as a foreign invasion, turning once-English districts into “little Jerusalems” and “little Palestines.” Native workers felt overrun and displaced as immigrants flooded in and occupied street after street. … [A] witness told the Royal Commission on Alien Immigration in 1903 [that] “the feeling is that there is nothing but the English going out and the Jews coming in.” A local borough councilor complained that as he walked through Mile End or Cable Street he saw that “the good old names of tradesmen have gone, and in their places are foreign names of those who have ousted Englishmen out into the cold.” In Whitechapel, a Christian social worker noted, “the English visitor feels himself one of a subject race in the presence of dominant and overwhelming invaders.”[24]Endelman, p157

Endelman also cites an account of life in East London which saw Jews as having “predatory noses and features”, described them as “alien” and remarked that “[o]ne seems to be in a hostile tribal encampment” which “makes one afraid, not of them personally, but of the obvious tenacity, the leech-like grip, of a people who, one feels in one’s English bones, flourish best on the decay of their hosts, like malignant bacilli in the blood.”[25]Endelman, p200 Certainly there is abundant evidence that Jewish interests diverged from, or were directly opposed to, those of the English and that this was most vividly and punishingly experienced by the people of the East End.

Street life

The prolific, concentrated immigrant population exceeded the available buildings and lived partly on the streets. Gartner says that

“it is difficult to speak of home life in many houses, for with one or more lodgers, several children, and perhaps grandparents and other relatives, every Jewish immigrant household was a cramped place. Eight or nine individuals shared two small rooms, and the ratio was even higher in hundreds of dwellings. Hence a large part of home life was lived out of doors by older folk seated at their doorways, by adolescents in search of fascination and adventure, and by children at play in the courts and alleys.”[26]Gartner, p172

The forms of fascination and adventure ranged from the sublime to the deplorable. Gangs of youths were free to prey on more peaceable folk. As we saw in the last essay, and as Robert Henriques describes, “the Anglo-Jewish community had acknowledged the immigrants as a charge which it had met with comprehensive generosity.” However, their children came to present “a new problem”. Though many “accepted the stringent demands of orthodox Judaism learnt from their parents”, they were formally observant but lacking “faith and piety”. They dispensed with any regard for “moral obligation or the law of the land”.

“Consequently the streets in the slum districts of the East End were filled with gangs of young Jewish boys, who identified Judaism with the empty shell of ultra-orthodox observance, and who spent their evenings lawlessly roaming the streets, creating disturbances, assaulting and robbing licensed stall-holders and becoming a source of great anxiety and trouble to the police.”[27]Sir Robert Waley Cohen, 1877-1952: A Biography, Robert Henriques, 1966, p68-9

The criminality that arose out of the post-1881 immigration owed something to the pre-existing patterns of Jewish occupations. Earlier in the 19th century, according to Endelman,

“Jewish poverty went hand in hand with crime, squalid surroundings, low-status trades, and coarse behavior. In the 1810s and 1820s, there was a marked increase in the incidence of Jewish criminal activity in London, if the skyrocketing rate of Jewish convictions at the Old Bailey is any guide.”

After 1830, “the number of Jewish street criminals fell … but Jews remained active in socially marginal occupations—as dealers in battered odds and ends, worn-out clothing, rags and rubbish; as keepers of brothels, wine rooms, saloons, gambling dens, billiard rooms, and sponging houses; as fences, crimps, sheriff’s officers, prizefighters, and prostitutes.”[28]Endelman, p82

Of those families who abided by the law, some parents nevertheless raised their children to be competitive, acquisitive and even deceitful, at least in regard to the goyim. Gartner says that “[t]he foreign heritage continued not only in personal and cultural life but in economic activity as well”.[29]Gartner, p22 Schooling offered opportunities to ascend socio-economically, and he mentions “the consuming eagerness with which Jewish children were sent to school in neighbourhoods where neglect of children and hostility to schooling were rampant”. He cites one schoolmaster who remarked on Jewish children’s “smartness, especially in commercial things”, which exceeded that of Christian children, and said that “‘they have a perfect want of moral sense’ in respect of truthfulness.”[30]Gartner, p230 Moses Angel, long-standing headmaster of the Jews’ Free School, said in 1871 that the parents of his pupils were “the refuse population of the worst parts of Europe,” living “a quasi-dishonourable life”, by which, as Endelman says, “he meant that they were street traders and thus liars and cheats.”[31]Endelman, p85

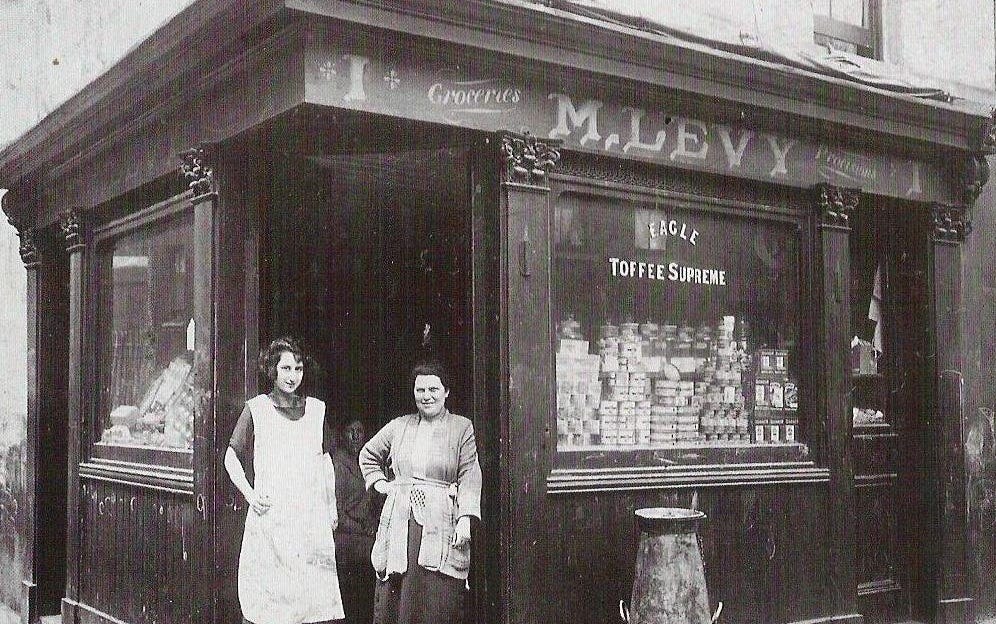

According to Alderman, “[t]he leaders of the Jewish communities in London had their own special reasons for hastening the demise of the Jewish pedlar. The peddling and criminal fraternities interacted in a manner that was both embarrassing and dangerous.”[32]Modern British Jewry, Alderman, p11 Endelman describes how, as the 19th century proceeded, “[t]he expanding native-born middle ranks of English Jewry were filled with the children and grandchildren of peddlers, old clothes men, and market traders who had become respectable, if modest, businessmen.”[33]Endelman, p92. He continues: “A striking illustration of this can be seen in the aforementioned orange trade. As noted, by mid-century, Jews were no longer the dominant group hawking oranges in the streets of London, having been replaced by the Irish. However, they remained prominent at the wholesale end of the trade: the fruit market in Duke’s Place, where street traders purchased oranges and nuts, was entirely Jewish. A similar development occurred in the secondhand clothing trade. Jews increasingly moved out of the lower end of the trade and into its slightly more salubrious branches, becoming pawnbrokers, slopsellers, auctioneers, salesmen with fixed premises, or stallholders in the covered wholesale exchange erected in Houndsditch in 1843. The latter was a bustling international mart, regularly attracting wholesale dealers from France, Belgium, Holland, and Ireland, as well as every city in Britain. A few entrepreneurs then made the leap from slopselling (or slopselling and pawnbroking) into manufacturing inexpensive garments. (Tailoring and shoemaking also served as launching pads for entry into the field.) The two biggest firms in England in the 1830s and 1840s were those of the Moses and Hyam families, both of which grew out of slopselling. Despite the Enlightenment hope that, in the absence of legal barriers, agriculture and the crafts would save the Jews from poverty and make them productive citizens, it was commerce that became the vehicle for the economic transformation of Anglo-Jewry, as it was in all western countries.” Alderman describes areas of later Jewish economic advancement: “Within the metropolis Jewish businessmen expanded in three broad directions. The first was in the manufacture and sale of food products (bread, cakes, dairy products), epitomized in the teashops (of which there were 200 by 1914) of J. Lyons & Co. The second was in publishing partly to serve the needs of the Jewish community but soon catering for national and indeed world markets; notable in this category was the fine art and greetings-card firm of Raphael Tuck, the Levy Lawson family that owned the Daily Telegraph, and Rachel Beer (née Sassoon), proprietor of the Sunday Times between 1893 and 1904. The third was in the distributive trades, especially chemist shops, public houses, restaurants, jewellery, clothing, grocery and furniture stores, to which perhaps the ownership of cinemas and the development of mail‑order companies ought to be added—though these were by no means primarily London‑orientated activities.” Controversy and Crisis, Geoffrey Alderman, 2008, p242.

Commercial conflict

Just as the native people, though far more numerous, were displaced from housing in the East End, so were they from commerce too. Jews as customers tended to buy from Jewish retailers who tended to buy from Jewish wholesalers; evidence of equivalent efforts on the part of the English has gone unfound. Gartner says that

“Securing a foothold was not easy, for the English street-selling trades had long traditions and recognized mores. The Jew had to wedge his barrow into a pitth (place in the street) where an English costermonger might have stood for many years. Bitter were the ‘costers’ complaints that their Jewish competitors grabbed the pitches which they had occupied for many years, did business for unfairly long hours, undersold, and generally disrupted the accepted usages of the trade. The Jews and their defenders replied that the English ‘costers’ merely hated Jews and had always excluded them from their union. … These complaints resounded loudest in Petticoat Lane when that historic London street market situated in the Jewish quarter was taken over by Jewish traders in the 1880’s and 1890’s. … Undeniably, food sellers in Petticoat Lane and their Provincial counterparts lost considerably because the neighbouring Jews did prefer to buy from Jewish dealers.”[34]Gartner, p60-1

British laws and customs were adapted for the sake of the incomers. According to Gartner,

“The greatest friction was caused by the problem of Sabbath observance for, subject to certain limitations upon Sunday hours, the Jews were legally authorized to observe the Jewish instead of the English Sabbath. It was claimed, however, that some Jewish stores and street stalls observed neither day. With the undoubted existence of some such cases as their proof, the beleaguered English tradesmen were convinced that their Jewish rivals were too grasping to keep any day of rest, and thrice-told tales of the Jew supported their views. In the Borough Councils within London, where their influence was strong, the native shopkeepers did all they could to press for stringent Sunday trading ordinances, which would have harmed Jewish tradesmen by denying them enough hours on Sunday to compensate for the hours they were shut on Friday and Saturday.’”[35]Gartner, p62

Yet however strong their influence might have been at the level of borough councils, the English were unable to match “the Jewish authorities” who had already lobbied successfully at the national level for legislation:

“firstly, in two enactments in 1867 permitting workshops which closed on the Jewish Sabbath (roughly sunset Friday to nightfall Saturday) to open late on Saturday evening; secondly, through legislation passed in 1871 allowing Jewish-owned workshops to operate on Sundays provided they had closed during the Sabbath.”[36]Modern British Jewry, Alderman, p9

Beside patronising one another’s businesses, Jews had other means of mutual support. Endelman says that “street traders and itinerant peddlers… routinely obtained goods on credit from Jewish shopkeepers and wholesale merchants” which “allowed penniless immigrants to begin trading on their own soon after their arrival.” Jews also formed friendly societies for mutual aid. These, too, served to benefit their own community and reinforce its separate group identity. “The United Israelites and the Guardians of Faith”, Endelman says, “barred men who cohabited with non-Jewish women or were not married according to Jewish law, while the latter also excluded men who kept their shops open on Saturday mornings and personally attended to business then.”[37]Endelman, p89-90

As one-sided ethnic solidarity did its work, “English tradesmen complained vehemently as their native customers moved away before the tide of foreign Jews, from whom they could expect much less patronage.”[38]Gartner, p62 Jewish shopkeepers prospered and became “the heirs of displaced English shopkeepers in the Judaized streets of the East End, Strangeways and Red Bank, and the Leylands.” Later, between the two world wars, “the aggressive marketing techniques of Jewish shopkeepers—the subtle use of advertising, ‘cut‑price’ offers, and the inducement of ‘loss‑leaders’—caused much friction”.[39]Controversy, Alderman, p242 In Leeds, too, Jewish market stall vendors “were criticised for unfair practices” and were stereotyped as being “responsible for abuses in trades, of engaging in underhand business practices or of sacrificing principle in the pursuit of profit”.[40]Amanda Bergen in Leeds and its Jewish Community edited by Derek Fraser, 2019, chapter 9 The universality of such stereotypes suggests that they were often true, and the English had to imitate such tactics or yield to their unscrupulous competitors; anyone today can see whose approach, and which group, prevailed in the East End and far beyond.

Replacement labour

As workers, Jews tended to have the same inclination to benefit other Jews where possible. As employers, they intended from the start to employ their own kind. As replacement labour, they were a weapon against English workers’ pay and conditions, which smaller-scale immigration had already driven down before the major wave arrived. According to Tony Kushner, after 20,000 Jews settled in the East End in the 1830s amid a local economic depression,

“[t]he only way the clothing trade, boot and shoe trade, and to a lesser degree, the furniture industry could survive was to cut their wage levels so as to compete with provincial and foreign producers. It was to these industries that the immigrants flocked, and the net result was an intensification of the sweating system, and a displacement of native labour by the new arrivals.”[41]British Antisemitism in the Second World War, volume 1, Antony Kushner, 1986, p22-3. “[T]hese industries generally saw a replacement of Gentile with Jewish labour[.]”

When the new arrivals found their conditions intolerable, some went on strike, including cigar makers. Their masters, though of the same tribe, “being unable to procure English workmen … to submit to the lowering of wages, resort[ed] to the practice of travelling to Holland and other parts of the continent, and, exaggerating the state of the cigar trade in England, fill[ed] the poor Dutchmen’s minds with buoyant hopes of high wages.”[42]Modern British Jewry, Alderman, p9. ‘English’ and ‘Dutch’ refer to the legal nationality, not the ethnic group, of the workmen.

Then as now, any supposed need to import workers was really a pretext for employers to benefit themselves by doing so. Gartner says that “in England, still the world’s leading industrial nation, no great new industry or undeveloped region beckoned with opportunities for employment. Moreover, there was already an adequate supply of native and Irish labour for the hard, unskilled jobs.”[43]Gartner, p57 According to Endelman, “[the] stream of new arrivals … guaranteed that wages remained low[.]”[44]Endelman, p135 I have not seen evidence that employers lobbied for open borders in the 19th century, but they may have learned to do so after seeing the effects of Jewish immigration.

Any real demand for Jewish workers arose entirely from Jews who had already arrived. Ethnic solidarity dovetailed with ambitions to outcompete the goyim. As Gartner says,

“The Jewish immigrant workman forewent better hours, superior working conditions, and regularity of employment of an English factory, but also Sabbath work and hostility of the native workers. He preferred to work among his own people, frequently in the employ of an old townsman or a relative.”

An early immigrant from Russia recalled that

“I came to Leeds from Russia in 1852 and was a fugitive from Russian militia men. … We had a place of worship in Back Rockingham Street and I was married there. All of those I remember in my early days came here as single men … It was the usual thing for young fellows when they had settled here to send for Russia for their parents and brothers and sisters and that is how the Jewish people made a home in Leeds.”[45]Derek Fraser in Leeds edited by Fraser, 2019, ch2

As James Appell recounts, “a Kovno master tailor, Moyshe (Morris) Goodman – recognised the opportunity for enrichment in the industry on his arrival in Leeds in 1866, and made numerous trips back to his home city to recruit landsmen for his workshops.”[46]James Appell in Leeds edited by Fraser, 2019, ch4

The employment of illegal immigrants served to undercut even the other Jews who already made use of foreign labour. It also helped to discredit the law and normalise defiance and evasion of the state. As Gartner says, “[t]he Factory Inspector’s right of inspection, tenuous as it was, was further weakened by the reluctance of many Jewish women and girls to admit that they were working illegally. … The inadequacy of the inspecting staff, the limitations of the law, the absence of even a list of workshops, the ruses to evade the Inspector’s visits and queries, all combined practically to nullify English factory legislation in the Jewish workshops.”[47]Gartner, p69-70. Jews continued to arrive illegally at least until the Second World War, with the encouragement of some community leaders.

Demographic change

As the immigrants were given British citizenship and their children grew up, they began to count as voters. Historians have debated the extent to which there was and is a ‘Jewish vote’, but surely all would agree that it is much more real than any ‘white vote’, ‘English vote’ or ‘East-Ender vote’. As the largest and best-organised minority, Jews began to have their way electorally. According to Alderman,

“…the undoubtedly socialist proclivities of the bulk of immigrant Jewry and their offspring… were reflected in and symbolized by such developments as the formation in June 1918 of the Stepney Central Labour Party, the founder and secretary of which was the formidable Romanian-Jewish political strategist, Oscar Tobin; the Labour victory in the Stepney Borough Council elections of November 1919; Labour’s capture of the combined Whitechapel and St George’s parliamentary constituency at the general election of 1922; and even the appearance in the House of Commons, as a result of that same election, of the first Jewish Labour MP, Emanuel Shinwell.”[48]Modern British Jewry, Alderman, p252

Jews did not seize power and territory so much as use the door opened for them by British politicians, who ignored the suffering of the English of the East End and in some cases made a perverse show of gratitude to those who came and exacerbated it. The future saviour of the country distinguished himself by his pro-immigrant sanctimony. According to Gartner, referring to the debates over what became the Aliens Act of 1905,

“[T]he early Labour Party minimized nationalist appeal and scorned racism. … The Liberal Party, especially its Gladstonian traditionalists, regarded free access to England as an unshakable aspect of Free Trade, and were not to be convinced that any harm was incurred by the unobstructed settlement of immigrants. Sir Charles Dilke, most leftward of Liberals, held the general opinion of social reformers that ‘the prohibition of alien immigration is a sham remedy for very grave evils in the labour market’. A younger man who shared the same conviction, C. P. Trevelyan, studied the relation between alien immigration and sweating, and felt ‘thankful to them [aliens] for turning the searchlight of public reprobation on a system which our own people suffer in common with them’. Young Winston Churchill, then M.P. for a considerably Jewish constituency in Manchester, concluded, in common with general sentiment in his Party, that there were not

…any urgent or sufficient reasons, racial or social, for departing from the old tolerant and generous practice of free entry and asylum to which this country has so long adhered and from which it has so greatly gained.”[49]Gartner, p276-7. Churchill was a Tory until 1904, then a Liberal until 1925, then a Tory again. He fought against the Aliens Bill with extreme fervour.

The Tories came to adopt a vaguely immigration-sceptic stance after decades of unprecedented inflow, enough to siphon support from the nativist British Brothers’ League, and far short of even stopping immigration, let alone reversing it. We will elaborate on post-1881 Jews’ impact on politics in a later article.

Clergymen were of no greater help to the English. Endelman notes approvingly that Canon Samuel Barnett, the first warden of Toynbee Hall, a settlement house in Whitechapel, said that “the prejudiced Englishman is apt to call ‘dirty’ whatever is foreign.”[50]Endelman, p158 Like critical theorists later, the esteemed cleric wanted to talk about the ‘discourse around’ dirt and foreignness, not the phenomena themselves, amid which he and his high-born comrades did not have to sleep, make a living and raise children.

Only infrequent comment is passed anywhere in the media or academia to lament the displacement of English East-Enders, whose descendants, typically living in Essex, our rulers despise. Of those who do comment, vagueness is still the norm, as while the area is now occupied by Bangladeshis, most people have some awareness that Jewish immigration set the precedent and that the English were habituated before the Great War to concede their land to foreign colonists.

Nearly everything alien and repulsive about the present foreign occupation of the East End was prefigured by the earlier one. We might ask, in light of the Jewish role in the arrival of the Empire Windrush, whether Bangladeshis first settled in the East End with Jewish encouragement. Perhaps so, or perhaps British governments saw the area as already ransacked and thus no loss if thrown open to barbarians again. Ministers didn’t live there, after all.

References

[1] Jewish Immigrants in London, 1880-1939, Susan Tananbaum, 2014, p26

[2] The Jewish Immigrant in England, 1870-1914, Lloyd Gartner, 1973, p171-2

[3] Modern British Jewry, Geoffrey Alderman, 1992, p118-9. ‘Alien’ referred to those who had immigrated, not been born in Britain.

[4] Modern British Jewry, Alderman, p118-9. Toynbee Hall was a settlement house on Commercial Road that inspired similar ventures in the USA; it continues to operate today amid a primarily Bangladeshi population.

[5] Gartner, p146-7

[6] Gartner, p148

[7] Gartner, p149

[8] Modern British Jewry, Alderman, p126

[9] Modern British Jewry, Alderman, p129-30. He adds that “Perhaps for this reason Samuel Montagu insisted, in making a gift of £10,000 to the LCC in 1902, that the special housing complex for Whitechapel residents which the money was used to build on the Council’s White Hart Lane estate, Tottenham, should be available ‘without distinction of race or creed’.” Montagu was of the older, wealthy Jewish ‘Cousinhood’ and worked for Jews to integrate into British society without losing their religion. Members of the Cohen, Rothschild and Henriques families took a similar view.]

[10] Gartner, p157-8

[11] Gartner, p152

[12] Jewish Chronicle, 1st October 1880, in Tananbaum, p23-4

[13] Tananbaum, p34

[14] Tananbaum, p30. She continues: “Many descriptions of East End Jews emphasized racially unique characteristics, and connected it to Jews’ clannishness, commercial skills and disturbing competitive nature.”

[15] Tananbaum, p30

[16] Tananbaum, p34

[17] Gartner, p180-1

[18] Gartner, p57

[19] Tananbaum, p31

[20] Gartner, p157-8

[21] The Jews of Britain, 1656 to 2000, Todd Endelman, 2002, p158

[22] Gartner, p180-1 and Endelman, p158. Gartner: “Street life in the East End and the other Jewish quarters, a sort of common denominator, displayed a vividness which fascinated many outsiders although it offended the more staid native Jewish and Gentile residents. Store signs, theatrical placards, bookshops, bearded types from the old country, immigrant women wrapped in vast kerchiefs, all conferred an aura of exotic strangeness upon the Jewish area.”

[23] Gartner, p166. He continues: “To a greater extent than other migrants from rural or small town environments to the big city, the Jews maintained much of the outward appearance and even the flavour of their former way of life.” This is still true of Hasidic Jews, as in Stamford Hill.

[24] Endelman, p157

[25] Endelman, p200

[26] Gartner, p172

[27] Sir Robert Waley Cohen, 1877-1952: A Biography, Robert Henriques, 1966, p68-9

[28] Endelman, p82

[29] Gartner, p22

[30] Gartner, p230

[31] Endelman, p85

[32] Modern British Jewry, Alderman, p11

[33] Endelman, p92. He continues: “A striking illustration of this can be seen in the aforementioned orange trade. As noted, by mid-century, Jews were no longer the dominant group hawking oranges in the streets of London, having been replaced by the Irish. However, they remained prominent at the wholesale end of the trade: the fruit market in Duke’s Place, where street traders purchased oranges and nuts, was entirely Jewish. A similar development occurred in the secondhand clothing trade. Jews increasingly moved out of the lower end of the trade and into its slightly more salubrious branches, becoming pawnbrokers, slopsellers, auctioneers, salesmen with fixed premises, or stallholders in the covered wholesale exchange erected in Houndsditch in 1843. The latter was a bustling international mart, regularly attracting wholesale dealers from France, Belgium, Holland, and Ireland, as well as every city in Britain. A few entrepreneurs then made the leap from slopselling (or slopselling and pawnbroking) into manufacturing inexpensive garments. (Tailoring and shoemaking also served as launching pads for entry into the field.) The two biggest firms in England in the 1830s and 1840s were those of the Moses and Hyam families, both of which grew out of slopselling. Despite the Enlightenment hope that, in the absence of legal barriers, agriculture and the crafts would save the Jews from poverty and make them productive citizens, it was commerce that became the vehicle for the economic transformation of Anglo-Jewry, as it was in all western countries.” Alderman describes areas of later Jewish economic advancement: “Within the metropolis Jewish businessmen expanded in three broad directions. The first was in the manufacture and sale of food products (bread, cakes, dairy products), epitomized in the teashops (of which there were 200 by 1914) of J. Lyons & Co. The second was in publishing partly to serve the needs of the Jewish community but soon catering for national and indeed world markets; notable in this category was the fine art and greetings-card firm of Raphael Tuck, the Levy Lawson family that owned the Daily Telegraph, and Rachel Beer (née Sassoon), proprietor of the Sunday Times between 1893 and 1904. The third was in the distributive trades, especially chemist shops, public houses, restaurants, jewellery, clothing, grocery and furniture stores, to which perhaps the ownership of cinemas and the development of mail‑order companies ought to be added—though these were by no means primarily London‑orientated activities.” Controversy and Crisis, Geoffrey Alderman, 2008, p242.

[34] Gartner, p60-1

[35] Gartner, p62

[36] Modern British Jewry, Alderman, p9

[37] Endelman, p89-90

[38] Gartner, p62

[39] Controversy, Alderman, p242

[40] Amanda Bergen in Leeds and its Jewish Community edited by Derek Fraser, 2019, chapter 9

[41] British Antisemitism in the Second World War, volume 1, Antony Kushner, 1986, p22-3. “[T]hese industries generally saw a replacement of Gentile with Jewish labour[.]”

[42] Modern British Jewry, Alderman, p9. ‘English’ and ‘Dutch’ refer to the legal nationality, not the ethnic group, of the workmen.

[43] Gartner, p57

[44] Endelman, p135

[45] Derek Fraser in Leeds edited by Fraser, 2019, ch2

[46] James Appell in Leeds edited by Fraser, 2019, ch4

[47] Gartner, p69-70. Jews continued to arrive illegally at least until the Second World War, with the encouragement of some community leaders.

[48] Modern British Jewry, Alderman, p252

[49] Gartner, p276-7. Churchill was a Tory until 1904, then a Liberal until 1925, then a Tory again. He fought against the Aliens Bill with extreme fervour.

[50] Endelman, p158

RSS

RSS

“As employers, they intended from the start to employ their own kind. As replacement labour, they were a weapon against English workers’ pay and conditions”

There are shills on here that say that the rich don’t import immigrants for the purpose of cheap labor.

These shills are wrong and they know it.

Its simple really. If I hit you its self defense, if you hit me its anti semitism. Now go back to sleep. Morons.

Sleeping or just unorganized?

How many times traveling do we come across people who feel as we do, briefly share anecdotes, then go out own way knowing there’s nothing to be done?

The wolf hunts in packs, the fox roams alone. If whites cannot learn wolf behavior we should figure out why foxes are successful.

Like it or hate it, we don’t take after wolves. The other team does.

The IRON LAW OF THE CAUCASIAN is this:

The more affluent he becomes, the more power he acquires, the more he despises the less affluent, weaker Caucasian, and the more he seeks his destruction.

It seems like they weren’t immediately put on welfare like they would be today. I’d be happy if we could get back to that practice. Let immigrants fend for themselves when they get here.

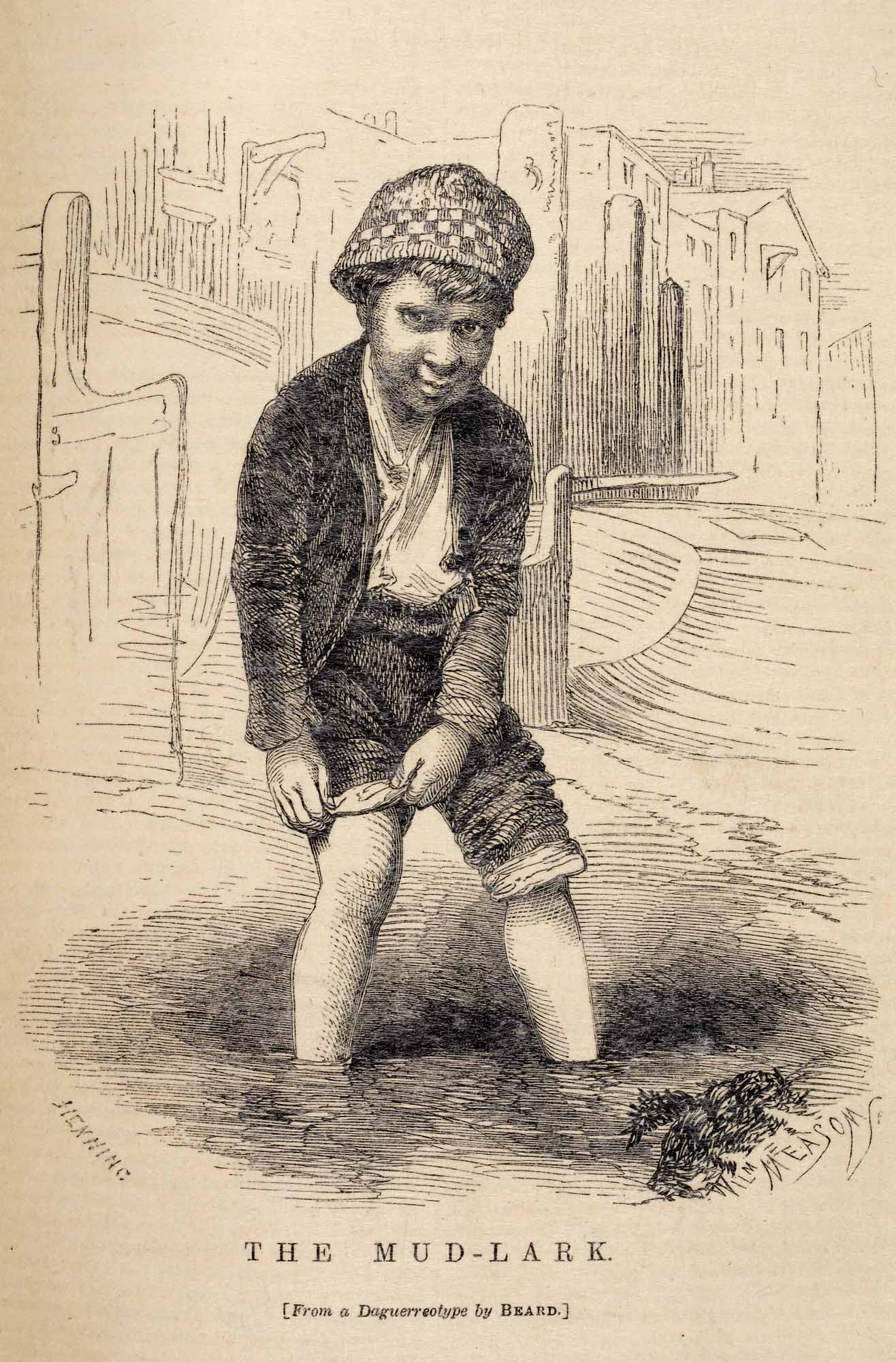

Ah, as opposed to these highly cultured English poor individuals of the time.

The mudlark – children who waded through the Thames mud to find things to sell – from Henry Mayhew’s London Labour London and London Poor, 1851

Here they are in all their high class glory.

Nobody loves living in dirt and enjoying unsavoury smells more than the Anglo slave race. They dream of returning to the glorious days when they were all living in dirt and working 12 hours per day 7 days per week while their Empire was building railroads in sub-Saharan Africa so that niggers would benefit from them.