◄►◄❌►▲ ▼▲▼ • BNext New CommentNext New ReplyRead More

The Ancient Ethnostate: Biopolitical Thought in Ancient Greece

Guillaume Durocher

Amazon Createspace, 2021

This is an extended version of the foreword to The Ancient Ethnostate.

Guillaume Durocher has produced an authoritative, beautifully written, and even inspirational account of the ancient Greeks. Although relying on mainstream academic sources, he adds an evolutionary perspective that is sorely lacking in contemporary academia at a time when the ancient Greek civilization, like the Western canon in toto, has been subjected to intense criticism reflecting the values of the contemporary academic left. To get a flavor of the current state of classics scholarship, consider the following from the New York Times:

Long revered as the foundation of “Western civilization,” the field [of classics] was trying to shed its self-imposed reputation as an elitist subject overwhelmingly taught and studied by white men. Recently the effort had gained a new sense of urgency: Classics had been embraced by the far right, whose members held up the ancient Greeks and Romans as the originators of so-called white culture. Marchers in Charlottesville, Va., carried flags bearing a symbol of the Roman state; online reactionaries adopted classical pseudonyms; the white-supremacist website Stormfront displayed an image of the Parthenon alongside the tagline “Every month is white history month.” …

For several years, [Dan-el Padilla] has been speaking openly about the harm caused by practitioners of classics in the two millenniums since antiquity: the classical justifications of slavery, race science, colonialism, Nazism and other 20th-century fascisms. Classics was a discipline around which the modern Western university grew, and Padilla believes that it has sown racism through the entirety of higher education. Last summer, after Princeton decided to remove Woodrow Wilson’s name from its School of Public and International Affairs, Padilla was a co-author of an open letter that pushed the university to do more. “We call upon the university to amplify its commitment to Black people,” it read, “and to become, for the first time in its history, an anti-racist institution.” Surveying the damage done by people who lay claim to the classical tradition, Padilla argues, one can only conclude that classics has been instrumental to the invention of “whiteness” and its continued domination.

In recent years, like-minded classicists have come together to dispel harmful myths about antiquity. On social media and in journal articles and blog posts, they have clarified that contrary to right-wing propaganda, the Greeks and Romans did not consider themselves “white,” and their marble sculptures, whose pale flesh has been fetishized since the 18th century, would often have been painted in antiquity. They have noted that in fifth-century-B.C. Athens, which has been celebrated as the birthplace of democracy, participation in politics was restricted to male citizens; thousands of enslaved people worked and died in silver mines south of the city, and custom dictated that upper-class women could not leave the house unless they were veiled and accompanied by a male relative. They have shown that the concept of Western civilization emerged as a euphemism for “white civilization” in the writing of men like Lothrop Stoddard, a Klansman and eugenicist. Some classicists have come around to the idea that their discipline forms part of the scaffold of white supremacy — a traumatic process one described to me as “reverse red-pilling” — but they are also starting to see an opportunity in their position. Because classics played a role in constructing whiteness, they believed, perhaps the field also had a role to play in its dismantling.[1]Rachel Poser, “He Wants to Save Classics from Whiteness. Can the Field Survive?,” New York Times (February 2, 2011). https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/02/magazine/classics...s.html ; see also Donna Zuckerberg, Not All Dead White Men: Classics and Misogyny in the Digital Age (Harvard University Press, 2018).

Durocher’s treatment is a refreshing antidote to this contemporary academic orthodoxy. Unlike so many scholars, whose main concern is to score political points useful to the anti-White left and thereby improve their standing in the profession, he has attempted to present an accurate account of these writers and the world they were trying to understand and survive in. The phrase “so-called white culture” in the above quotation from Rachel Poser’s New York Times article is indicative of this mindset. Durocher does not shy away from discussing slavery, the relatively confined role of women, or the cruelty that Greeks could exhibit even toward their fellow Greeks. But he also emphasizes the relative freedom of the Greeks, their intellectual brilliance, and the ability of the two principal city-states, Athens and Sparta, to pull together to defeat a common foe and thereby save their people and culture from utter destruction.

The contemporary academic left has abandoned any attempt to understand the Greeks on their own terms in favor of comparing Western cultures (and typically only Western cultures) to what they see as timeless moral criteria—criteria that reflect the current sacralization of diversity, equity, and inclusion. But even the most cursory reflection makes it obvious that moral ideals such as valuing diversity, equity, and inclusion are not justified because of their value in establishing a society that can survive in a hostile world. They are valued as intrinsic goods, and societies that depart from these ideals are condemned as evil. Recently there was something of a stir when a video was released by the website of Russia Today, a television station linked to the Russian government, comparing ads for military service in Russia and the United States.[2]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZEnxmzqXJN8 Ads directed at Russians show determined, physically fit young men engaged in disciplined military units and difficult, dangerous activities under adverse conditions. On the other hand, the recruitment ad for the U.S. military features a woman who, although physically fit, dwells on her pride in participating in the marriage of her two “mothers.” The contrast couldn’t be more striking. The Russian military is seeking the best way to survive in a hostile world, while the American military is virtue-signaling its commitment to the gender dogmas of the left.

Durocher emphasizes that the Greeks lived in a very cruel world, a world where “the fate of the vanquished was often supremely grim: the men could be exterminated, the women and children enslaved as so much war booty. Our generation too often forgets that our political order exists by virtue of a succession of wars — from the revolutionary wars of the Enlightenment to the World Wars of the Twentieth Century — and it cannot be otherwise.” We in the contemporary West have a life of relative ease, wealth, and security that was unknown to the ancient Greeks who were threatened not only by other Greek poleis, but by foreign powers, particularly the aggressive and much more populous Persian Empire. In such an environment, there is no room for virtue signaling. Survival in a hostile, threatening world was the only worthwhile goal:

Before anything else, a good city-state was one with the qualities necessary to survive in the face of aggressive foreign powers. This was ensured by solidarity among the citizens, each being willing to fight and die beside the other. Hence the citizen was also a soldier-citizen.

Aristocratic Individualism. Ancient Greece was an Indo-European culture, and thus prized military virtues, heroism, and the quest for honor, fame, and glory. Homer “tells of a terrible war for sexual competition, for the heart of beautiful Helen, and its inevitable tragedies. But the maudlin self-pity and effeminacy of our time are unknown to Homer: if tragedy is inevitable in the human experience, the poet’s role is to give meaning and beauty to the ordeal, and to inspire men to struggle for a glorious destiny.” “Their way of life is one of ‘vital barbarism,’ having the values of ruthless conquerors, prizing loot, honor, and glory above all.” Achilles “prefers a brief but glorious life to one of lengthy obscurity.” “Quick, better to live or die, once and for all, than die by inches, slowly crushed to death – helpless against the hulls in the bloody press, by far inferior men!” (Iliad, 15.510). Trust was confined to people within one’s social circle. Strangers and foreigners could not be trusted: “As in the Iliad, in the Odyssey strangers and foreign lands are synonymous with uncertainty and violence. This is a world without mutual confidence. Even the gods do not trust in one another.”

This sense of heroic struggle in a hostile environment is central to the classical world of Greece and Rome, and was evident among the Germanic peoples who inherited the West after the fall of the Roman Empire. As Ricardo Duchesne notes, the Indo-European legacy is key to understanding the restless, aggressive, questing, innovative, “Faustian” soul of Europe. Indo-Europeans were a “uniquely aristocratic people dominated by emerging chieftains for whom fighting to gain prestige was the all-pervading ethos. This culture [is] interpreted as ‘the Western state of nature’ and as the primordial source of Western restlessness.”[3]Ricardo Duchesne, The Uniqueness of Western Civilization (Leiden: Brill, 2011), p. 51. Durocher expands on this beautifully:

This Aryan ethos is what so appealed to Nietzsche: a people not animated by pity or guilt, nor trying to achieve impossible or fictitious equality in an endlessly vain attempt to assuage feelings. Rather, Hellenic culture, driven by that aristocratic and competitive spirit, held up the ideal of being the best: the best athlete, the best warrior, the best poet, the best philosopher, or the most beautiful. This culture also held up the collective ideal of being the best as a whole society, for they understood that man as a species only flourishes as a community.

This competitive ethic so central to the West is fundamentally individualistic, not based on extended kinship. It is in strong contrast to the contemporary West where the main goal of far too many of its traditional peoples is to uphold moral principles and to feel guilt for differences in wealth and accomplishment. In individualist Western culture, reputation is paramount, and in the modern West, reputation revolves mainly around being an honest, morally upstanding, trustworthy person, with moral rectitude defined by media and academic elites hostile to the Western tradition. In my Individualism and the Western Liberal Tradition I ascribe this fundamental shift in Western culture to the rise of the values of an egalitarian individualist ethic that originated among the northwestern European hunter-gatherers—an ethic that is in many ways the diametrical opposite of the Indo-European aristocratic tradition.[4]Kevin MacDonald, Individualism and the Western Liberal Tradition: Evolutionary Origins, History, and Prospects for the Future (Seattle: CreateSpace, 2019). This new ethic began its rise to predominance with the English Civil War of the seventeenth century and remains most prominent in northwest Europe, particularly Scandinavian cultures.

The aristocratic individualism of the ancient Western world implies a hierarchy in which aristocrats have power over underlings (although there was the expectation of reciprocity), but there is egalitarianism among peers. “The kings … are not tyrants: they are expected to welcome legitimate criticism from their peers and even tolerate a good deal of backtalk.” In the Iliad, the Achaean army is made of several kings and is therefore fractious, with no one having absolute power over the rest. Decisions therefore require consensus and consultation. Aristocratic individualism is always threatened by what one might term a degenerate aristocracy—the ancient tyrants and early modern European monarchs kings who aspired to complete control. For example, King Louis XIV of France (reigned 1643-1715) had power over the nobility undreamed of in the Middle Ages while his legacy of absolute rule led ultimately to the French Revolution.

Herodotus notes that a common strategy for ruling elites was to form a distinct and solidary extended family by only marrying among themselves, for example by the ruling Bacchiadae clan of Corinth (Herodotus, 5.92). This also occurred in the European Middle Ages and later as elites severed ties with their wider kinship groups and married among themselves—likely a tendency for any aristocratic society.

But even apart from peers, there was an ideal of reciprocity within the hierarchy—a fundamental feature of Indo-European culture. As I noted in Individualism and the Western Liberal Tradition:

Oath-bound contracts of reciprocal relationships were characteristic of [Proto-Indo-Europeans] and [Indo-Europeans] and this practice continued with the various I-E groups that invaded Europe. These contracts formed the basis of patron-client relationships based on reputation—leaders could expect loyal service from their followers, and followers could expect equitable rewards for their service to the leader. This is critical because these relationships are based on talent and accomplishment, not ethnicity (i.e., rewarding people on the basis of closeness of kinship) or despotic subservience (where followers are essentially unfree). (p. 34)

Such reciprocity is apparent in Homer’s world: “The Homeric ideal of kingship is one of familial solidarity, moderation, trust, piety, strength, and reciprocal duties between king and people, to the benefit of one another. Hierarchy and community are fundamentally necessary in Homer’s world. Followers require leadership and, indeed, servitude in a sense makes them foolish.”

Greek Collectivism: The Necessity of Social Cohesion

Given the exigencies of survival in a hostile world, Greek conceptions of the ideal society were firmly based on realistic assessments of what was necessary to survive and flourish. In my book Individualism and the Western Liberal Tradition,[5]Ibid.

(Kevin MacDonald, Individualism and the Western Liberal Tradition: Evolutionary Origins, History, and Prospects for the Future (Seattle: CreateSpace, 2019).) I noted that the Puritan-descended intellectuals of the nineteenth century, like today’s academic and media left, were moral idealists, constructing ideal societies on the basis of universalist moral principles, such as abolitionist ideology based on the evil of enslaving Africans. The Greeks also had ideas on the ideal society, but they were not based on moral abstractions independent of survival value. And among those values, social cohesion was paramount. Because of its inherent individualism and the practical necessity of social cohesion, Western culture has always been a balance between its individualism and some form of social glue that binds people together to achieve common interests, including forms of social control that impinge on the self-interest of at least some individuals, but also providing citizens with a stake in the system.

There is thus a major contrast between the Greeks and a slave-type society such as the Persian Empire—a contrast the Greeks were well aware of. For example, Aristotle wrote “these barbarian peoples are more servile in character than Greeks (as the peoples of Asia are more servile than those of Europe); and they therefore tolerate despotic rule without any complaint” (Politics, 1285a16). The social cohesion of the West has typically resulted from all citizens having a stake in the system. In the world of Homer, kings understood that they would benefit if the citizens are willing to fight and die for their homeland: “The Odyssey reaffirms the Iliad’s tragic message: that good order and the community can only be guaranteed by the willingness to fight and die for family and fatherland.” And Herodotus noted that Athens became a superior military power after getting rid of tyrants and developing a citizenry with a stake in the system: “while they were under an oppressive regime they fought below their best because they were working for a master, whereas as free men each individual wanted to achieve something for himself” (Herodotus, 5.78).

My interest in understanding the West has always revolved around kinship, marriage, and the family as bedrock institutions amenable to an evolutionary analysis. An important aspect of social cohesion in the West has been institutions that result in relative sexual egalitarianism among males, in contrast to the common practice (e.g., in classical China, and the Middle East, including Greece’s main foreign enemy, the Persian Empire) where wealthy, powerful males maintained large harems, while many men were unable to procreate. In ancient Greece, the importance of social cohesion can be seen in Solon’s laws on marriage (early sixth century BC). Solon’s laws had a strongly egalitarian thrust, and indeed, the purpose of his laws was to “resolve problems of deep-seated social unrest involving the aristocratic monopoly on political power and landholding practices under which the ‘many were becoming enslaved to the few.’”[6]Susan Lape, “Solon and the institution of ‘democratic’ family form. Classical Journal 98.2 (2002–2003), pp. 117-139, p. 117. As Durocher notes, Solon “abolished existing private and public debts and banned usurious loans for which the penalty for defaulting was enslavement. In his poems, Solon condemns the nation-shattering effects of usury and poverty, which lead unfree citizens to wander the world, homeless.”

The concern therefore was that such practices were leading to a lack of social cohesion—with people not believing they had a stake in the system. As in the case of the medieval Church, the focus of Solon’s laws on marriage was to rein in the power of the aristocracy by limiting the benefits to be gained by extra-marital sexual relationships. In Solon’s laws, legitimate children with the possibility of inheritance were the product of two Athenian citizens, a policy approved by popular vote in 451 B.C. As Pericles noted, bastards were to be “excluded from both the responsibilities and privileges of membership in the public household” (in Patterson, 2001, 1378). Given that wealthy males are in the best position to father extramarital children and provide for multiple sexual partners, it’s critical that Solon’s legislation (like the Church’s policies in the Middle Ages) was explicitly aimed at creating sexual egalitarianism among men—giving all male citizens a stake in the system.

Greek thinkers and lawgivers thus had no compunctions about reining in individual self-interest in the interest of the common good. For example, “Aristotle’s discussion of population policy and eugenics reflects the view which the Greeks took for granted: that the biological reproduction and quality of the citizenry was a fundamental matter of public interest. The citizen had a duty to act and the lawmaker to regulate by whatever means necessary to achieve these goals.” The public interest in achieving a society able to withstand the hostile forces arrayed against it was paramount, not the interests of any particular person or segment of the society, including the wealthy.

Greek cultures therefore often had strong social controls aimed at creating cohesive, powerful groups where cohesion was maintained by regulating individual behavior, effectively making them group evolutionary strategies. These cultures certainly did not eradicate individual self-interest, but they regulated and channeled it in such a manner that the group as a whole benefited. For example, in constructing an ideal society, Aristotle rejected a mindless libertarianism in favor of a system that had concern for the good of the society as a whole. Anything that interfered with social cohesion or any other feature that contributed to an adaptive culture had to be dealt with—by whatever means necessary.

Solon’s laws on marriage and inheritance would therefore have been analyzed by Aristotle for their effect on social cohesion. Egalitarianism, like everything else, had to be subjected to the criterion of what was best for the community as a whole, and that meant that societies should be ethnically homogeneous and led by the best people. Aristotle’s arguments for moderate democracy are not founded on abstract “rights” or a moral vision, ideas that have dominated Western thinking since the Enlightenment, “but rather, are based on what benefits the community as a whole. … Aristotle’s citizens rule and are ruled in turn, this reciprocity fostering a spirit of friendship between social classes.” “Aristotle is clear … that private property is not a right enabling individuals to be as capricious and selfish as they please, but merely a sensible way of producing wealth, whose aim must ultimately be the well-being of the community.” The social cohesion needed in a hostile world was a fundamental value that trumped any concern for individual rights. Durocher:

Aristotle’s unabashed ethics are typically Hellenic: there is no egalitarian consolation for the ugly and the misbegotten, there is no pretense that all human beings can be happy and actualized. Rather, Aristotle, like the Greeks in general, celebrates excellence. … This vision is in fact unabashedly communitarian and aristocratic: Firstly, the human species cannot flourish and fulfill its natural role unless it survives and reproduces itself in the right conditions; secondly, the society must be organized so as to grant the intellectually-gifted and culturally-educated minority the leisure to exercise their reason.

Sparta was even more egalitarian among the Spartiates, giving the citizens a stake in the system, but with an ethic that rejected effeminacy and weakness and in which individuals strived to achieve excellence in military skills. Also likely promoting social cohesion was that the Helot slave class was an outgroup that Spartans understood needed to be rigorously controlled, setting up a very robust ingroup-outgroup psychology that promoted social cohesion and high positive regard for the ingroup along with disparagement and even abuse of the outgroup. Spartan social cohesion is legendary and likely contributed to the intense solidarity needed to defeat the far more numerous Persian Empire:

By their triumph in the Persian Wars, the Greeks preserved their sovereignty and identity, setting the stage for the Golden Age of Athenian power and philosophy. The Greeks triumphed because of the winning combination of their culture of civic freedom and solidarity, and the successful alliance between Athens and Sparta, which required both cities to adopt a conciliatory attitude. Herodotus’s Histories are a poignant commemoration of the fragility and value of Greek unity.

The results have resounded down the ages:

In the Persian Wars, the Greeks showed that a small and scattered nation could, with luck, skill, and determination, triumph even over the greatest empire of the day. This example can still inspire us today and discredit all defeatism. In their victory, the Greeks were able to pass down an enormous political, cultural, and scientific heritage to generations ever since. No wonder John Stuart Mill could claim: “The Battle of Marathon, even as an event in British history, is more important than the Battle of Hastings.”

This emphasis on giving individuals a stake in the system as a mechanism for social cohesion thus has strong roots in Western culture. The political system of the Roman Republic was far from democratic, but it was also far from a narrow oligarchy, and the representation and power of the lower classes gradually increased throughout the Republic (e.g., with the office of tribune of the plebs). The highest offices, consuls and praetors with military and judicial functions, were elected by the comitia centuriata, a convocation of the military, divided into centuries, where people with property had the majority of the vote (people were assigned to a century depending on five classes of property ownership, with the lower classes voting after the wealthy; the election was typically decided before the poorer centuries could vote).

A deep concern with social cohesion enabled by having a stake in the system was also apparent in the Germanic world after the fall of the Roman Empire. Although unquestionably hierarchical, early medieval European societies had a strong sense that cultures ought to build a sense of social cohesion on the basis of reciprocity, so that, with the exception of slaves, even humble members near the bottom of the social hierarchy had a stake in the system. The ideal (and the considerable reality) is what Spanish historian Américo Castro labeled “hierarchic harmony.”[7]Américo Castro, The Structure of Spanish History, trans. Edmund L. King (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1954), p. 497; see also Américo Castro, The Spaniards: An Introduction to Their History, trans. Willard F. King and Selma Margaretten (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971).

For example, the Visigothic Code promulgated by seventh-century King Chindasuinth of Spain illustrates the desire for a non-despotic government and for social cohesion that results from taking account of the interests of everyone (except slaves). Regarding despotism:

It should be required that [the king] make diligent inquiry as to the soundness of his opinions. Then, it should be evident that he has acted not for private gain but for the benefit of the people; so that it may conclusively appear that the law has not been made for any private or personal advantage, but for the protection and profit of the whole body of citizens. (Title I, II)[8]The Visigothic Code (Forum judicum), trans. S. P. Scott (Boston, MA: Boston Book Company, 1910; online version: The Library of Iberian Resources Online, unpaginated).

http://libro.uca.edu/vcode/visigoths.htm

Thus the concern with social cohesion is a strong current in Western history.

Ethnic Diversity and Lack of Social Cohesion.

Aristotle was well aware that extreme individualism may benefit some individuals who gain when a culture discourages common identities. I recall being puzzled when doing research on the Frankfurt School that intellectuals who had been steeped in classical Marxism had developed an ideology that prized individualism—jettisoning ethnic and religious identities in favor of self-actualization and acceptance of differences.

In the end the ideology of the Frankfurt School may be described as a form of radical individualism that nevertheless despised capitalism—an individualism in which all forms of gentile collectivism are condemned as an indication of social or individual pathology. … The prescription for gentile society is radical individualism and the acceptance of pluralism. People have an inherent right to be different from others and to be accepted by others as different. Indeed, to become differentiated from others is to achieve the highest level of humanity. The result is that “no party and no movement, neither the Old Left nor the New, indeed no collectivity of any sort was on the side of truth. . . . [T]he residue of the forces of true change was located in the critical individual alone.”[9]Kevin MacDonald, The Culture of Critique: An Evolutionary Analysis of Jewish Involvement in Twentieth-Century Intellectual and Political movements (Bloomington, IN: Authorhouse, 2002; originally published: Westport, CT: Praeger, 1998), p. 165, quoting J. B. Maier, “Contribution to a critique of Critical Theory,” in Foundations of the Frankfurt School of Social Research, ed. J. Marcus & Z. Tar (New Brunswick, NJ: 1984, Transaction Books).

Aristotle understood this logic, noting that both extreme democrats and tyrants encouraged the mixing of peoples and losing old identities and loyalties. Aristotle:

Other measures which are also useful in constructing this last and most extreme type of democracy are measures like those introduced by Cleisthenes at Athens, when he sought to advance the cause of democracy, or those which were taken by the founders of [the] popular government at Cyrene. A number of new tribes and clans should be instituted by the side of the old; private cults should be reduced in number and conducted at common centers; and every contrivance should be employed to make all the citizens mix, as much as they possibly can, and to break down their old loyalties. All the measures adopted by tyrants may equally be regarded as congenial to democracy. We may cite as examples the license allowed to slaves (which, up to a point, may be advantageous as well as congenial), the license permitted to women and children, and the policy of conniving at the practice of “living as you like.” There is much to assist a constitution of this sort, for most people find more pleasure in living without discipline than they find in a life of temperance. (Politics, 1319b19)

The ancient Greeks were also aware that ethnic diversity leads to conflict and lack of common identity. As Aristotle noted, “Heterogeneity of stocks may lead to faction – at any rate until they have had time to assimilate. A city cannot be constituted from any chance collection of people, or in any chance period of time. Most of the cities which have admitted settlers, either at the time of their foundation or later, have been troubled by faction.” Realizing this, tyrants often took advantage of this evolutionary reality by importing people in order to undermine the solidarity of the people they ruled over.

It’s interesting in this regard that such efforts to undermine the homogeneity of populations continue in the contemporary West. In the wake of World War II, the activist Jewish community, in part inspired by the writings of the Frankfurt School,[10]Ibid., Ch. 5.

(Kevin MacDonald, The Culture of Critique: An Evolutionary Analysis of Jewish Involvement in Twentieth-Century Intellectual and Political movements (Bloomington, IN: Authorhouse, 2002; originally published: Westport, CT: Praeger, 1998), p. 165, quoting J. B. Maier, “Contribution to a critique of Critical Theory,” in Foundations of the Frankfurt School of Social Research, ed. J. Marcus & Z. Tar (New Brunswick, NJ: 1984, Transaction Books).) made a major push to open up immigration of Western countries to all the peoples of the world, their motive being a fear of ethnically homogeneous White populations of the type that had turned against Jews in Germany after 1933.[11]Ibid., Ch. 7.

(Kevin MacDonald, The Culture of Critique: An Evolutionary Analysis of Jewish Involvement in Twentieth-Century Intellectual and Political movements (Bloomington, IN: Authorhouse, 2002; originally published: Westport, CT: Praeger, 1998), p. 165, quoting J. B. Maier, “Contribution to a critique of Critical Theory,” in Foundations of the Frankfurt School of Social Research, ed. J. Marcus & Z. Tar (New Brunswick, NJ: 1984, Transaction Books).) Corroborating this assessment, historian Otis Graham notes that the Jewish lobby on immigration “was aimed not just at open doors for Jews, but also for a diversification of the immigration stream sufficient to eliminate the majority status of western European so that a fascist regime in America would be more unlikely.”[12]Otis Graham (2004). Unguarded Gates: A History of American’s Immigration Crisis. (Rowman & Littlefield), p. 80. The motivating role of fear and insecurity on the part of the activist Jewish community thus differed from other groups and individuals promoting an end to the national origins provisions of the 1924 and 1952 laws which dramatically lowered immigration and restricted immigration to people largely from northwestern Europe. These same intellectuals and activists have also pathologized any sense of White identity or sense of White interests to the point that it’s common for White liberals to have negative attitudes about White people.

Greek Race Realism. The ancient Greeks were vitally concerned with leaving descendants and they understood that heredity was important in shaping individuals—a view that is obviously adaptive in an evolutionary sense. Aristotle writes that “good birth, for a people and a state, is to be indigenous or ancient and to have distinguished founders with many descendants distinguished in matters that excite envy” (Rhetoric, 1.5). The Greeks also had a sense that they shared a common ethnicity and culture with other Greeks, resulting in common expressions of the need for ethnic solidarity, particularly in the wars with Persia. Durocher notes that “One cannot exaggerate the pervasiveness of the rhetoric of kinship and pan-Hellenic identity throughout the conflict.”

The Greeks were thus proud of their lineage and had a sense of common kinship. However, it was not the sort of extensive kinship that is typical of so much of the rest of the world. There was an individualist core to Greek culture stemming from its Indo-European roots, resulting in the famously fractious Greek culture, with wars between Greek city-states. Even during the Persian wars, several Greek city-states failed to join the coalition against Persia, and “the sentimental love for Hellas was often overridden by personal or political interests. Prominent Greek leaders and cities frequently collaborated with the Persians, either because the alternative was oblivion or simply for profit.”

As in individualist cultures generally, lineage is confined to close relatives, and there are no corporate kinship-based groups that own property or where brothers live together in common households: “Despite typically vague modern notions of a primitive clan-based society as the predecessor to the historical society of the polis, early Greek society seems securely rooted in individual households—and in the relationships focused on and extending from those households.[13]C.B. Patterson, The Family in Greek History (Cambridge, MA: 2001, Harvard University Press), pp. 46–47.

And congruent with contemporary behavior genetic research, there was an expectation that children would inherit the traits of parents: King Menelaus is impressed by Odysseus’s son Telemachus: “Surely you two have not shamed your parentage; you belong to the race of heaven-protected and sceptered kings; no lesser parents could have such sons” (4.35-122). Menelaus later adds: “What you say, dear child, is proof of the good stock you come from” (4.549-643).

Reflecting the common Greek view that it was necessary to regulate society in order to achieve adaptive goals of the city as a whole, the Greeks accepted the idea that individual behavior needed to be regulated in the common interest, resulting in eugenic proposals by philosophers and, in the case of Sparta at least, practices such as killing weak infants. Both Plato and Aristotle accepted eugenics as an aspect of public policy. Plato was particularly enthusiastic about eugenics—Durocher labels it “an obsession,” and, like many evolutionists, such as Sir Francis Galton, he was much impressed by animal breeding as a paradigm for eugenic policies for humans. For Plato, eugenics was part of a broader group evolutionary strategy he proposed for the Greeks. As Durocher notes, Plato advocated

a great reform of convention grounded in reason and expertise, to transform Greece into a patchwork of enlightened, non-grasping city-states, cultivating themselves intellectually and culturally, reproducing themselves in perpetuity through systematic and eugenic population policies, avoiding fratricidal war and imperialism among themselves, and working together against the barbarians, under the leadership of the best city-states. Taken together, I dare say we can speak of a Platonic Group Evolutionary Strategy for Greece.

It’s worth noting in this context that the basic premises of eugenics are well-grounded in evolutionary and genetic science and were broadly accepted in Western culture, even among progressives, from the late nineteenth century until after World War II when the entire field became tarred by association with National Socialism. It is thus part of the broad transformation among Western intellectuals away from thinking in terms of racial differences and the genetic basis of individual differences—to the point that it’s currently fashionable to deny the reality of race and any suggestion that race differences in socially important traits such as intelligence could possibly be influenced genetically. As Durocher notes, “Race is, especially in geographically contiguous land masses, typically a clinal phenomenon, with gradual change in genetic characteristics (i.e., allele frequencies) as one moves, for instance, from northern Europe to central Africa.” However, in the contemporary West, intellectual and cultural elites have sought “to suppress cultural chauvinism and ethnic solidarity, for example by glorifying foreign cultures and shaming native ethnic pride. Such nations are unlikely to survive long however.” So true.

Scientific Think as Characteristic of the West

In his discussion of Herodotus, Durocher describes the “beginnings of scientific thought concerning both nature and society, for instance with plausible speculations about the formation of the Nile Delta, micro-climates, and the effect of the natural environment on human biology and culture.” Analogical thinking is fundamental to science (e.g., Christiaan Huygens’s use of light and sound to support his wave theory of light; Darwin’s analogy between artificial selection and natural selection—with obvious implications for eugenics; the mind as a blank slate or computer). Scientific thinking is thus apparent in the eugenic recommendations noted by Greek philosophers based, as they were, on analogies with animal breeding.

Such scientific thinking is a unique characteristic of Western individualist culture. In his book The WEIRDest People in the World, Joseph Henrich describes “WEIRD psychology”—i.e., the psychology of Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic people. A major point is that the psychology of Western peoples is unique in the context of the rest of the world: “highly individualistic, self-obsessed, control-oriented, nonconformist, and analytical. … When reasoning WEIRD people tend to look for universal categories and rules with which to organize the world.” (21)

Henrich notes that people from cultures with intensive kinship are more prone to holistic thinking that takes into account contexts and relationships, whereas Westerners are more prone to analytic thinking in which background information and context are ignored, leading ultimately to universal laws of nature and formal logic. I agree with this,[14]MacDonald, Individualism and the Western Liberal Tradition, 112–113. but, while Henrich argues that analytical thinking began as a result of the policies on marriage enforced by the medieval Church, this style of thinking can clearly be found among the ancient Greeks. Consider Aristotle’s logic, a masterpiece of field independence and ignoring context, in which logical relationships can be deduced from the purely formal properties of sentences (e.g., All x’s are y; this is an x; therefore, this is a y); indeed, in Prior Analytics Aristotle used the first three letters of the Greek alphabet as placeholders instead of concrete examples. Or consider Euclidean geometry, in which theorems could be deduced from a small set of self-evident axioms and in which the axioms themselves were based on decontextualized figures, such as perfect circles and triangles, and infinite straight lines. Despite its decontextualized nature, the Euclidean system has had huge applications in the real world and dominated thinking in geometry in the West until the twentieth century.

Ancient Greece was an Indo-European-derived culture (Individualism, Ch. 2) and, beginning in the Greco-Roman world of antiquity, logical argument and competitive disputation have been far more characteristic of Western cultures than any other culture area. As Duchesne notes, “the ultimate basis of Greek civic and cultural life was the aristocratic ethos of individualism and competitive conflict which pervaded [Indo-European] culture. … There were no Possessors of the Way in aristocratic Greece; no Chinese Sages decorously deferential to their superiors and expecting appropriate deference from their inferiors. The search for the truth was a free-for-all with each philosopher competing for intellectual prestige in a polemical tone that sought to discredit the theories of others while promoting one’s own.”[15]Duchesne, The Uniqueness of Western Civilization, 452,

In such a context, rational, decontextualized arguments that appeal to disinterested observers and are subject to refutation win out. They do not depend on group discipline or group interests for their effectiveness because in Western cultures, the groups are permeable and defections based on individual beliefs are far more the norm than in other cultures. As Duchesne notes, although the Chinese made many practical discoveries, they never developed the idea of a rational, orderly universe guided by universal laws comprehensible to humans. Nor did they ever develop a “deductive method of rigorous demonstration according to which a conclusion, a theorem, was proven by reasoning from a series of self-evident axioms,”[16]Ibid.

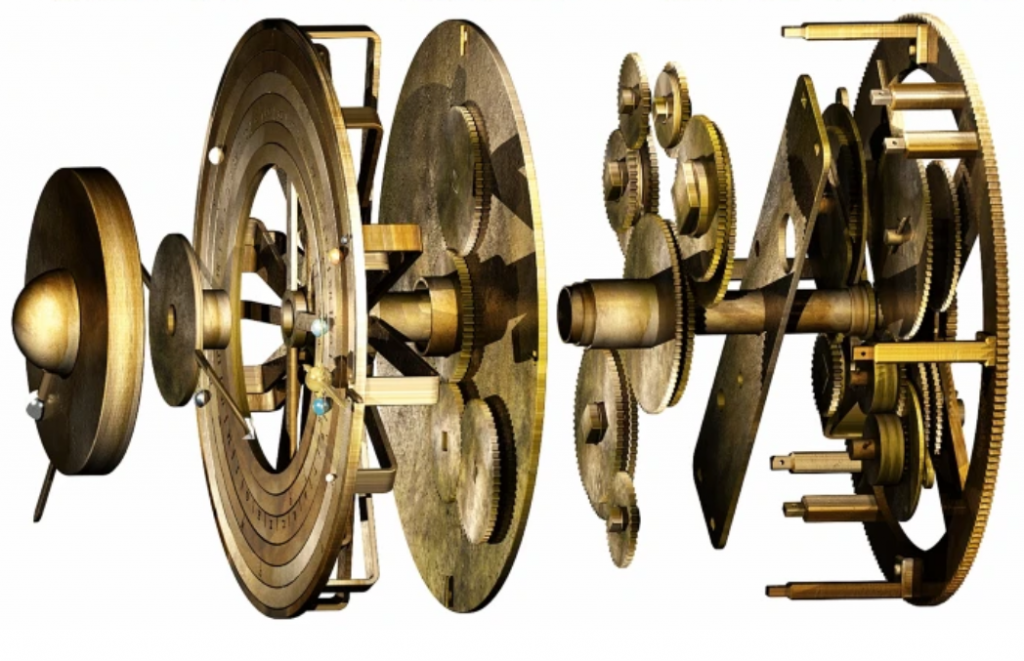

(Duchesne, The Uniqueness of Western Civilization, 452,) as seen in Aristotle’s Prior Analytics. Indeed, I can’t resist noting the intelligence and creativity that went into creating the incredibly intricate Antikythera Mechanism designed by an unknown Greek (or Greeks). Dated to around 150–100 B.C. and “technically more complex than any known device for at least a millennium afterwards,” it was able to predict eclipses and planetary motions decades in advance.[17]S. Freeth, et al. (2006). Decoding the ancient Greek astronomical calculator known as the Antikythera Mechanism . Nature 444: 587-591, 587. Western scientific and technological creativity did not begin after the influence of Christianity, the Renaissance, or the Industrial Revolution.

As Durocher notes, “The fruits of Hellenic civilization are all around us, down to our very vocabulary.”

Conclusion

The Ancient Ethnostate should be at the top of everyone’s reading for those interested in understanding Western origins and the uniqueness of the West. It is also an inspiring work for those of us who seek to reinvigorate the West as a unique biocultural entity. The contemporary West, burdened by loss of confidence and moral and spiritual decay, cannot be redeemed by a fresh influx of ethnically Western barbarians as happened with the collapse of the Roman Empire and the rise of Germanic Europe. There are no more such peoples waiting in the wings to revive our ancient civilization.

Reinvigoration must come from within, but now it must do so in the context of massive immigration of non-Western peoples who are addicted to identity politics and are proving to be unwilling and likely unable to continue the Western traditions of individualism and all that that implies in terms of representative, non-despotic government, freedom of speech and association, and scientific inquiry. Indeed, we are seeing increasing hatred toward the people and culture of the West that is now well entrenched among Western elites and eagerly accepted by many of the non-Western peoples who have been imported into Western nations, many with historical grudges against the West. It will be a long, arduous road back. The Ancient Ethnostate contains roadmaps for the type of society that we should seek to establish.

Notes

[1] Rachel Poser, “He Wants to Save Classics from Whiteness. Can the Field Survive?,” New York Times (February 2, 2011). https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/02/magazine/classics-greece-rome-whiteness.html ; see also Donna Zuckerberg, Not All Dead White Men: Classics and Misogyny in the Digital Age (Harvard University Press, 2018).

[2] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZEnxmzqXJN8

[3] Ricardo Duchesne, The Uniqueness of Western Civilization (Leiden: Brill, 2011), p. 51.

[4] Kevin MacDonald, Individualism and the Western Liberal Tradition: Evolutionary Origins, History, and Prospects for the Future (Seattle: CreateSpace, 2019).

[5] Ibid.

[6] Susan Lape, “Solon and the institution of ‘democratic’ family form. Classical Journal 98.2 (2002–2003), pp. 117-139, p. 117.

[7] Américo Castro, The Structure of Spanish History, trans. Edmund L. King (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1954), p. 497; see also Américo Castro, The Spaniards: An Introduction to Their History, trans. Willard F. King and Selma Margaretten (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971).

[8] The Visigothic Code (Forum judicum), trans. S. P. Scott (Boston, MA: Boston Book Company, 1910; online version: The Library of Iberian Resources Online, unpaginated).

http://libro.uca.edu/vcode/visigoths.htm

[9] Kevin MacDonald, The Culture of Critique: An Evolutionary Analysis of Jewish Involvement in Twentieth-Century Intellectual and Political movements (Bloomington, IN: Authorhouse, 2002; originally published: Westport, CT: Praeger, 1998), p. 165, quoting J. B. Maier, “Contribution to a critique of Critical Theory,” in Foundations of the Frankfurt School of Social Research, ed. J. Marcus & Z. Tar (New Brunswick, NJ: 1984, Transaction Books).

[10] Ibid., Ch. 5.

[11] Ibid., Ch. 7.

[12] Otis Graham (2004). Unguarded Gates: A History of American’s Immigration Crisis. (Rowman & Littlefield), p. 80.

[13] C.B. Patterson, The Family in Greek History (Cambridge, MA: 2001, Harvard University Press), pp. 46–47.

[14] MacDonald, Individualism and the Western Liberal Tradition, 112–113.

[15] Duchesne, The Uniqueness of Western Civilization, 452,

[16] Ibid.

[17] S. Freeth, et al. (2006). Decoding the ancient Greek astronomical calculator known as the Antikythera Mechanism . Nature 444: 587-591, 587.

RSS

RSS