◄►◄❌►▲ ▼▲▼ • BNext New CommentNext New ReplyRead More

Mea culpa

Before detailing my primary critique of Jonathan Haidt’s book, “The Righteous Mind”, I would like to offer a mea culpa. This essay was intended to be a refutation of the book’s main finding, but in conceiving how best to convey my disagreement I have found it more necessary to qualify Haidt’s thesis rather than outright deny it. In the near decade that has passed since first reading Dr. Haidt’s book, my feeling that his ‘3v6’ model of political morality was flawed never waned, I simply struggled to articulate why I thought it was wrong. I had to change how I thought about his argument (and further my own political education) before I could begin to work out my own counterargument.

It is not on psychological – nor even, strictly speaking, scientific – grounds upon which I feel Dr. Haidt’s theory fails, but rather the deeper commitments, unconscious or otherwise, which frame the scope and schema of his investigation. Hyperattention to the content of his theory (as opposed to its form, and perhaps, even origin) led to a theoretical stalemate from which, for a long time, I was unable to recover. Only by overcoming this initial hurdle was I finally able to reach the conclusion I will be presenting here.

Haidt offers us a story of political morality, that Liberals are less morally integrated than Conservatives, but does not attempt a further account of this finding. Therein lies the problem: we assume, because of Haidt’s formulation, that Liberals are somehow morally defective. The heavily evolutionist framing utilized throughout the work primes the reader to essentialize Haidt’s finding: Liberals are moral inferiors. What I believe amounts to pseudo-Conservative apologia, the legacy of which has essentially proven to be “Libs are Bad”, nonetheless offers valuable insight and did create a Liberal-skeptic space to discuss political psychology (without which my own theoretical writing would not be possible). Unfortunately for Dr. Haidt, his story just doesn’t hold up.

With regards to political psychology, it is the former which I will be addressing throughout my critique, and not the latter. I will also be challenging the philosophical, or shall we say paradigmatic, grounding from which Dr. Haidt’s inquiry stems. The Conservative intuition (“Something is wrong with Liberals”), validated by Haidt’s Moral Foundations Theory, correctly identifies a social problem which sadly has been obfuscated by Haidt’s ideological framing (ideological in the sense of obscuring power relations). For readers unfamiliar with Haidt’s work, I will provide as thorough (and hopefully brief) a primer as I can before moving swiftly into my counterargument. While I am similarly committed to Dr. Haidt’s goal, that being the improvement of America’s political fortunes, I do not share his desire to fortify partisan Democrat political strategy.

Dr. Haidt’s work sought to elevate Liberal political rhetoric while validating Conservative political sensibilities, a worthwhile goal perhaps but not one that I wish to pursue here. Nonetheless, we are all aided by elevating our understanding of the political circumstances at hand and their downstream psychological consequences (and by offering a few significant qualifications of Dr. Haidt’s theory will achieve, I hope, just that).

A righteous find

The driving insight which motivated Jonathan Haidt to publish “The Righteous Mind”, its central conclusion, and the raison d’etre for Dr. Haidt’s political activity is the notion that Left-Liberals (Progressives) are less morally robust than Right-Liberals (Conservatives). As for what exactly that means, for the moment it is enough to simply say that psychologically speaking, Progressive moral reasoning operates on fewer “axioms” (in Haidt’s terms, “foundations”) as do those of Conservatives.

Challenging this idea – or, at least, significantly qualifying it – will be the goal of this essay though before we do, a few things must be said in praise of Haidt’s work. It may be that we are dealing with a case of “directionally correct, factually incorrect” more than outright falsehood for Haidt’s error surreptitiously ushered in America’s cultural Right-ward turn. This alone is a significant accomplishment, as it represents a major concession on behalf of the Liberal establishment towards those populations it had spent so much time and effort denigrating. “The Righteous Mind” was an important book for me personally, as it set me on the path of taking my psychological training in a more political and philosophical direction. No doubt, it had the same effect on countless others. Right or wrong, Haidt proved to be the canary in the coal mind for the coming Conservative intellectual revolution.

Published in March of 2012 (some eight months ahead of then President Barack Obama’s successful re-election bid), Haidt’s book gave a scientific voice to the growing dissatisfaction with Progressive Liberalism’s cultural hegemony. Dr. Haidt walked a very fine line by affirming dangerous scientific and philosophic heresies (e.g., group selection, “irrationalism”, etc.) while upholding enough doctrinal Liberal social theorizing (e.g., secular humanism, mass democracy) to get his ideas through the gate. Bemoaning Conservative underrepresentation in the Academy, Haidt followed up his publication by co-founding the Heterodox Academy, a non-profit advocacy group dedicated to restoring intellectual and political diversity on college campuses. Just a few short years later we would get Brexit, Trump, the Intellectual Dark Web, Joe Rogan as the voice of the common man (set against the dominance of Liberal culture), and the emergence of a new center right economy whose sole unifying principle was an ever-intensifying rejection of the Liberal arrogance which had obnoxiously sauntered its way into American culture beginning in 2009. Haidt didn’t start the fire, but the Moral Foundations Theory was his attempt to fight it.

“The Righteous Mind” served not only as a genuine advancement of social theory (specifically within the discipline of moral psychology), but as an autobiographical documentation of its author’s own rightward drift. Haidt began the book with an examination of his exuberant youthful Liberal priors only to note in the final chapters, his shocking discovery that it is in fact Conservatism which best provides those things he valued so dearly as a devout Liberal. Conservatism, Haidt tells us, is responsible for providing the greatest happiness for the most, while Liberalism overreaches – changing too many things too quickly – thereby inadvertently lowering the stock of “moral capital”. Moral capital, in Jonathan Haidt’s words, refers to:

“[T]he degree to which a community possesses interlocking sets of values, virtues, norms, practices, identities, institutions, and technologies that mesh well within evolved psychological mechanisms and thereby enable the community to suppress or regulate selfishness and make cooperation possible.”[1]Haidt, Jonathan. 2012. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. New York: Vintage Books. p. 341

Progressive Liberalism, for all the good it may have brought us, Haidt argued, is now tearing us apart from the inside. Haidt’s political career, which had begun all the way back in 2004 during the time of John Kerry’s abysmal presidential bid, had brought him over a decade later to the following fact: Conservatism operates, just as Liberalism does, within the paradigm of Enlightenment thinking, and that, in fact, Conservatism is the true ideological progenitor of the West’s ever self-refining moral tradition. Haidt’s wish to expand the Liberal “moral matrix”, thus helping the Democrat party better reach the American people now required him to convince his partisan fellows to start seeing Conservatives more humanely. Though it does not appear that the DNC has quite received Haidt’s good-faith message (despite the many “post-Left” movements which have arisen in recent years), his psychological research has nonetheless contributed to a growing Conservative (or Rightist) movement – a contribution which we should all feel indebted to.

The foundation of Haidt’s “Moral Foundations Theory”

Let’s take a moment to briefly summarize the main points of Jonathan Haidt’s book. Before sharing the findings of his research into our moral foundations, Dr. Haidt lays out a handful of axioms (taken from other disciplines: anthropology, philosophy, and sociology) which are intended to contextualize his research, providing a framework with which to make sense of his own original discoveries. In the introductory chapter Dr. Haidt declares that

“If you think that moral reasoning is something we do to figure out the truth, you’ll be constantly frustrated by how foolish, biased, and illogical people become when they disagree with you. But if you think about moral reasoning, as a skill we humans evolved to further our social agendas– to justify our own actions and defend the teams we belong to – then things will make a lot more sense.”[2]Haidt, Jonathan. 2012. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. New York: Vintage Books. p. 341

As we will soon see, morality is (in Haidt’s account) a feature of human life which serves multiple masters.

Dr. Haidt wants to answer the following question: is morality the byproduct of our intrinsic biological condition or does it emerge due to our cognitive efforts? He begins his answer with the following history lesson: prior to 1987, questions of moral cognition were relegated to the discipline of developmental psychology, to which most researchers interested in the subject fell into either one of two camps: nativism (moral knowledge is pre-given) and empiricism (the theory of a cognitive blank slate). But then a tidal wave of rationalism emerged to break the stalemate, demonstrating rather convincingly that moral cognition is a progressive faculty which develops in tandem with our physical maturation, resulting in a cognition that is self-constructed. Jean Piaget, the progenitor of this style of thinking, developed a series of widely reproduced empirical measures which opened an entirely new space for empirical psychology, what Haidt terms “psychological rationalism”. This initial groundwork was later completed – and in effect, consecrated – by Lawrence Kohlberg, a moral psychologist and Piaget’s most prominent ideological successor.

Dr. Kohlberg further developed Piaget’s theory by building it into a complete moral-psychological paradigm, one that happened to be fully consistent with the secular liberalism of his time. As a result of his experimentation, Kohlberg postulated a moral-cognitive system which validated Piaget’s findings but then went a step further: claiming a progressive development of the individual’s moral reasoning abilities, Dr. Kohlberg declared its culmination in what he termed “post-conventional” (‘PC’, henceforth) moral reasoning. At this stage, individuals can trade in Kantian categorical imperatives or Kierkegaardian suspensions of the ethical in pursuit of establishing their own internally consistent and individualistic moral weltanschauung.

Kohlberg, as was true of Piaget, felt that formal authority stifled the individual’s moral development, a prejudice which came to define his theory of moral reasoning. Of this Haidt says,

“[B]ut by using a framework that predefined morality as justice, while denigrating authority, hierarchy and tradition, it was inevitable that the research would support world views that were secular, questioning, and egalitarian.”[3]Ibid, p. 10

(Haidt, Jonathan. 2012. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. New York: Vintage Books. p. 341)

Elliot Turiel, Kohlberg’s protégé, further narrowed the Western scientific conception of morality thanks to his own research. According to Turiel, children recognize that rules which prevent harm (“moral rules”) are categorically different from “conventional rules” (rules about clothing, food, etc.) which are arbitrary and expendable. Important to note is that Turiel defined rules as being related to “justice, rights, and welfare pertaining to how people ought to relate to each other” (p. 11). Children seem to grasp early on that rules which prevent harm are “special, important, unalterable, and universal” (p. 12). Dr. Turiel claims this realization is the foundation of all moral development: children construct their moral understanding on the basis that harm is wrong. Specific rules may vary across cultures, but in all the cultures Turiel examined, children still made a distinction between moral rules and conventional rules.

“Turiel‘s account of moral development differed in many ways from Kohlberg’s, but the political implications were similar: morality is about treating individuals well. It’s about harm and fairness; hierarchy and authority are generally bad things.”[4]Ibid, p. 12

(Haidt, Jonathan. 2012. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. New York: Vintage Books. p. 341)

This picture of morality as portrayed by 20th-century social scientists is indeed a queer one, fixed almost entirely on abstract reasoning. Recognizing this, Haidt invoked the acronym “WEIRD” (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic) to describe our moral sensibilities (largely limited to the “ethic of autonomy”), eventually placing them in stark contrast to those outside of the West’s purview (which are broader, including the “ethics of community and divinity”). Dissatisfied with where his own psychological training had brought him, Dr. Haidt turned to other scientific disciplines for aid in excavating the origins of human morality.

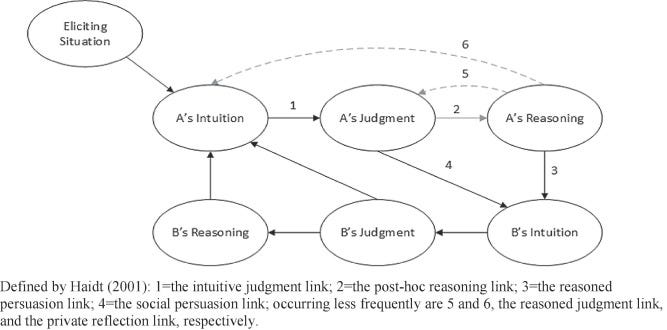

University of Chicago anthropologist Richard Shweder’s work highlighted this very dichotomy. Shweder argued that different societies all come to their own conclusions about how to order society, and how to balance the needs of the individual against those of the group. Dr. Shweder’s work showed that outside of the West, moral dilemmas are resolved by more than just appeals to fairness and harm reduction (a finding that Dr. Haidt was able to replicate as a graduate student), and that there were in fact a wide range of “moral intuitions” which guide our thoughts and judgements. Haidt’s own experimentation (intended to settle the dispute between Turiel and Shweder, that is, between WEIRD victimology and sociocentric views of morality), demonstrated that Westerners often struggled to articulate why a given scenario was morally impermissible absent a clear victimological framework, though they were clearly in the grips of a moral judgement. Findings such as these demonstrate that morality, Dr. Haidt tells us, is a post hoc justification of our immediate (and visceral) emotional experience. They also tell us that intuition is an important feature of human cognition.

Drawing from Sir Edward Evan Evans-Pritchard’s research on the Azande tribe of Sudan, Haidt came to a functionalist/evolutionary understanding of morality and religion. According to Pritchard’s work, the Azande believed that witches were just as likely to be men as they were women, thus the fear of being called a witch made the Azande careful not to anger or induce envy in their neighbors. “That was my first hint that groups create supernatural beings, not to explain the universe, but to order their societies”, Haidt says (p. 13). Renato and Michelle Rosado’s seminal work on the Ilongot tribe of the Philippines provided Dr. Haidt with another crucial insight. The young men of the Ilongot tribe gained honor by beheading their rivals. Some of these beheadings resulted from revenge killings, but many of these murders were committed against strangers who were not involved in any kind of feud with the killer. It has been suggested that these killings are intended to channel the resentments and frictions of young men within the group into the formation (and subsequent strengthening) of hunting parties. “This was my first hint that morality often involves tension within the group, linked to competition between different groups” (p. 14).

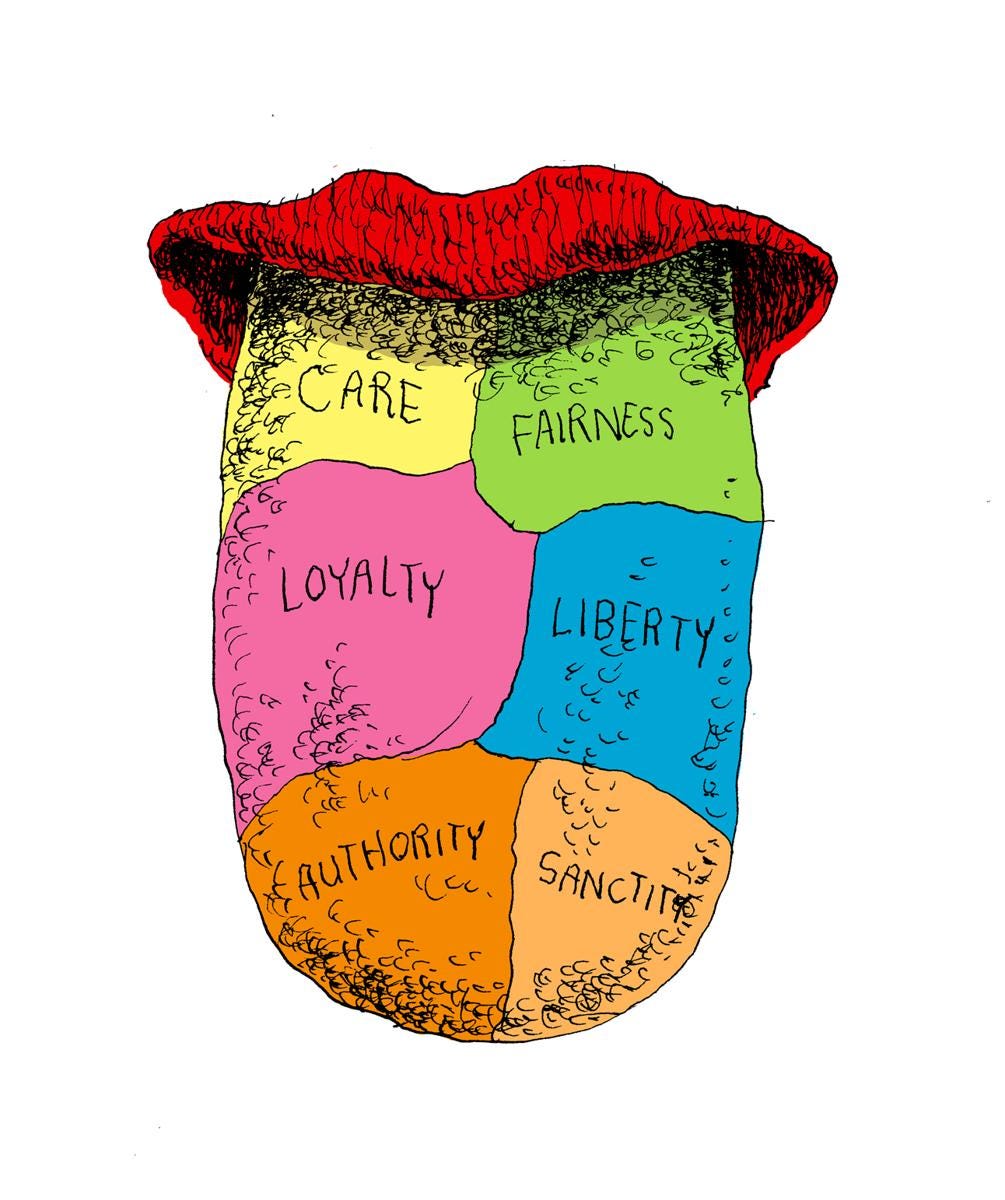

Haidt provides us with a clear picture of human nature: we are tribal, hive creatures, adapted to our surroundings by generation after generation of group selection. Following from this, he argues that our moral reasoning largely works to fortify our tribe. Important to note, however, is that our moral reasoning is often a servant of moral intuitions. As such, these moral intuitions (or emotions) are critical to human cognition and therefore, must necessarily be understood before throwing oneself into social engineering as a means for resolving man’s political woes. Perhaps, in misunderstanding our nature as moral animals, we misunderstand the nature of the problems we face, Haidt suggests. “Morality binds and blinds”, he says. Upon this foundation, Dr. Haidt erected his own theory of moral reasoning, positing 6 basic moral intuitions: care/harm, fairness/cheating, liberty/oppression, loyalty/betrayal, authority/subversion, and sanctity/degradation. Secular Western moralities – which is to say, progressive liberal morality – broadly attempts to stimulate only a few of these foundations (care/harm, fairness/cheating, liberty/oppression), a psychological and political reality which Dr. Haidt has since devoted himself to changing.

“We’re born to be righteous, but we have to learn what exactly people like us should be righteous about.”

3 to 6: Deficiency or (over)refinement?

A liberal’s moral palate, Haidt argues, largely draws upon the following three foundations: care/harm, fairness/cheating, and liberty/oppression, while that of the average conservative’s is informed by all six (including loyalty/betrayal, authority/subversion, and sanctity/degradation. These foundations, or intuitions, arose out of an originary social scene which we have since “evolved” out of – though we are still triggered by contemporary equivalents of those same challenges (now provoking us through increasingly surrogate and abstract formulations). Citing the work of neuroscientist Gary Marcus, Dr. Haidt qualifies his evolutionist framework: our intuitions are prewired and not hardwired; biology is the first draft, while our lived experience serves as the chief editor of human psychology. Over the course of a lifetime, we construct our own moral worldview.

Haidt observes a further challenge: depending on one’s political orientation, our intuitions are held with contrasting semantic values. For instance, “fairness” implies equality to liberals but proportionality to conservatives. While both sides value fairness to one degree or another, they tend to evaluate the meaning of the word differently. Said simply, not only do liberals and conservatives generally formulate their moral evaluations based on different intuitions, but in those instances where their intuitions overlap, they often intend different meanings. “Sanctity” is another such intuition wherein liberals and conservatives differ radically, though not for semantic reasons but ideological ones. Conservative applications of the “sanctity” intuition reflect their commitment to traditional institutions and norms, whereas it manifests among liberals according to their secular humanist worldview (decrying sanctity when it comes to conventional sexual mores and biomedical issues, but valuing it, for instance, when it comes to matters of environmentalism and spirituality). Not only do we evaluate moral challenges based on differing intuitions, but we also mean different things when we say we hold a certain moral intuition. Furthermore, even when we apply the same intuitions we tend to apply them differently (for instance, applying the same intuition but to entirely different – and in many cases competing – domains of life).

Allegiance to one intuition may impair allegiance(s) to others. Haidt says that the liberal’s “loyalty” foundation is impaired both by their commitments to universalism, as well as to the “care” foundation, making them less likely, to use an example Haidt himself provides, to support American foreign policy initiatives. Liberal equalitarianism, derived as we have noted from their commitment to “fairness”, compromises their ability to appeal to the “authority” intuition as they are reflexively anti-authoritarian (after all, an end to authority and hierarchy also means an end to oppression, and therefore, the emergence of a truly “fair” society). At least this is the picture as presented by Dr. Haidt. It would seem then that ideological anti-hierarchism results in moral anarchy, such that the liberal individual’s moral schema undermines its own function.

But why? How did liberal moral reasoning become so tortured? And what is it about conservatism that preserves a holistic moral palate? Furthermore, are we certain that what has been measured is, in fact, a fundamentally psychological phenomenon (more on that in a moment)? Haidt acknowledges that progressive liberalism has an intrinsically corrosive effect on the social order before begrudgingly affirming the wisdom of classical liberalism (conservatism), however his prescription does not appear strong enough. We should affirm and own our essential tribe-centered self-righteousness and learn to get along, Haidt suggests (the Gene Roddenberry recommendation, in effect). We can transcend our inner chud-simpleton (or conversely, overcome the inner soy-libtard) and soar to ever greater heights of intergalactic pluralism! But can we? Not if we operate under the same premises as Dr. Haidt.

If the events of the 2016 presidential election have taught us anything, it is that we cannot all get along. Moreover, it taught us that “we” are not a “we” at all, and that there is no grand “Us”, rather, we are truly composed of pockets of existential cohesion which find themselves inexorably in conflict with one another. So, the first problem which strikes us is the erroneous presumption of homogeneity. If liberals and conservatives are not part of this “grand Us”, then who are they and from where do they originate? The problem of “liberal deficiency” derives, as we will see, from this mistaken belief in a common unity.

To address both items simultaneously (e.g., the moral deficiency of liberals, and the presumptive psychological homogeneity of Americans), let us instead presume the following: expressions of liberal and conservative moral intuition are not mere psychological phenomenon reducible to the inherited and acquired conditions of the individual person’s existence, but instead are the result of specific modes of political organization (both of which are historically contingent in their founding and are presently in conflict with one another). Haidt repeatedly evokes Darwinian theory throughout his work, suggesting even that we might underestimate the speed at which evolution occurs, but I do not believe that the difference between liberals and conservatives at present is an essentially genetic one, but rather a political and technological one (though it should be said that this bifurcation may, in the end, become inexorably genetic if it hasn’t already).

Although Haidt made the transition from a liberal worldview to one that is more conservative, his location of the two as operating, essentially, within the Enlightenment paradigm is ultimately fatal to his analysis. Remaining as committed to his secular humanism now as in his youth, Haidt pins both the origins of political dysfunction – and their solution – inappropriately on the individual person. As I will soon demonstrate, our challenges are political-civilizational and not private-psychological. And while Haidt never explicitly states as much, his evolutionist framing when combined with his goal of helping liberals to rhetorically close the gap on what he calls “the conservative advantage” suggests that the liberal person’s moral cognitive ability is in some fundamental way, deficient.

While it is certainly not Dr. Haidt’s fault that popular perception has caught up with decades of conservative talk radio rhetoric (consider Michael Savage’s famous catchphrase: “Liberalism is a mental disorder!”), thanks to the sheer volume of studies released in the years following his book’s publication – all of which paint an unflattering picture of liberal mental health (e.g., higher rates of psychoticism and neuroticism, greater instances of depression, greater likelihood to seek psychotherapeutic and pharmacological interventions, et cetera) – the received wisdom of this book has been: libs bad. The imploding credibility of formerly well-regarded “liberal” institutions has also contributed greatly to the notion of a dysfunctional liberalism. Ultimately, Haidt’s image of the “morally deficient liberal” was simply one more brick in the conservative rhetorical wall. Regardless of how this misconception first arose, it requires correcting. It follows from the argument which I will now present that this peculiarity of liberal moral cognition is not a failure of individual character or even partisan political strategery, but the logical outcome of a system of political organization staked on differing foundational axioms than the one which preceded it.

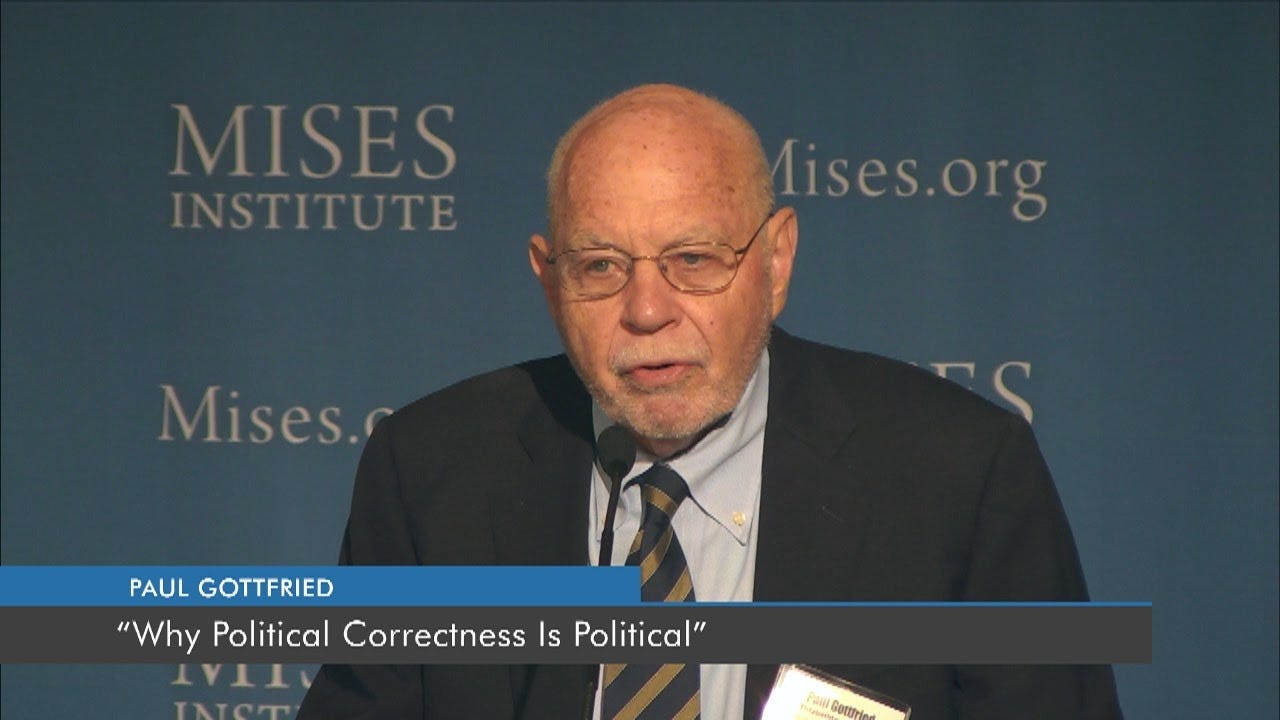

The core confusion which muddles Dr. Haidt’s finding may be attributed to what Paul Gottfried has termed “the semantic problem of liberalism” (p. 3). Published in the final year of the preceding millennium, Gottfried’s work “After Liberalism” argued that, conceptually speaking, liberalism as a coherent tradition struggles with two problems:

- That it has been denied a specific meaning, and

- That is has taken on a polemical sense which overshadows any previously understood positive denotation.

Many of the political developments deemed unfavorable to today’s American Right have been misattributed to liberalism writ large, when it is in fact more accurate (and conceptually edifying) to regard them as products of a distinct, discrete, political epoch. Proper identification of the liberal tradition is not possible so long as, domestically, there are active rival political organisms each claiming a singular legitimacy. Our failure to make note of such finer details, one which Dr. Haidt has contributed to, remains the leading obstacle to a holistic understanding of the contemporary political scene.

Political and technological crises in the 19th and especially 20th century prompted much debate within liberal circles about the future of their Enlightenment ideology. The emergence of a mass society and all its attendant consequences weighed heavily on the bourgeois liberal elite of old, giving way ultimately to the socialism of mass democracy. The move from bourgeois liberal capitalism to technocratic social democracy (necessitated by the dual challenges of mass and scale, to borrow a phrase from Sam Francis) threatened the integrity of a coherent liberal self-concept, as the liberal societies in which these transformations were occurring suddenly had to contend with a previously unimaginable plurality of desires and demands. Quoting from his book “Leviathan and its Enemies”, Sam Francis is an adroit observer of this phenomenon:

“At the end of the 19th century, liberalism underwent a dramatic reformulation carried out in England by TH Green, JA Hobson, Leonard Hobhouse, and various socialist thinkers in the United States by the writers and activists associated with the progressive movement. The new liberalism of the late 19th century was in many respects, a direct response to the impact of the revolution of mass and scale on the political, economic, and social life of the industrialized societies, and represented an effort to discipline and reform the breakdowns that the revolution caused. The reformulation of liberalism consisted primarily in a retreat from or abandonment of the individualism that characterized bourgeois liberal ideology and a new emphasis on the social and collective nature and duties of human beings.

Since society and its political organ, the state, are in this view prior to the individual, this reformulated version of liberal thought rejected the classical liberal view that restrictions on the activities and functions of the state liberated and assisted the individual”[5]Francis, Samuel T, Fran Griffin, Jerry Woodruff, and Paul Gottfried. 2016. Leviathan & Its Enemies : Mass Organization and Managerial Power in Twentieth-Century America. Arlington, Va: Radix/Washington Summit Publishers. p. 201

The transition was not strictly a matter of ideology, rather, it represented a hyper-stratification of society such that an entirely new elite sphere sprung up, physically displacing those who previously held favor. Quoting again from the same text by Sam Francis,

“There is a combined shift: through changes in the technique of production, the functions of management become more distinctive, more complex, more specialized and more crucial to the whole process of production, thus serving to set off those who perform these functions as a separate group, or class in society; and at the same time, those who formally carried out what functions there were of management, the bourgeoisie themselves withdraw from management, so that the difference in function becomes also a difference in the individuals who carry out the function.”[6]Ibid, p. 112

(Francis, Samuel T, Fran Griffin, Jerry Woodruff, and Paul Gottfried. 2016. Leviathan & Its Enemies : Mass Organization and Managerial Power in Twentieth-Century America. Arlington, Va: Radix/Washington Summit Publishers. p. 201)

These “processes of production” are quite numerous and include, for instance, the process of producing knowledge, art, poetry, and entertainment just as much as they mean flat screen TVs, ballistic missiles, and computer chips. In this way, the managerial revolution (as James Burnham termed it) affected large sectors of the population simultaneously, across the various disciplines and domains of social life. Such a transition could only be considered evolutionary in a metaphorical sense (more will be said on this later).

Ideological (or classical) liberalism should then be understood, borrowing Mosca’s language, as the political formula of a historically contingent entrepreneurial class and the institutions and networks of influence which it once commanded (and to varying degrees and extents, still does). This is the source and origin of our contemporary conservative moral intuitions. Understanding political conservatism as a defeated (or, less hyperbolically, usurped mode of political organization should give us insight into conservatism’s present-day status as the battered and beleaguered housewife of “liberal progressivism” (which we ought to understand as being synonymous with socialism and the mass democratic society).

Consider Haidt’s characterization of contemporary conservative morality in view of the following excerpted passage, taken again from Sam Francis. Do the values of bourgeois entrepreneurial liberals not harmonize with the conservative psychology presented in Haidt’s work? Quoting Peter Berger, Francis shares the following:

“[T]he bourgeois believed in the virtue of work, as against the aristocratic idealization of (genteel) leisure… in Protestant countries it tended toward a style of inconspicuous consumption… The bourgeois emphasized personal responsibility (“conscience”, especially in its Protestant form)… [B]ourgeois culture was individuating at the core of its moral worldview. Also, the bourgeoisie went in for “clean living” both in the literal and the derived moral sense. This theme (epitomized in the maxim that “cleanliness is next to godliness”) carried into the minutia of daily conduct – the manners of dress and speech habits of personal hygiene, the appearance of the home.”[7]Ibid, p. 31

(Francis, Samuel T, Fran Griffin, Jerry Woodruff, and Paul Gottfried. 2016. Leviathan & Its Enemies : Mass Organization and Managerial Power in Twentieth-Century America. Arlington, Va: Radix/Washington Summit Publishers. p. 201)

This competition between “liberal” values (care, fairness, liberty) against “conservative” values (loyalty, authority, sanctity) ought to be understood as resulting from a particular group of elites arising organically and in opposition to the hegemonic order of their time. Entrepreneurial bourgeois capitalism overthrew the old aristocracy just as therapeutic social progressivism has now overthrown the preceding “conservative” political order. While vestigial “psychological conservatism” exists in many places as something cultivated (in the form of mass propaganda) while in others as something of a holdout (a pocket of existential cohesion, as invoked earlier), it should primarily be understood as the downstream consequence of a previous elite’s self-justifying political formulation.

Mass democratic society, or socialism if you prefer, being founded on secular rationalism and a commitment to the scientific view of the world should be understood as the progenitor of progressive liberalism and its overemphasis on the “care”, “liberty”, and “fairness” intuitions. Care, liberty, and fairness, in this sense, are not strictly psychological phenomena but are ideological ones applied in service of the now hegemonic managerial state. Therefore, it is an institutional-structural phenomenon primarily, and not an individual-psychological one singularly. “Progressive liberal morality” is merely the psychological consequence of the political formula we call “socialism”.

I will invoke Sam Francis once more, here, as his depiction of the transition into managerial democracy highlights the historical contingencies responsible for provoking this overemphasis on Haidt’s care, liberty, and fairness intuitions. Quoting Daniel Bell, he says:

“The real social revolution in modern society came in the 1920s when the rise of mass production and high consumption began to transform the life of the middle class itself. In effect the Protestant ethic as a social reality, and a lifestyle for the middle class was replaced by materialistic hedonism in the Puritan temper by a psychological eudaemonism… [T]he claim of the American economic system was that it had introduced abundance, and the nature of abundance is to encourage prodigality rather than prudence. A higher standard of living, not work as an end in itself, then becomes the engine of change. The glorification of plenty, rather than the bending to niggardly nature becomes the justification of the system.”[8]Ibid, p. 34

(Francis, Samuel T, Fran Griffin, Jerry Woodruff, and Paul Gottfried. 2016. Leviathan & Its Enemies : Mass Organization and Managerial Power in Twentieth-Century America. Arlington, Va: Radix/Washington Summit Publishers. p. 201)

A transformative social reality (access to abundant material resources) led to a transformative psychological one (ravenous pursuit of material and egoic desires), of which modern day progressives are merely the beneficiaries. Occurring against the backdrop of an intensely self-scrutinizing liberal discourse, this thumotic surge would be wedded to the equalitarian interpretation of liberal philosophy which, as we can all plainly see, eventually won out. The resulting metaphysical avarice is yet another bit of progressive inheritance. As such, the supposed moral “deficiency” of today’s progressive elites is no deficiency at all, but rather, a mode of self-differentiation. More significantly, it is a means by which they may wage war against – and more fully extirpate – the remnants of the old bourgeois order. Importantly, Francis highlights the natural antagonism between managerial democracy and bourgeois liberalism:

“The managerial elite of the mass corporations thus has a group interest in destroying the individualism and diversity of the bourgeois order through its collective discipline and homogenizing processes. It also subverts the bourgeois work ethic and its derivative values through its promotion of mass hedonism and consumption.”[9]Ibid, p. 35

(Francis, Samuel T, Fran Griffin, Jerry Woodruff, and Paul Gottfried. 2016. Leviathan & Its Enemies : Mass Organization and Managerial Power in Twentieth-Century America. Arlington, Va: Radix/Washington Summit Publishers. p. 201)

Our present-day self-concept as a “liberal democracy” is merely another political formula by which the elites may tether what remains of the preceding regime to that which exists today (neoliberalism, then, may be seen as a synthesis of the bourgeois entrepreneurial order with the contemporary therapeutic-managerial state).

Having explained this supposed psychological difference between modern conservatives and liberals from the point of view of political economy, there yet remains an unaccounted-for element of the mystery. As such, folding a sociobiological view into this managerial revision of the Moral Foundations Theory is prudent, particularly if one seeks to explain the dramatic leftward turn that the United States took following the postwar period (and, especially, in the years since “the Great Awokening”, beginning roughly around the time of the first Obama presidency). Without incorporating this view, we certainly could not understand the extreme partisan morality displayed by progressives over the last two decades.

As Sam Francis has argued, the reach of the managerial revolution has been exponential: technocratically escalating along the dimensions of mass and scale further into populations that were previously not as well represented among prior generations of elites, the 20th century became what has been termed descriptively (and sometimes pejoratively) “the Jewish century”. And while this generation of managerial elites presently looks to be at its nadir, it nonetheless remains well entrenched and capable of significant action. The new political formula, generated specifically for the purposes of postwar governance, represented best among such figures as Leo Strauss, Karl Popper, and Richard Hofstadter (differing in methodologies but always converging in aims) as well as institutions like the ADL (though its origins technically prefigure this new formulation) presented a refortified version of liberalism, Americanism, and the Western canon more broadly, which dogmatically stressed empathetic and equalitarian approaches to political and social problems.

America’s descent into cruel, shrill, racial distortion must be understood as the hideous love child of Gentile equalitarianism and Jewish Machiavellianism. In the years following the second world war, our nation’s superego bent suspiciously in the direction of partisan self-preservation, funneling all moral discourse through an imperceptible filter: Jewish interest. Racial supremacy was re-institutionalized through the veiled language of universal dignity and human rights. Taking again from his book “After Liberalism”, Paul Gottfried is again prescient:

“Behind this rhetoric, however, it is possible to discern other far-reaching projects, some of which this book has outlined. All of them have pertained to a specific form of rule and combined a public charge with generally ill-defined but expanding control. The administrative state, as it advances into its therapeutic phase, has refused to recognize its coercive reach or whatever advantages accrued to it from those tasks it has gladly assumed. By concealing its operation in the language of caring, it has blinded us to the truths enunciated by Cicero, Hobbes, Weber, Schmitt, and other past political analysts. Potestas [power, legal authority], as Cicero explained, is given to increase one’s dignity; it allows one to punish wrongdoers and to exercise magisterial authority, while becoming a means for preserving and securing a greater sufficiency of its own resources.”[10]Gottfried, Paul. 1999. After Liberalism : Mass Democracy in the Managerial State. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p. 141

Far from being some harebrained antisemitic conspiracy, the last eighty or so years have born witness to an unprecedented flourishing of Jewish political privilege inside the United States (see both Samuel G. Freedman’s “Jew vs. Jew: The Struggle for the Soul of American Jewry” and J.J. Goldberg’s “Jewish Power: Inside the American Jewish Establishment”), and with this flourishing (as Gottfried has pointed out) an accrual of advantages. But these “accrued advantages” ultimately are to the detriment of all. Managerial responses to the dual challenges of mass and scale have struggled (and failed) to account for the endless influx of racially alien populations while still maintaining a privileged standing for America’s Jewish citizenry. The untenability of such a prospect has quickly become apparent to all, spurring dramatic change not only in the U.S., but around the world. We are seeing very clearly, thanks to the recent conflict in Gaza, just how badly the managerial regime has degraded and even, how it may fall. We are also seeing the moral and cognitive bankruptcy of its fundamentally downstream psychological consequences, which will surely recede into marginality once the forthcoming political paradigm fully instantiates itself.

We cannot understand the self-loathing psychology of today’s self-avowed liberal man and woman without first appercepting the preeminence of political Judaism throughout America’s most influential institutions. One half technological (the erection of the managerial state) while on the other half sociobiological (the unceasing surge of Jewish political control), so-called “liberal moral psychology” is in fact the byproduct of highly contingent circumstances and is not, as Dr. Haidt has argued, resulted exclusively from individual self-construction.

Conclusion

Trump’s 2016 campaign was, by most accounts, an unforeseeable event. At the very least we must admit that its consequences were rather shocking indeed. What has been interesting to see was the eruption of liberal chauvinism that emerged in response to Donald Trump. An immune response was provoked, resulting in an uninterrupted wave of cultural and political lib-imperialism even more daring and egotistical than what America witnessed during the Obama years (the previous high-water mark of progressive cultural tyranny – one many, including myself, thought impossible to surpass). Trump was the first credible populist candidate in some time, his presence forcing the liberal establishment into a pronounced war footing.

The picture of liberal moral reasoning as seen in the post-Trump era looks markedly different from the one presented by Jonathan Haidt, which to my view only reinforces the necessity for a political critique of his political psychology. A victim of his own ideological commitments, and perhaps as well to a certain self-forgetting of identity, Haidt’s Moral Foundations theory provides us with an incomplete (though nonetheless compelling) account of man’s moral psychology. Psychologically speaking, Haidt’s social intuitionist model – the basis for his MFT – is sound. However it is the predilection for liberal pluralism and an over-reliance on evolutionary thinking which ultimately weighs down his otherwise novel and insightful psychological findings. For all his criticisms, Haidt is nevertheless a victim of Western WEIRD morality, too. Despite his shortcomings, it is as I said in the beginning: Haidt’s publication served as a mighty warning shot. Now, a full decade after its release (and bearing recent events in mind), it is obvious that The Righteous Mind precipitated a revolution of thought which reshaped Conservative politics in America (and, indeed, around the world).

Which brings me to the last remaining thread yet unpulled: the century-long process of social engineering, as executed by the managerial elites, has undoubtedly had a destabilizing effect on the American gene pool. We are already several generations into a process of familial and social planning which selects against illiberalism writ large. While the origins of this revolution were not genetic in a strong sense, American survival will be predicated on genetic and cultural changes in the population which select for strength, courageousness, and self-sufficiency. The civil war will, in the end, be a genetic one.

Notes

[1] Haidt, Jonathan. 2012. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. New York: Vintage Books. p. 341

[2] Haidt, Jonathan. 2012. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. New York: Vintage Books. p. 341

[3] Ibid, p. 10

[4] Ibid, p. 12

[5] Francis, Samuel T, Fran Griffin, Jerry Woodruff, and Paul Gottfried. 2016. Leviathan & Its Enemies : Mass Organization and Managerial Power in Twentieth-Century America. Arlington, Va: Radix/Washington Summit Publishers. p. 201

[6] Ibid, p. 112

[7] Ibid, p. 31

[8] Ibid, p. 34

[9] Ibid, p. 35

[10] Gottfried, Paul. 1999. After Liberalism : Mass Democracy in the Managerial State. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p. 141

RSS

RSS